|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

Los Angeles Times (US)

Calendar, page 53

January 30, 1994

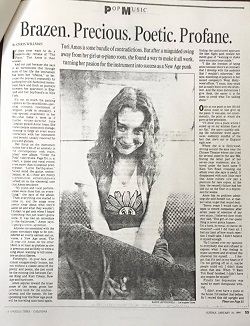

Brazen. Precious. Poetic. Profane.

Tori Amos is some bundle of contradictions. But after a misguided swing away from her girl-at-a-piano roots, she found a way to make it all work, turning her passion for the instrument into success as a New Age punk

By Chris Willman, a frequent contributor to Calendar.

If they ever want to do a modern-day remake of The Piano, Tori Amos is their woman.

And not just because she says in all earnestness that through most of her life the instrument has been her "lifeline," or because she proves it repeatedly by packing her old-fashioned instrument back and forth on journeys between her apartment in England and her boyfriend's in New York.

It's not so much the packing logistics as the sensibilities -- personal intensity, resentment of religion, pride in sexuality, a near-spousal attachment to her 88s -- that make it seem as if maybe writer-director Jane Campion picked Amos' brain. She scares people sometimes onstage, seeming to forge an overt erotic connection with her instrument (and bench) usually reserved for guys and guitars.

Her focus on the instrument makes her a bit of an anomaly in the contemporary rock realm. Amos' new album, "Under the Pink" (see review, Page 55), is, at heart, a piano and vocal record, even more than its popular predecessor, "Little Earthquakes." Never mind the guitar, orchestration, et al. -- those are mostly expressionist embellishments tacked on to the elemental core that Amos sets down.

"My piano and vocal performances were done first on everything," she says of the album. "Then everything else started to come in, and the songs were pretty clear about what they'd allow on and what they wouldn't. I'd start to get sick when I heard something that just wasn't gonna work. It was like an immediate to-the-bathroom," Amos says, feigning a throw-up motion.

Anyone too associated with the piano nowadays begs to be considered an overly earnest sort or, worse, a New Age artist. The 29-year-old Amos, on the other hand, is at least as profane as she is precious and as likely to write a song about wanting to kill someone as about faeries.

Forthright, in-your-face and almost exaggeratedly brazen, but not without a classic sense of the pretty and poetic, she just could be the missing link between Carole King and Kurt Cobain, New Age and hard core. Amos aspires toward the truer sense of the terms, given her penchants both for the confrontational and the cosmic. On her upcoming tour the New Age punk will be traveling sans band again, finding the uncluttered approach the best flight path toward her stated goal of "wanting to shake some emotions loose inside."

"I like the freedom of being alone because there's an intimacy that I develop with the audience that I wouldn't otherwise," she says, munching on popcorn in her record company's West Hollywood offices. "I mean, they could just as easily bond with the drummer. And the more distractions I give them, the easier it is for them to avoid what I'm talking about."

Only at one point in her life did Amos more or less give up the piano. It was also, not coincidentally, the point at which she gave up her principles.

"I'll show you a place where I ended up on my kitchen floor of my flat," she says -- quickly adding the substitute word apartment, suddenly mindful of the fact that she's not in England right now. Where she is is Hollywood, driving around the area near the Chinese Theatre where she lived for several years in the late '80s. During the latter part of her seven-year residence, she labored under the band name Y Kant Tori Read, releasing one album even she says is awful. It disappeared with such little trace that Amos cultists now pay a premium for rare copies. At the time, the record's failure had her laid out on the floor in a depression for weeks.

Amos has no problem admitting she sold herself out, at market value, to get that record deal:

"Seven years I would turn in tapes to record companies; after seven years of rejection of my own music, I believed them when they said, 'This girl-at-her-piano thing is never gonna happen... Get a band, do metal, do dance, do whatever' -- and I did them all. I had my limit of how much rejection I could take. I didn't believe in myself enough.

"So I turned over my opinions to everybody else and refused to express what I was feeling in music anymore and invented this character for myself... I forgot that if it isn't in my heart or if I'm not getting off on it, maybe people could tell. I didn't think about that one. When 'Y Kant Tori Read' bombed, I didn't have any respect for myself."

Finally her depression was eased by more therapeutic writing. "I didn't even have a piano in the house. I'd trashed that before. So I rented this old upright and just started to write what I was feeling, and it became 'Little Earthquakes.' But it took Atlantic (Records) by surprise, obviously, when I turned in this music."

From all indications, Amos is the pride of Atlantic now, a critically respected artist who is a smash in Britain and whose last album eventually sold half a million copies in America. Insiders maintain that "Little Earthquakes" almost never got out of the gate, though, so dismayed were some label execs when they first got wind of its quirkiness. Fortunately for all involved, she stood her ground. Amos developed a flair for defiance early in life, chafing against what was expected of her both as a Methodist minister's daughter and a musical child prodigy in her native North Carolina.

"I couldn't become the concert pianist the teachers and parents wanted me to become," she says. "I couldn't sit playing somebody else's music for 12 hours and be told that my interpretation was wrong and be OK with it. How do you know how Debussy would feel about my interpretation of his music?

"I would sit and tell Bartok secrets. I would play him some John Lennon, and then I'd play something that I wrote and go, 'So this is what I wanted to tell you,' and then I'd play some of his music and feel like he was telling me something.

"I felt like I had relationships with these dead icons that, to me, would have been just hanging out in a house with loads of people, making music and probably having sex with most of 'em. Their music became a champagne social thing, when these guys were the Nirvana of their day."

Fundamentalism is still a sore point with Amos too. References to the symbols and trappings of Christianity are a constant in her work, usually with an irreverent bent -- as in the new album's "Icicle," which portrays a very young Amos masturbating while the family sings hymns downstairs, or the first single, "God," an archly intoned protest against the patriarchal.

"Lust and love were two separate things and should never and would never meet" is how Amos characterizes her upbringing. "What that means is you will always be at war with yourself... I was a walking dividing symbol... I was so ashamed of my passion."

In typical preacher's-daughter fashion, when Amos rebelled, she says, she "became a rock chick. Which I had to do. If I hadn't become a rock chick, I would be dead today, so long live hair spray."

Amos' post-"chick" previous album, but one that does, "Baker Baker," acknowledges that "I was the one that wasn't emotionally available," she admits. "We're always blaming the guys, saying, 'You're not sensitive enough; why can't you just be more understanding?' And then when they are more sensitive, we kick 'em in the face and go for the hockey player. It's like 'Dominate me, just dominate me. Not long -- I'll time you -- just a little!'"

She says she's come to believe that the battle isn't between the sexes but between those willing to grow and those not. That's brought out in several new numbers, including "Cornflake Girl," "Bells for Her" and "Waitress," that deal with " female betrayal," or the shattering of the illusion of the sisterhood.

Amos is constantly defying preconceptions: She speaks of different songs she has written taking on their own life and holding conversations with her as if they're spirits, yet she'll make light of people who have had too many "crystal suppositories." She holds evolutionary ideals but admits that she can come off seeming personally ruthless. She'll mock modern feminism in one breath and get almost tearful talking about Alice Walker's last book and the history of patriarchy in the next.

So, not surprisingly, the two most constant criticisms of Amos among her detractors are seemingly oxymoronic ones: that she's precious, or that she's overbearingly aggressive. She doesn't strain too mightily to deflect either barb. "I guess I'm both," she says. "It just depends what day you find me. I'm Sven the Viking on one hand, and then I'm Miss Mollusk."

She goes reflective for a moment, and comes up satisfied: "I don't know -- if I were hitchhiking, I'd liked to get picked up by me."

original article

[scan by Shawn Delahanty]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|