|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

Keyboard (US)

September 1992

Tori! Tori! Tori!

by Greg Rule

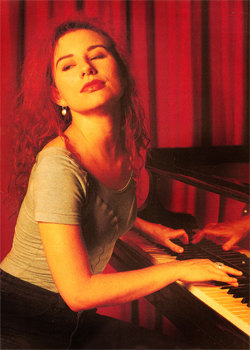

photography by Jay Blakesberg

Armed with provocative songs, a haunting voice, and an approach to the piano that got her kicked out of music school, Tori Amos launches a sneak attack on the pop charts.

Saturday evening, downtown San Francisco. Tori Amos has 600 fans nailed stiff to their seats. Alone center-stage, she slings a mane of red hair and writhes masterfully toward a double-encore climax. Tonight there are no glitzy costumes. No fancy effects. Not even a backup band. Just one woman, one piano, and a solitary shaft of white light. This is music at its stripped-down, unpretentious best. It proudly raises a rigid, irreverent finger to inhibition. It minces no words, and it leaves few emotional stones unturned. From a whisper-soft, breathy sigh to a full-throated punch, it spring boards from one dynamic extreme to the next.

Comparisons to Kate Bush and Laura Nyro are inevitable. Tori's introspective lyrics and sultry melodies conjure images of each illustrious predecessor; her voice, in particular, is hauntingly reminiscent of Bush's. But don't accuse this artist of following too closely in the footsteps of others. Little Earthquakes, her breakthrough release on Atlantic Records, cuts its own wonderfully distinct musical path.

Despite its anti-formulaic (and shockingly blunt) nature, the record has found widespread acceptance. Tori laughingly theorizes, "I think it's my hair color. People like red hair. And another thing is David Lynch, he's the same way. I'm embraced in certain areas: The press, television, and radio in the U.K. have been really supportive. But they don't have format hang-ups. In America there's this radio thing of 'Where do they fit? Tori, we don't know where she fits.'" Perhaps the only fit Tori needs worry about is the one her fans are having over her.

Backstage, after her San Francisco appearance, she disappears into a herd of enthusiastic admirers - signing autographs, posing for group snapshots, and fielding a barrage of questions. With pens and posters in hand, dozens more wait patiently outside the backstage door. Tori, against her concerned manager's wishes, charges happily into the crowd.

All this after a sunrise flight, three interviews, two photo shoots, a sound-check, and a sold-out performance. Next stop, San Diego. The early bird flight, no doubt.

Our day with Tori began with a cab ride through the downtown business district and a stopover at a renowned North Beach Italian eatery. There, over seafood pasta and wine, the outspoken artist let loose on a variety of issues. The first was integrity. "The whole music industry is so much dictated by radio, and who are they dictated by? Advertisers. It's a vicious cycle. And where does it stop?" She was getting visibly riled. "When will musicians stand up and say, 'It's not about being lucky enough to get scraps off the table.' It's not about, We're so lucky that you've given us a chance,' or, 'We'll do anything if you just let us play our music, you o masterful God, you.' Most of us are afraid to listen to our true voices because, 'What if we get dropped?' Well, so what if we do?!'

Every head in the restaurant turned as Tori slammed a clenched fist on the table. But she didn't seem to mind. The topic smacked painfully close to home. Just four years ago she experienced a major failure at the hand of poor guidance - a rock record called Y Kant Tori Read that dove straight to the bottom of the ratings bucket. A record that, in retrospect, she probably shouldn't have attempted.

But the now-28-year-old musician was resilient, battling a couple of years of mental upheaval before re-evaluating her direction and, ultimately, rediscovering her guiding fight - the piano. "I finally brought myself to my knees and said, 'Wait a minute, when I was four years old, I didn't care what anybody thought.' There were no doubts about, 'Am I going to be successful?' I mean, I'd get my Shredded Wheat in the morning and play the piano and that was successful! I didn't think about people clapping. I didn't think about whether or not they liked it, and needing that from them. I trusted it. I know too many people who started off with these ideas but never followed them through because someone, at some point along the way, said, 'That's worthless'. There's a fine line between listening to everything and listening to nothing."

