|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

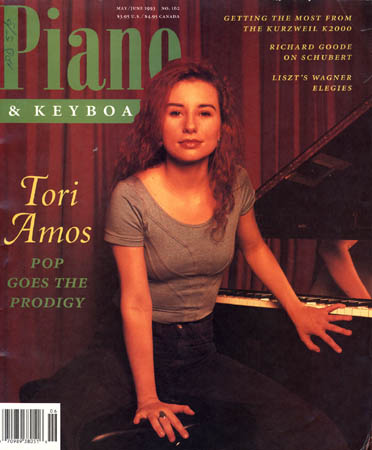

Piano & Keyboard (US)

May/June 1993

Pop Goes the Prodigy

Tori Amos finds acceptance

By Melanie Haiken

"Musicians are like puppies. They just want to be loved," muses Tori Amos, choosing her words slowly and deliberately. "But it's really important that, as musicians, we remember that nobody can give us love -- it'll never be enough. We have to do that." She pauses, as if anticipating a challenge. "If we didn't love to share, we wouldn't be out there. We do need to share. But if we're desperate, then we never explore our full potential because we're always looking around asking 'Well, what do you think? Was it okay?'

"You're asking some tone-deaf person, 'What do you think?'" she says, with an ironic laugh. "At a certain point you have to ask, 'Well, what do I think?'"

What Tori Amos, piano prodigy turned pop star, thinks -- and how she thinks -- is explored and communicated with searchlight intensity in her recordings and performances. Her 1992 album Little Earthquakes, a collection of 12 songs that examine with astonishing honest topics as intimate as sex, family relationships, rape, and the painful process of self-acceptance, has quietly sold more than 500,000 copies -- making it certified gold and Amos a genuine word-of-mouth star. Since then she has also released an EP, Crucify, which includes covers of such unpianistic choices as Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit" and the Rolling Stones' "Angie." But it is not just her records that have people talking about Tori Amos; her live shows have sold out across the country as word spreads about this 29-year-old redhead who can hold an audience's rapt attention with just a microphone and a grand piano.

During a concert at San Francisco's Palace of Fine Arts Theater, Amos swivels her body to face the audience, her eyes almost never looking toward the nine-foot Steinway, where her hands slide and flicker over the keys. With one long, bell-bottomed leg planted on either side of the piano bench, Amos grinds her hips suggestively as her feet, in strappy, spike-heeled shoes, rock along with the music.

"Mother the car is here / somebody leave the light on / green limousine for the redhead dancing girl. . . somebody leave the light on / just in case I like the dancing / I can remember where I come from . . ." she sings, in a voice that slips from a feathery whisper to a sultry alto. Her hands command the keyboard with forceful fluency, offering up great crashing chords, slithering runs, and whispy tremolos. Her extensive stylistic vocabulary ranges from rollicking vaudeville rhythms, used to great effect in the salacious "Leather" and the sardonic "Happy Phantom," to lush, evocative melodies rich with chordal harmony, as in the memory-laden "Winter" and "Mother." Watching Tori Amos play, it is easy to believe that, as she reports, she has been playing the piano since she was two-and-a-half years old.

A bona fide child prodigy, North Carolina-born Myra Ellen Amos (she herself selected the name of Tori later on) won a scholarship to the Peabody Conservatory at the ripe old age of five. There she studied the classics alongside students more than twice her age, but found herself more intrigued by the Beatles, the Doors, Jimi Hendrix -- and by her own budding compositions, "because I was bored with what everyone else was writing." She was thrown out of Peabody at age 11 for putting her considerable talents at the service of improvisation rather than interpretation. She recalls how she began the all-important swing in this direction by way of an imaginary exchange with her favorite composer, Bela Bartok: "He's talking to me and I want to talk back. So I'd play a little of him and then I'd go, 'Hey, Bela, check this out,' da-da-da-da, and he'd go, 'Hey, Tori, check this out,' and I'd go, 'Yeah, that's cool,' and we'd have this conversation and we'd answer each other through out musical composition. Who's to say that that wasn't real? It was real to me. He inspired me to look inside myself -- do I have something to express?"

A bona fide child prodigy, North Carolina-born Myra Ellen Amos (she herself selected the name of Tori later on) won a scholarship to the Peabody Conservatory at the ripe old age of five. There she studied the classics alongside students more than twice her age, but found herself more intrigued by the Beatles, the Doors, Jimi Hendrix -- and by her own budding compositions, "because I was bored with what everyone else was writing." She was thrown out of Peabody at age 11 for putting her considerable talents at the service of improvisation rather than interpretation. She recalls how she began the all-important swing in this direction by way of an imaginary exchange with her favorite composer, Bela Bartok: "He's talking to me and I want to talk back. So I'd play a little of him and then I'd go, 'Hey, Bela, check this out,' da-da-da-da, and he'd go, 'Hey, Tori, check this out,' and I'd go, 'Yeah, that's cool,' and we'd have this conversation and we'd answer each other through out musical composition. Who's to say that that wasn't real? It was real to me. He inspired me to look inside myself -- do I have something to express?"

