|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

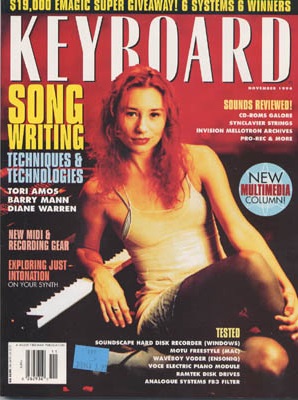

Keyboard (US)

November 1994

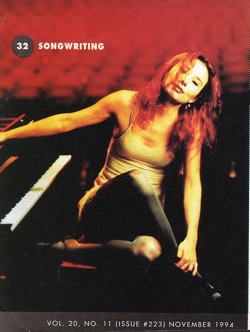

Tori Amos:

Dancing with the Vampire and the Nightingale

By Robert L. Doerschuk

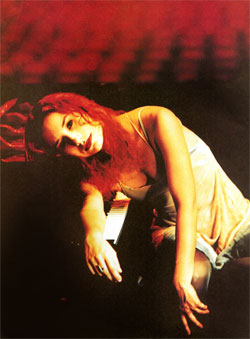

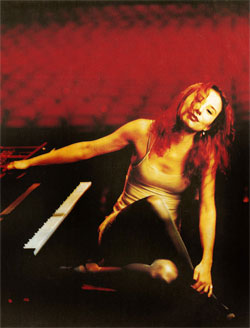

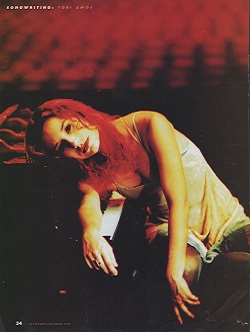

In the hush, Tori Amos waits behind a Bosendorfer Imperial grand. Bathed in light from overhead spots, she wipes the keys, adjusts her mike stand. A heavy backdrop hangs behind her, tinted light blue with patches of white. It's a winter sky, flecked with clouds, pregnant with snow, waiting too.

At discreet distances, technicians move their cameras, listen and talk softly over headsets.

The room is as still as a library.

At 11:54, Amos lifts her hands, lets them drift down onto the keys, and begins to play. The intro to "Icicle" takes form: The left hand crosses over and above the right in a 6/8 pattern, gentle yet unsettling. Like a mist, the sound rises and spreads. And now the sky behind the piano is alive: The blues and whites deepen into turquoise and magenta as shadows lengthen beneath the folds of the cloth.

This is soundcheck at NBC's Studio A, home base for The Tonight Show, one afternoon last August, three hours before taping. But for Amos, it could be anywhere: She's someplace else, somewhere once forbidden but now frozen for our scrutiny in "Icicle." The intimacy of her images draws listeners in, some as voyeurs, others as sisters who sense a kind of communion in progress. Her face shrouded behind a blaze of hair, she weaves back and forth, hovering, leaning, riding the delicate pauses and surges.

What we're seeing is one of the most important phenomena of modern music: the songwriter/performer in action. These artists inhabit a world apart from that of the Gershwins, the Bacharachs, the Diane Warrens and Barry Manns. The later were and are craftsmen, the guardians of a discipline with clear forms and limits. Their goal was to write tunes that anyone could relate to, with artful but unambiguous lyrics, and melodies that make the whole world sing. This tradition celebrates the theology of verse, chorus, and bridge; the old structures are adorned, highlighted, even nudged here and there, but in the end left inviolate.

No structures bind the songwriter/performer. These artists are bound not to preserve form but tot tap into their own springs and let the music flow as it will. Their craft evolves along the lines of their own idiosyncrasies. To a degree, they strive more to confess than to communicate. One must concentrate to decipher their lyrics, whose poetic obscurities can make the glib wordplay of Cole Porter seem strained and phony by comparison. There is more freedom than formula here, but also more risk: Those who would create at this personal a level accept the responsibility of being honest with their public, along with the possibility that the well may run dry if their lives devolve into a routine of studio, stage, and hotel suite.

