|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

Glamour (US)

August 1992

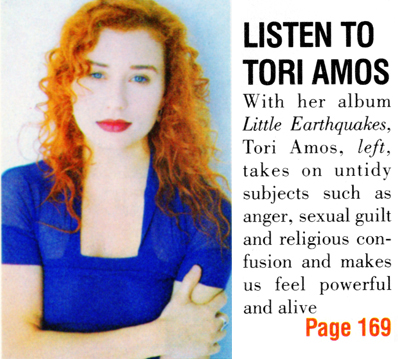

LISTEN TO TORI AMOS

This brave new voice sings about rape and rage. The twist is, she makes us feel sexual, powerful and alive.

By Brook Hersey

"I went to see Thelma & Louise, alone, on a whim," recalls singer-songwriter Tori Amos. "And my life changed. When Susan Sarandon killed the would-be rapist, I breathed for the first time in seven years." Two hours later, Amos, herself the survivor of a harrowing sexual assault, wrote "Me and a Gun." The chilling song, sung a capella, describes the thoughts -- desperate and mundane -- that ran through her head during the attack.

People don't just discover Tori Amos, they become obsessed. In her song "Silent All These Years," she sings, "Sometimes I hear my voice and it's been here/silent all these years." Listeners who've felt unimportant and powerless, who've gone through the emotional struggle for self-worth, seem to feel she is telling their long-overdue story.

With her album Little Earthquakes, the 28-year-old daughter of a Methodist minister from North Carolina stakes out a chunk of musical terrain all her own. Amos skirts the traditional confessional-songwriter preoccupation with love and loss to take on such unntidy subjects as anger, sexual guilt and religious confusion. In "Precious Things," for instance, she remembers being a teenager and seethes about wanting guys who treated her badly: "I wanna smash he faces of those beautiful boys/those Christian boys/so you can make me cum that doesn't make you Jesus."

"Me and a Gun" gets inside the actual moment of rape. The tension between the calculated gentleness of Amos's voice and the visceral horror of the act she's describing says it all about the strange forms that self-preservation takes, about deferring rage in order to survive. "I was kidnapped and sexually violated," says Amos. "You feel like your boundaries have been crossed to such an extent that there is no law anymore, that there is no God. You feel like the mother in you will do anything to protect the child in you from being shredded before your eyes. You're thinking: I gotta get out alive. I gotta get out alive.

"With 'Me and a Gun,' I hope attackers as well as victims are listening. As well as judges as well as lawyers. I want you to taste in the back of your mouth what it was like to be in the car with the pervert."

If Amos's only goal was to vent, it would be tempting to lump her in a catagory with other female artists -- Sinead O'Connor, Tracy Chapman -- who derive their formidable power from singing about anger and pain. What's different about Amos is that she manages to find room in her persona for both outrage and ripe eroticism. Singing and playing piano at New York's Bottom Line on the opening night of her North American tour, she seemed to be issuing a challenge: Wake up and feel. Tossing her flaming hair, she undulated on the front corner of her piano stool, looking like she was approaching orgasm. The effect was an in-your-face sexuality that would have been electrifying even if her music had been mundane.

Amos has opinions on everything from the antichoice movement ("one of the things that makes me saddest now") to both Madonnas (she talks about them both so much that she must distinguish between "Mary the Madonna" and the singer. She's a major fan of the latter, to whom she says, "Madonna, if you ever need a plate of spaghetti, stop by my house"). But she gets most passionate talking about her album's main theme: the painful emotional costs of not recognizing your own needs. "I'm not the kind of woman who takes things sitting down. I wrote 'Silent All These Years' because you can have a big mouth and not be saying anything. I didn't know how to say 'fuck you' to the people who knew every answer about how I should live my life. I would find myself sitting with my hand on a fork [her hand clutches hers violently], and I didn't know why I wanted to go for the jugular of the person across the table. I didn't understand: What buttons is this person pushing in me?"

At age 5, Amos won a scholarship to study piano at a conservatory in Baltimore, but was kicked out at 11. Later, she moved to Los Angeles and plunged into the rock scene, where image was paramount. "I would put my plastic pants on, and my thigh-high boots, and pump my hair up and think I was saying something. But I wasn't." In 1988, she released her first album, Y Kant Tori Read, on which she was backed by a heavy metal band. "Critics ripped the record to shreds," she recalls. "I had my whole self-worth tied up in what I did. I was 24 and asking: Where do I stand with myself?"

For Amos, the essential struggle was to accept herself. "I started finding the people inside me. The ingenue. The prostitute that's really angry because I judge her so harshly. The bad girl. She's pretty neat. The self-righteous virgin who knows everything about sex and has never made love. The fearful mother -- the one I had no respect for. The resilient mother -- I love her."

If the Little Earthquakes album were boiled down to a mantra, it would be the last words of the title track: "Give me life, give me pain, give me myself again." She's issuing this challenge to hersef -- not to a god or a boyfriend. For this reason, these words are not whiny but triumphant.

[scans by Sakre Heinze, edited by Richard Handal]

[transcribed by jason/yessaid]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|