Amos, who lives in London, is speaking by telephone from the Los Angeles offices of Atlantic Records. She is in town for an appearance on Jay Leno's Tonight Show, topping off a grueling 14 months of touring in support of Little Earthquakes. Despite the fact that she was up until the wee hours the night before, Amos is jaunty and warm and seems eager to talk.

"Some pianists don't want to improvise," she continues. "They become masters at expressing somebody else's compositions. And I respect that. It's just that it's somebody else's words -- you know, musical words -- and I don't want to just keep repeating."

Two years after being expelled from Peabody, Amos auditioned to be re-admitted and was rejected. Although it is clear that the experience was traumatic, Amos does not express any regrets about the years of rigorous training at the piano bench: "It's like my friends that studied to be ballerinas . . . their bodies are trained. The way they sit, the way they move, is an integral part of their being. They don't even think about it. It's part of their movement now. Being trained the way I was trained, I don't think about it, it's just the way I hear things. Because Bartok was such a hero of mine, I think differently. My chord vocabulary is different than a jazz player's. One isn't better than the other; they're just different, very different."

Just two weeks after she failed to get back into Peabody, Amos had an experience she sees as pivotal in shaping her love for live performance. She got her first gig at a gay piano bar in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Although Amos' father is a minister, as were both of his parents, and she describes that side of the family as "not exactly free thinkers," Amos was only 13 and required a chaperone. She has vivid memories of her father standing in the back of the bar -- wearing his clerical collar -- proudly watching her play. Amos continued playing bar gigs in the D.C. area throughout her high school years, and the experience is evident in her concert showmanship.

"Playing in a bar makes you become very much a one-take person. The experience teaches you that if you weren't present on that tune, you can't go back and get it, you have to let it go and move on to the next tune. It's very good for putting you in the moment. You're not six songs from now, you're not two songs back, you're in this measure and you're singing this note and you're in this phrase. You have to live in this phrase. Some people make love and they're deciding what they're going to wear the next day. Well, it's like maybe you should be singing the song."

At 21 Amos headed west to Los Angeles, where she tried out a smorgasbord of pop and hard-rock incarnations in search of fame and fortune. In 1988 she released a heavy-metal-style album, Y Kant Tori Read, on which she played synthesizer. An abysmal failure, it sent Amos into a tailspin of insecurity and forced her to rethink her relationship with the piano.

"I felt so intertwined with it that I had no identity except the girl at the piano," Amos says. "And I didn't respect it anymore, mainly because I wanted this piano to make me worth something. I wanted it to bring me friends and recognition. I guess it's like any job you do -- you think it's going to give you a sense of yourself. Well, I didn't get any recognition, so I felt that I had failed it and that it had failed me. It was very much a relationship. I had to leave the piano for awhile until I could approach it as an instrument, not as a tool to make me feel like I had bitchin' friends." The failure of her first record sent Amos back into herself in search of inspiration. She rented a piano and holed up with it, healing herself with the songwriting process.

The healing helped Amos find her voice, both musically and lyrically, a reawakening she celebrates in many of the songs on Little Earthquakes. "Sometimes I hear my voice and it's been here, silent all these years," she sings, a note of pleased surprise in her voice. That voice is in actuality a multitude of voices. A hallmark of Amos' songs is the sudden juxtaposition of a vast arsenal of styles. A slowed-down stride bass line suddenly lifts into lacy filigrees of melody; a splashy show-tune riff, spiky and syncopated, careens -- albeit with sure-handed control -- into a hushed ostinato. In "Winter," a song filled with remembrances of her childhood relationship with her father, his words blend with her own in the mantra-like refrain: "When you gonna make up your mind? / When you gonna love you as much as I do," an exhortation to self-acceptance over waves of counterpoint.

The healing helped Amos find her voice, both musically and lyrically, a reawakening she celebrates in many of the songs on Little Earthquakes. "Sometimes I hear my voice and it's been here, silent all these years," she sings, a note of pleased surprise in her voice. That voice is in actuality a multitude of voices. A hallmark of Amos' songs is the sudden juxtaposition of a vast arsenal of styles. A slowed-down stride bass line suddenly lifts into lacy filigrees of melody; a splashy show-tune riff, spiky and syncopated, careens -- albeit with sure-handed control -- into a hushed ostinato. In "Winter," a song filled with remembrances of her childhood relationship with her father, his words blend with her own in the mantra-like refrain: "When you gonna make up your mind? / When you gonna love you as much as I do," an exhortation to self-acceptance over waves of counterpoint.

"It's been four years of working toward the point where I'm enough for myself just because I accept who this girl is," Amos says. "And that's the way I had to be before I could approach the piano as an equal and not use it. Before, I was really using it the way you would use your last name or who your father was -- or whatever you use to feel powerful. But you feel powerful because you're enough for yourself, just because you're this person. And that's where I had to get before I could play again. And it's something I have to work at every day."