None of this escapes Tori Amos's attention. People clamor for her time; her calendar is jammed with concerts and interviews. Yet the same thing that brought her into songwriting as a prodigy student at the Peabody Conservatory guides her today. Even here, hours before three minutes of intimacy with America on The Tonight Show, she can build a private space around herself and the piano, in which she can keep the channels open, the channels through which experience and reflection transform into sound, then return as memories to be pulled out again some other time.

With just two full-length albums to her credit—Little Earthquakes from 1991 and this year's Under the Pink—Amos has many years of work ahead of her. Or, more precisely, many years of wrestling with the muse, of looking out at the world and back inside for a way to respond to it. Of course, this has already been her life for most of her life. Her manner is that of one who has survived the ravages of creativity: She stares challengingly into her interrogator's eyes, uses candor almost as a weapon. She can be tough and provocative, yet feelings run like a river beneath her words and surface often as tremulant whispers. She is completely alive, as artists of her calibre need to be.

Her only request seemed odd—that we use no exclamation points in writing up our interview. On reflection, though, we understood: Her words, like her music, must be allowed to speak for themselves.

Why do you write songs?

[Long thoughful silence.] I remember walking down the hallways of the Peabody Conservatory and hearing the same piece being played in ten rooms, pretty much all the same. Some people's chops were better than others'; usually the kids from Asia were better, because they were precise and incredibly disciplined. The Jewish kids from that part of Baltimore had a little more humor in their work; you could feel that. But you had to have such good ears to really know, because they all were playing the same piece. I knew that I couldn't play this piece better than any of these people. It would probably be very different: You'd know where the redhead was, you'd figure out which practice room I was in. But I'd never win any competitions, ever, because nobody was interested in my take on Debussy. I never won anything. I always got marked down. Always. I had big arguments with these people, that these guys were pushing the limits of music at their time, just like John Lennon in his time. To understand their music, you have to understand the time. You have to know what's going on around them, especially when there's no lyric, when it's all music. Nobody, I thought, ever got the feel right. So I knew that if I was just gonna be playing some dead guy's music for the rest of my life, I'd probably never get a hearing, because their impression of what the dead guy should sound like was not mine at all.

But going even further back, was there ever a time when something in you said, "I want to make my own notes and words"?

I was seven [at Peabody]. I already knew what I was going to do. It was over when I was seven, a done deal. I was already writing. I didn't know how good or not good I could be. I knew that I could probably figure it out musically, but word-wise I was writing "The Jackass and the Toad Song." But I've always been a bit of a romantic. I'd be five years old, lying on my bed, with the afghan over me, squeezing my legs together and thinking, "Something should go here one day." I wanted to run away with all those guys, with Zeppelin and Jim Morrison and John Lennon. I [recently] told Robert Plant that I really wanted to pack my peanut butter and jelly and my teddy and my trolls and come find him.

So even then the power of songs being done by the people who wrote them was something you could feel.

Yeah, I was totally conscious of that at five. It's funny, because I think I'm more affected by those writers than the ones who were happening when I was in high school. I wasn't really affected by what was going on in 1979. I had checked out; I was just listening to my old records. Somebody played me the Sex Pistols after they had come and gone, and I we'ed in my pants. I said, "Shit, my father never showed me that this existed." I felt absolutely inadequate when I heard the Sex Pistols and the Clash, going, "Where was I?" I mean, I made Zeppelin and the Beatles and all those people when I was five. . . . Actually, Zeppelin didn't happen until I was nine or ten, when I started to bleed, so it was totally perfect; I was all ready for Robert.

How did those sorts of influences affect your growth as a songwriter?

First of all, I cannot contrive a song. I'm not nailing people who can. I know some very good writers who I respect a lot. They're called to do something for a movie, and they can come up with it in two weeks. They're not schlock writers; I'm talking about people who don't do hack jobs. They've got two weeks, and they're watching the film, and they're getting inspired. And I'm like, "How do you do that?" I don't care what you offer me right now: If the fairies don't sprinkle their little wee on my head, it's not gonna happen. I can't make it happen. Now, say I'm walking down the street, eating a banana, and something happens—four bars, with a sketchy lyric. If you give me two weeks, maybe I could develop it, just on my skills and craft alone. I'm not telling you it could be great. It might be passable. But there are certain songs I look at and say, "I would not change a breath."

