|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

Us (US)

February 1994

sexual healing

Tori Amos has gone from singing about rape to worshipping the goddess of fertility.

by Kim France

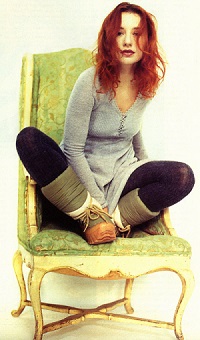

photos by Guzman

On a 'Tonight Show' appearance last year, Tori Amos straddled the piano stool like a lover, arching her back, caressing her undulating body and looking, for all the world, like a woman on the verge of a major climax. And while host Jay Leno seemed to like it -- "Hey, it works for me," he said after the performance -- this live sex act isn't for everyone. Not that Amos cares: "A lot of women have said I offended them," says the 29-year-old singer-songwriter. "And I'm like, 'When you get up onstage, I'm not going to bust your ass. If you want to stand there and not move your hips and think that's feminist, fine.' But I'm not doing this for any movement. It's about awakening my being. And part of my being is a sexual being. You know when they talk about 'the Goddess'? This is not a dry entity! This is fertilizing the cornfields! This is making things grow! This is a very juicy concept!"

With a face like an angel and a voice to match, Amos combines New Age loopiness with a no-nonsense bluntness that can leave listeners reeling. Her most recent album, Under the Pink, like her 1992 breakthrough, Little Earthquakes, sucker-punches an audience expecting sweet love songs and instead explores the rocky terrain and painful extremes of being female. Beneath the "pink" and pristine veneer of ladylike behavior, she implies, there lurks an unhealthy dose of anger, bitchiness and fear. Several songs detail the intricacies of women betraying one another. "Girls are the most vicious creatures alive to each other," she says.

It's not just her music that puts people off balance. After being shown to her seat at a quiet Greenwich Village bistro, Amos asks the waiter not to seat anyone at the adjacent table so that the interview can be conducted with a minimum of distraction. He replies that he can't make any promises should the place fill up. "We'll just fart, then," she says with a polite smile. The waiter retreats. And the adjacent table -- as well as most of the others surrounding it -- remains empty for the duration of her meal.

When Little Earthquakes was released, it was what Wayne and Garth might call a total chick record, with soul-baring, intensely personal lyrics. Immediately, Amos drew favorable comparisons to Patti Smith, Kate Bush and Joni Mitchell. Her haunting first-person account of being raped, "Me and a Gun," sung a capella, hit fans on a most visceral level. The reward for cutting herself wide open was an audience that identified closely -- perhaps too closely -- with her harrowing episode. On tour, her post-show backstage routine was less about cracking open a beer than listening to fans tearfully relate their own stories of sexual abuse. "There was such a freedom in dealing with it," says Amos. "But after that big outburst, everybody goes home. That big, initial realization has come out, but now the work comes. That's what Under the Pink is about," she continues, "healing and working through the violence and loss and finding the things that I'm made up of. I have other things in my life than just this experience."

The album also deals with doubt and frustration with organized religion, an obsession for Amos, whose father is a Methodist minister (her mother is part Native American). "[Popular religion] has gotten it wrong as far as the 'Shame, shame, shame, blame, blame, blame,'" she says. "And that whole idea that if you're not a virgin, then you've put an arrow in God's heart." She laughs. "Yeah, like, I'm sure God is really bummed out about that."

Predictably, Amos and her dad went to the mat regularly on these issues. "I'd see the pictures of the twelve disciples and say: 'Where are the chicks? I don't see how we can have objectivity if there aren't any babes around,'" she says. The two finally just agreed to disagree. "I respect his beliefs. -- we just see things differently. That's gotta be OK. I don't believe in a fascist state."

Her parents have come a long way, too, as far as dealing with their daughter's formidable talent. A child piano prodigy, Amos, who grew up in a suburb of Washington, D.C., was enrolled at Baltimore's Peabody Conservatory at age five. She was booted out at eleven for refusing to conform to its stringent regimen. "The one thing with being a child prodigy is, you get so much attention," she says. "And when you're doing mini-recitals, you start to get addicted to approval. As a kid, I loved this restaurant the Buttery, and when I did well, we'd go there. And when I did OK, we'd end up at Bob's Big Boy. Every time I played I knew it was about reward or not reward. That's kind of rough when you're six."

But Amos' love of music remained strong, and she spent the summer of her thirteenth year playing piano at clubs, including Mr. Henry's, a popular D.C. gay bar. Her parents rolled with it. "On the one hand, they have these beliefs," she says, "and on the other, they had this kid they loved. And they decided you either support your kid or lose your kid."

Amos was less enthusiastic about school. "I went because it was the law," she states plainly. As soon as she was old enough, she fled to L.A., where she immersed herself in the heavy-metal scene -- teased hair, thigh-high boots. She also recorded her first album, a bad attempt at heavy metal called Y Kant Tori Read?

After that crushing experience, Amos reconfigured her career and moved to London. "I was stagnant living in Los Angeles," she says. "And I was just drawn to London." Her boyfriend, record producer Eric Rosse, lives in the U.S., but the two see each other as often as possible. "We just call each other up from someplace and go, 'Hey, let's hook up,' and one of us jumps on a plane." And wherever Tori goes, her upright piano goes, too. "This piano gets so much love," she says, "because it loves back."

It is perhaps not surprising, given her eagerness to endow a piano with human characteristics, that Amos also believes in reincarnation. "I've been a Viking in loads of other lives," she declares. "I know what stealing the babes from the Irish coast is all about." Despite this pronouncement -- and many more like it -- Amos can't be dismissed as a bubble-headed neo-hippie. She doesn't believe in easy answers, knows that worshipping the goddess of fertility will only get her so far. "You can't just say, 'Let's meditate,' and it's all gonna go away," says Amos. "Sometimes you go, 'Hey, I've got a bit of a violent trait happening, and some sweet-smelling sage incense ain't gonna take it away.' I don't believe if you see a certain person or go to all the sweat lodges in the world..." She pauses. "I know a lot of people who have done all that and are still the most miserable people I've ever met." And with that, Amos takes a delicate slice of the spread tuna that has arrived at the table and proceeds to eat it with her fingers.

Kim France is the senior writer at 'Elle.'

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|