We Listened to Tori, bug-eyed for two nearly two hours, as she recounted a series of colorful experiences. At times she fought to hold back tears, and, at others, vented frustration and anger. Through it all, though, she exuded a tremendous sense of warmth, compassion, and optimism - laughing and giggling openly, and often.

ON FAILURE

After listening to Little Earthquakes, many readers will find your escapades in the rock world hard to believe. We understand you don't like to talk about it much, but we're curious to know what role that experience played in your artistic development.

The band was together for about two years. We rehearsed three times a week and only played one gig. That's all we did - we stayed in the rehearsal studio, made a tape, got signed, and split up. As a writer, I didn't know what I wanted to express, really, at that point. I can say this now - I couldn't say it then - that I wasn't doing it for the love of music. I was doing it because I had something to prove to the boys who trashed me when I was 13. "We're not looking for this." "It's dated." "Do dance music." "Get a rock band." And after six years of rejection, I started listening to them. The positive thing is, I play the piano much differently today because of that experience. I led myself to believe that, because I'd been playing the piano since I was two-and-a-half, I could play anything. But that didn't mean that I was any good at it. That didn't mean it was coming from here [she points to her stomach]. If it's not coming from here, you smell it. There's nothing worse than seeing a kid play dress-up just to please Aunt Louise. It's awful if they don't do it because they want to do it. At that point in my life I was on auto-pilot. My self-worth was all wrapped up in whether or not this thing was a success. I didn't really consider the girl in all of this. I didn't understand that I was a girl until four years ago. I was just a musician who became very needy. That's the hardest thing with musicians, I think, is that we're so sensitive. We start listening to other people. How much can you take before you start asking yourself, "Maybe they're right?" How many years can you take it? Seven? Twenty? Two? You lose faith in what you're doing.

Did you honestly feel, when doing the rock thing, that you were on the right track?

You bet I did. I wouldn't talk to you about "Me and a Gun" [from Little Earthquakes, the haunting revelations of a rape victim]. As far as I was concerned it didn't exist. And if you Wanted to talk to me about my Christian guilt, I would tell you I had none. I was adamant about what I was doing. I was defending it with every cell in my body. And I wasn't going to expose the part of me that could get cut up. What I didn't realize was that I wasn't immune to getting cut up, no matter which part of me I was showing.

The big one for me was when I started to need the approval of my peers. I think when you grow up and you get used to people applauding you, well, when the applause dies down, that's when you notice. It was, "What am I doing wrong?" instead of, "Maybe they're not getting it, so what?" And this festered for so long, and it became more desperate. " I'll try anything to get that back." You can't put a Band-Aid over open-heart surgery, you know. And while this infection festered, I put Band-Aids over it because I refused to accept that, "No, there's another plan for you."

This story for somebody might be, "Jesus, girl, get over it. There are real problems in life." Well, for me, that was my tragedy. A death of anybody close to me was nothing like that, because I had a part of me that was getting beaten in the corner; that expressive side was degraded, was forced to do things, was not loved. I'm a very cruel jailer. And I was. So when Y Kant Tori Read came skipping down my way, it was just the final thing of many, many, many things that I had done that ultimately got me back to the piano where I could lay myself bare. That record wasn't about "Was it a good record?" or "Was it a bad record?" It was the final thing that made me realize I had to do music for the mere expression of it. It didn't matter if anybody listened. It taught me to not be afraid of exposing myself. And if people wanted to piss all over it, then I'd just let it drip off the tape.

THE CHILD PRODIGY

My mother says I was playing at two-and-a-half. In fact, my earliest memories of life are of me playing. There was an incredible sense of pull and draw. That was my friend. That was my best friend in the world. That was the only thing that understood me and that I understood. I remember having an incredible understanding of the universe. I didn't have fears. I believed that there were monsters. It didn't bother me. They were just part of the room. They weren't a bad thing. I believed in other dimensions. And it wasn't just a Christian world to me. I felt good vibes from Jesus, but I also felt good vibes from Robert Plant. When you're young, you're being told what to think. But I'd go to the piano and that's where I was comforted. It was my protector, the protector of my thoughts.

Did you study piano formally at that age?

I entered Baltimore's Peabody Conservatory when I was five, and the idea was to become a classical pianist because what are you going to do when you can play like that? So the conservatory was downtown where there were real musicians. 'Wouldn't it be great for her to be around real musicians instead of just going to first grade?' You're five, and you think you're going to be around older people. It's a very exciting prospect.