In your performance?

Not my performance. I'm talking about, "That is how the girl wants to be. She's created. So she has seven fingers and 18 toes: She quite likes it, thank you very much." I was having this conversation with a friend recently, another writer, who said, "What happened to some of these great writers?" It's very funny how a woodworker or a cabinetmaker gets better with age. They don't forget how to make a great table. But how come some of these songwriters can't write songs anymore? It goes beyond being a craft. John Lennon talked about being able to tap into a source that's always there. Nobody knows where the freeway on-ramp is. You don't know where to get on and where to get off. Nobody can tell you the formula, because there isn't one; it's not gonna happen. You don't write "A Day in the Life" by a formula; it's not gonna happen.

Yet there are those who rely upon formulas as a device for writing songs. Almost by definition, these writers tend to be prolific, because they have a formular that they can haul our and use again and again. Perhaps the real artists avoid formulas in order for songs to be real.

Well, we have to remember that hit records and good songs are not synonymous. Maybe in the old days, a little bit. But now most hit records are not great songs. I'm not saying that those formula writers cannot stumble on something. But at a certain point, it's not about formula writing. I know I'm going back to the Beatles, just because that's a big point of reference, but how consistent can you get? "Eleanor Rigby"? "Norwegian Wood"? How many great songs and hit songs do you get? "Scarborough Fair" was a big blueprint for "Tear in Your Hand" [from Little Earthquakes]. I remember John Lennon talking about listening to songs that he loved, then changing them to make them his own versions. He would say, "God, I love this song. I wish I'd written this song." Then it would come out totally different. You might not even know what song it is that inspired you to do something, but there is that ingredient. Sometimes I do think that we're really just rewriting songs. There are only 12 bloody notes, you know. So I'll listen to some song and say, "Why didn't I write that?"

Because it speaks to you...

...as if I would have written it. I could name five songs, right off the top of my head, that I would have given my right arm to write. [Joni Mitchell's] "Case of You": You don't get it any better. A better song hasn't been written. I don't care what female singer/songwriter you throw up in my face: None has done anything in the league of "Case of You," me included. I sing "Case of You" almost every night in concert because of that. For a woman to be able to say what that says, with that kind of addiction and yet that kind of grace, is just not done. Even Zeppelin and those guys listened to Joni. They were totally influenced by Joni. It kills me when the metal guys or the hard rocking guys who are more posers than anything will show up and say, "You know, all the guys in my band are embarrassed to like you, because they're into Zeppelin." And I'll say, "That's kind of funny, 'cause I just did a duet with Robert." I don't think people understand that with songwriters, it's not about volume, you know?

When you recorded "Angie" and "Smells Like Teen Spirit," you seemed to get more inside those songs than most people who would just do a simple cover. It wasn't a question of adapting them to your style but rather absorbing them into the heart of your language as a writer and performer.

Some people see a song as the beginning of the tune to the end of the tune, with a peak or a climax. Everything kind of builds to that, and then it either stays and takes you out that way or you bring it back down again for contrast. But when I'm playing a song, the measure becomes this. [Amos spreads her hands wide apart.] Instead of this area being the song, the measure becomes this. Within the measure, where is our breath? The most important thing to me as a songwriter is the breath. The most important thing I could ever say to somebody is, "Sometimes I just breathe you in." From where I come as a writer, breathing is sacred. The breath within the measure is sacred. If you don't know how to use breath, then you're not using the most important notes. The great writers really understood that.

That may be why you stretch the idea of song structure further on Under the Pink than on Little Earthquakes. There are more extra bars and beats, more irregular repetitions. You get more into the idea of breath, with the songs extended to fit that concept.

Yeah, totally.

"China," from Little Earthquakes, is a beautiful tune, but perfectly symmetrical. You don't hear a lot of that on Under the Pink.