Today, pianos follow Tori Amos wherever she goes; the Bosendorfer firm recently signed her as one of their artists. "This is a new direction for us," comments Vince Cooke, Bosendorfer's concert artist coordinator. "Tori is a unique individual. She is very particular about her pianos because she believes the piano is an extension of herself onstage. We're very happy to work with someone who cares so much about pianos."

Amos can barely contain her excitement at the prospect of playing what she calls, "the best pianos in the world" in her concerts and at home. "The reason I love to play Bosendorfers is because I think their whole [manufacturing] process is trying to keep them as unmechanical -- as un-factoryized -- as possible, so that the soul of everybody who touches one of works with it is in there." She was moved by the handcrafting processes she witnessed during a recent visit to the Bosendorfer factory in Vienna. "A piano is alive because of all the feelings the men working on it put into it," Amos explains. "A technician told me if he is angry -- if he has had a fight with his lover or if he is not feeling good -- the piano will carry that with is. It will hit harder. Or it won't hit hard enough if he is feeling insecure. The sanders have pictures of naked women in the room because when they touch the piano they want her to feel like a woman's body."

Amos often returns to her concept of the piano as a living being, to be communicated with as a friend and confidant. She tells of being very upset one day in New York just hours before she had to go onstage and then going to the Bosendorfer showroom. "They left me alone in the room with 30 pianos, and I felt that the piano spirits came and wrapped their arms around me. I wept and wept and wept alone with them. And they hugged me and I walked out and I had to do a show in two hours. And I felt like they understood."

Her relationship with the piano extends to her concern for the condition of the instrument she plays. The hardest thing about the 200-plus nights she has spent performing on whatever was available, Amos says, was having to play pianos that hadn't been treated well. "You're really dependent upon what the instrument can do. If it doesn't have a strong action in it -- 'mushy peas' is what I call it -- then you cannot do much with it. You're clumsy, you don't have an attack, you can't play fast because you're just tripping over your hands."

It's not only the piano that Amos feels she has a relationship with: she also values her connection with the technicians who maintain the instruments. Good technicians make a difference "because their whole being gets put into the piano. And if you wouldn't want to sit down and have a drink with them, why are you going to crawl all over their pianos?"

Amos will be crawling all over a lot of pianos in the years to come. She is currently crafting songs for her next album, which she plans to record in Taos, New Mexico, using a nine-foot Bosendorfer model 275 that she herself selected from the factory showroom. Amos hopes to release the album in early 1994 -- "I'm a winter girl; I like coming out when things are desolate and everybody is ready to slit their wrists." Although her live shows will continue to revolve around the solo acoustic instrument, the new album, like Little Earthquakes, will showcase her talents on synthesizer and sampler as well. "Orchestration's really exciting to me when it's done well. It excites me to bridge acoustic and electric music the way Jimmy Page did, but with the piano instead of the guitar," Amos says, refering to the Led Zeppelin guitarist by immortalized by his famous solo on "Stairway to Heaven."

Even on the road, Amos spends several hours a day at the piano, experimenting with new songs. "I'll work on bass patterns and then solo patterns and the I'll change them around because I hate half of them. It's just constantly discovering, when can I do with this chord, how many ways can I play it? Maybe I'll discover something in the first ten seconds and then nothing in the next two hours, and I really should have stopped after the first ten seconds and had a peanut butter and jelly sandwich."

Yet despite the importance improvising has in her compositional process, Amos does not leave room for it in her songs once they are written. "Phrasing-wise, there is room to improvise, but the notes are the notes and I don't change them. That's like giving your kid a face lift," she laughs. "Just go make another kid -- with a different father maybe."

As she speaks enthusiastically about going on tour again, it's obvious that Amos genuinely loves to perform. While many musicians see larger halls as a mark of success, Amos prefers more intimate venues. "It's like doing it in the bedroom is going to be more comfortable than doing it on the butcher block in the kitchen," she says. "There's just no way around that one."

After years of riding the roller coaster in search of rock 'n' roll glory, Amos is emphatic about the necessity of being true to one's own inner musical vision, whatever that vision encompasses. She seems to have made peace with the disparate musical experiences that conspired to produce a Tori Amos, and she embraces the variety of available musical paths. "It's really what moves you," she says. "There's no right and wrong, because the guys and girls who love jazz, you feel love when you hear it. And the ones who love classical, you feel love when you hear it. And the ones who love atonal music, you feel their respect for it. And that's what's exciting, when somebody honors and loves their musical vocabulary and is exploring it."

What matters in all these areas, Amos stresses, is the need for musical integrity. "At some point it is not about, are they good or not? That's like asking, is Meryl Streep good? At a certain point you move beyond good or bad and it becomes just exploration. It might move you or it might not move you, but that doesn't mean it's invalid. And that's what's important for musicians to remember -- at a certain level, you either are moved or are not moved. End of sentence, end of story."

[thanks to richard handal for providing scans of this article]

[transcribed by jason/yessaid]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|