How did you feel about your gift back then?

I knew I was different. I knew I did things that other kids didn't do. But, you know, you don't have an ego when you're five. I didn't want them to treat me like I was weird or special. It would be really great if other people did what I did and we could just hang out. You just want to have friends and play and eat popcorn together. And life is very simple. You get inspired, it's very exciting. It's not about, "When Debbie was your age, she was three months ahead of you."

I was an ear person. And it was the way they taught me that was the mistake. They started me with "Hot Cross Buns." When you go from Gershwin to "Hot Cross Buns" it's a bit of a shock. You don't understand that this is for your good. "How could it possibly be for my good?" There's nothing that you could have said to that girl to convince her. She had no desire to do that. "I play because I love to play." You think you're being punished.

What I really learned from the Peabody came from my classmates. I got the music through them. I understood that there was a Jim Morrison and I understood that there was a John Lennon. They spoke to me like I was an adult. Here I was with my little curls, my feet that didn't touch the floor, and we're all sitting in theory class. And I'm turning around going, "Wow, he's really cute, and he's black, and he has long hair. Can I go home with him?' [Laughs]

By eight, the bottom started falling out. They were looking for improvement and I wasn't improving. "What's she doing?" I was going home and Listening to Beatles records and anything else I could get my hands on. I studied 30 minutes during the whole week of what I was supposed to. It was, "I'm here, and they don't get it, and that's the way it is." You just do that as a kid. You can't say, "Hey, let's have a conference." I was out by the time I was 11, because I was developing my own music all this time.

At 13, my father saw me wasting away, some of my friends were getting pregnant, and he didn't want that to happen to me. So he tried to find a special interest to keep my hands busy, I guess. He said, "Your music was so much a part of your life. Why don't you go back to the Peabody?" So I actually auditioned to get back in. These girls were auditioning for the voice school, singing Ave Maria. Me, I sang "I've Been Cheated" [laughs]. They didn't clap, and they certainly didn't let me back in. So I started played clubs and turning in my songs. I heard something a few months ago from a period when I was 13 to 17, and some of it was so exciting. I'd forgotten. They're a bit more progressive, honestly, than what I do now. I hadn't been diluted yet.

I'd be proud to play you some of that stuff, especially when I was 16. Real exciting changes, no traditional choruses like you hear today out of my work. At that time it was completely about self-expression. It wasn't about, "What will they think?" What happens to a musician is that you either become a teacher, you become a church organist, you do your own music, or you play somebody else's in a lobby somewhere...

Which you did plenty of...

Oh yeah, I wasn't going to be a teacher.

THE PIANO

I wrap my arms around the piano and embrace it. I see the piano as a living being. When I went back to it - after having my little explorations through the swamps and forests, and picking up a few bug bites along the way - I brought back new things. I brought back a new rhythmic sensibility and an overall sense of awareness. Playing all those Gershwin tunes in lobbies taught me what not to do. It really freed me up. I feel like the piano hasn't been explored to its full potential. I'm not talking about synthesizers either. I mean really working with the acoustic instrument. I started to approach it as something that has its own consciousness. It thinks. We collaborate together. It's not like master and servant. At times - and we're all guilty of this - you start whipping your instrument. Domination. Not that I don't like domination. But when it comes to the piano, it's not going to work unless there's give and take.

I've never considered myself to be a great player. I'm just a really creative player - voicings and all that stuff. I play from here [pointing to her stomach]. I've never had the chops like the killers. You know, you walk in and see the killers playing Chopin and yadda, yadda, yadda, and you just go, "I'm impressed." And, to some extent, it is impressive. But from a very different place. Some of them play from their stomach and have the technique. But not a lot of them. Back in school, I would always say, "How do you know that Debussy meant this? Because I certainly don't think Jesus meant this when he said such and such." When people talk about interpretation of a piece, I completely lose it, because again, it's that intuitive place of respecting the instrument and respecting the song. Music, it has an opinion. But yet because I'm different than you, I have every right to play "Claire de lune" my way, as do you. Why should you play it like me? Maybe you're coming from a different background with a different edge that brings it a different perspective. I don't believe for one minute that Debussy would not want to hear your perspective! I don't believe that. I'd love to hear someone's perspective on one of my tunes.

There's no doubt, though, that the classical influence has seeped into my brain, obviously. But [at the conservatory] people weren't encouraged to think for themselves. That's what we're missing. And not just in music - how to be your own thinker. Give the kids tools, so they can go build their own houses; not the blueprint of what the house should be. Getting back to the piano, though, there's a certain respect that I have to approach it with now. If you're not careful, you tend to approach your instrument very lazily. As I play alone at the piano, I have to honor it. I have to know that it is speaking, too. Every night It shows me something different about the song I played a hundred times before. I never play a song the same way twice, like a lot of people do. It also gives the impression that it's a very passive instrument when you think of a singer/songwriter at the piano, besides someone like Jerry Lee Lewis.

But if you're not in the band scene, you don't get the same power or electric feeling that you do from guitars or drums. I see the piano as a real powerhouse instrument, and it can be very edgy. I feel this vibe from it. It speaks to me all the time. That's where the line "There are pieces of me you've never seen" [from the song "Tear in Your Hand"] comes from. That's the essence of what piano is. The piano is a living essence. "All they think all I'm good for is a nice black dress." So I'm starting to explore different things with it.

For the next record, I want to work with this instrument exclusively, not synths with it, but the acoustic piano alone. It could be percussive, or it could be orchestral, maybe it could have effects. There might be solos. I'm out of the way to respect the fact that you're not the only one who's finally claiming that this is my instrument. Because I can hear what it is saying to me, I have a responsibility to listen to what it's saying to me. And now it says, "I have some really good ideas and you're a human, and you could take them down for me - if you can get your own stuff got ideas." I've really become very close to it now.

ON SONGWRITING

I could tell you any load of rubbish about the way I write. The truth is, I really don't know. Each song [from Little Earthquakes] came together in a completely different way. What I can say is that, generally, when I'm writing, things start to flow. But still I have to craft it. It's like I have this hunk of clay in my stomach that I'm conceiving. And it's telling me what it wants to be. But I have to put it into a language. I hear it in my head and in my stomach, but the key is translating it into feelings and words. You can taste something, but try and put that taste into words. You have to bring in forms of reference. If you've never had a papaya, well, it's kind of like such and such, instead of actually experiencing the papaya. With this record, a song like "Silent All These Years" has a certain story line going on musically that's really the antithesis of what's going on verbally. It's counterpoint, pure and simple. But instead of French horns and cellos or something, it's words and music. And I find it very exciting when an acoustic instrument has its knife out. It can take on these different roles. The idea of being a woman ... you come over to my house and I'm serving a fruit plate. That's not always going to happen. Especially if somebody isn't being polite, or if somebody's being a dick. Then I'm going to put the peelings on the floor and watch you trip, and giggle. And that's the same with the acoustic instrument. It's not always just about, "I'm vulnerable, I'm sad." There are many different sides, and the beauty comes in exploring them.

He [pointing to co-producer Eric Rosse, across the table] was there when some of the songs were being written. "Mother" was written at 6:30, 7:00 in the morning. We were on a futon in the little place I had at the time in Hollywood, and I got up really early and started meandering on the piano. I meandered for about 25 minutes and I started to get this ... [hums the intro to "Mother"] ... and I hear this voice from the futon, "What's that!" And I said, "Oh, it's shit. Forget about it." And he yells, "Play it again!" What happens with each one is that there will be a word that comes with the melody. Then a bridge section will start to work and I'll know it wants to be there. And then maybe I can't figure anything else out so I'll put it aside. Three months later, I'm walking down the street and I'll come up with four notes, and that's what I'm going to build the next section on.

Do you write your ideas down on paper before putting them aside?

Well, I'm not very good at writing things down sometimes. Maybe it'll be on the back of an envelope, a bill, a magazine, or I might record it on a ghetto blaster.

Do you ever wake up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat and run to the piano with an idea?

Hot sweat, yeah. Sometimes. But then there are times when I'll have the greatest ideas and I wake up in bed and I just go, "I'm too tired." Then I forget. But besides all this intuitive stuff, you train yourself on what works and how it works. And again, it goes back to that belly thermometer. If you learn to accept the first thing that comes to you, then you can't be objective. I listen to a lot of music and I read a lot of books and I know something great when I hear it. It just has a level of greatness and you know it. I can argue almost anytime why it is and isn't. But I can't tell you why it works. All I can do is just throw my hands up in the air. And it doesn't matter whether it's up my street or not. I can acknowledge it if it works. Again, it's that thing in your belly. You know when the jam isn't happening. You know when it's too runny. And if somebody says, "Well, some people like runny jam," well fine.

Anyway, with my own stuff, I know when it's not happening because I have pains in my stomach when it's not. I guess I'm real lucky for that. When a mix is up and I have to run to the toilet, there need to be no words said. You can't just walk out of the studio because you're ill. And I think that when you have so much love for it, it just affects you like that. The other thing is, I'll go, "I'm going to write four different bridges for this song and we'll see who wins the prize." And then it's like, "What if I change this chorus? What if I just cut it in half?"

That all happens sometimes. You can't be afraid - and I used to be - of experimenting. "Boy, I can never come back to that?" But that's saying, "I don't have it yet." We always want to be able to just get it, I was able to get to the place on this record where it was okay if I didn't have it yet. I'd walk around with these songs stalking me. We'd be going out to a movie and I'd start jittering. The songs themselves, they want to be something. I would just open myself up to reading things, and it would show me that I didn't have to say 'I'm leaving' by saying "I'm leaving." That's what watching a lot of movies does for me. I see how the camera angle goes. I see how the lighting is. How did they get this across? You know, write like you're a camera. The other big thing is keeping my musical vocabulary up. "Why do I always go to this change?"

It gets to be habit. Your ears get so used to, "I want it to resolve here." A string arranger once said to me, "You can't do this. You can't go here." And I went, "Who said that? Who made up that rule? And what grave is he in over in Europe? Who cares? The worms have eaten him. It's over." And that's where the vision gets lost. But you have to know when it's working or not. And I know when it works. It's really great. I'm so glad I do [laughs]. And when it doesn't, it's unacceptable to let it fly. Even if that tune never gets out

Running short on time, we shut off the tape recorder and headed toward the venue for a pending photo shoot and soundcheck. On the way out of the restaurant, we asked Tori one final question:

Were there any compromises on Little Earthquakes?"

Songwriting-wise, there were no compromises, absolutely none. Every note and every lyric - none. It always comes down to, "Could the hi-hat have been this, or whatever?" There's always 100,000 choices. "Did I want this effect on my voice?" I go through those things. But hey, they are what they are. This record is what it is. You've gotta stop somewhere. You've got to cut the string.

Co-producer Eric Rosse

The three lives of Little Earthquakes

"The record was essentially done in three phases," says co-producer Eric Rosse of Little Earthquakes. The first batch of tracks ["Crucify," "Silent All These Years," "Winter," "Happy Phantom," "Leather," and "Mother"] were cut at Capitol Records in Los Angeles with Davitt Sigerson producing. "The piano and vocal tracks were recorded first, and then everything else was built around them." A 40-plus piece of orchestra added layers of sweetening under the skillful guidance of arranger/conductor Nick DeCaro.

After hearing the first group of songs, the record company, surprisingly, balked. "They sort of pulled a Linda Blair," recalls Eric. "They came back and said, 'What's this?' to this beautiful work." So Eric and Tori disappeared into Eric's home studio for phase two, which yielded the songs "Girl," "Precious Things," "Tear In Your Hand," and "Little Earthquakes." "It was the buck-and-a-half phase where money was really, really limited," laughs Eric. "Everything was pretty much done by the skin of our teeth. We used my old 3M 24-track analog machine, a decent commando-style Allen & Heath board, and a Yamaha CP-80 piano. We also went outside to a little place called Stag Studios, where they had a nice Yamaha grand."

For phase three, Tori jetted to England where she recorded several B-sides and the songs "China" and "Me and a Gun" (produced by Ian Stanley). During those sessions, Tori surprised her team of collegues with an impromptu performance. Eric recalls, "One of the B-side cuts came together on the spur of the moment. It was a tune called 'Thoughts' and she wrote it as the tape was running, literally. We were getting sounds while she was doodling on the piano and I said, 'What's that?' So we just hit record and she wrote it in one pass."

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|