Well, the first part of "Yes, Anastasia" [from Under the Pink] is a good example of free form. "Anastasia" was written how you hear it. I wrote that whole first half with a tape recorder: The second half was written first, and then I was just noodling, just stream of consciousness with my ghetto blaster on. It took me six weeks to learn the first half of "Anastasia" from that tape, because it was all about free form. I'm much better when I've never done something before, because when I try to do it the second time, I'm recreating instead of creating. That changes everything. I usually don't get it together enough to finish a work like that; it's like I've got too much pesto on my noodles. I'll only get a couple of measures, and then it gets all jumbled. Then I start screaming and hating myself. It's just bratty prodigy behavior, because I get in my own way a lot. Sometimes I don't have the discipline of a more formulated person. Bridges have always been my strength, but sometimes the rest of the song is like pissing in the wind: The land masses on either side of the bridge ain't so great. I've got my Coleman stove and my little jacuzzi on the bridge, because sometimes there ain't nothin' on the other side.

Does the bridge often occur to you first, before you've even got the main theme of a song?

Believe it or not, sometimes I just write bridges. I'm writing a piece, and it becomes a bridge.

How can you tell that a piece of music you've got is a bridge rather than an embryonic chorus or verse?

Because it just wants to occur at that place. The great thing about a bridge is setup and payoff. For instance, right now I know I have a chorus for something. I've just started writing something for the next album, and this came to me in a dream form. I pulled my own hair to wake up and remember it: It was like Evan Dando [of the Lemonheads] at my piano, but it looked like Anthony Kiedis [of the Red Hot Chili Peppers] and it sounded like George Michael. When I woke up, I wondered if I had to give 'em publishing [laughs]. Now, I know this is a chorus. But I've set it up seven different times. I know the chord I need to come from; it's like, I don't smell the apples baking in the oven unless I come from this place. And yet the thing that I'd written for this place, I've given to another song, because it isn't right for this. You see, sometimes you can't be analytical. It's like, "I hate that fucking bitch, and if you put me next to her, I'm gonna mutiny." So the different parts have personalities, have souls. They're very real to me. I'm just translating them; they already exist somewhere.

In your Sept. '92 Keyboard interview, you explained that you got a physical reaction, literally felt sick, when you wrote something that wasn't as good as or as appropriate for a song as it could be.

Yeah. If I could get that way with men, I'd be out of trouble [laughs].

Here, too, you're using very un-technical language to describe how you do your work. In analyzing their own songs, most professional writers would say something like, "This melody leads here, so of course we wanted to do this key change over there, because I could resolve it with that."

That's never happened to me in my life. I'm trying to kiss a guy, and this song is pulling my hair and going, "I hate what you've done to me. I hate you." And I'm like, "Excuse me, I have to go deal with my song." Everything is secondary when the songs are coming. I don't know what kind of mother I would be; it would depend on how the songs felt about the baby. I'm a musician before I'm a woman, no question. I'm just beginning to kind of feel like I'm a woman and that I can do that kind of stuff, like have a human baby. I think that would be much less demanding than song babies, because sometimes it takes three years to create a song baby. And they don't go away. They're always in the back of my mind, and I'm like, "I hate singing you, already. I'm so sick of you." But they'll say to me, "Go listen to [Chrissy Hynde's] 'Brass in Pocket.' Why couldn't she have created us?" A whole relationship happens with the songs. Maybe because I've been playing since I was two and a half, I take for granted that the technical side will be right, because if it isn't good, it won't happen; I'll just throw up. Someone could sit next to me and tell me what's wrong with my song, and I would say, "But I can eat apple strudel. That's all that matters; that means I'm right." If I wasn't right, I couldn't eat.

You still write at the piano. How do you feel about sequencers and samplers as writing tools?

That's not my instrument. It is some people's instrument, but they're not piano players, not really. If they were fair, they wouldn't tell you they are.

Many of them, in fact, come from a piano background but have moved into new compositional techniques because they feel that the sounds can stimulate fresh ideas.

I can buy that. A lot of these people are very rhythmic, so they hear a sound and make it a rhythm. Then they work around that. Their work might be a little more diverse than mine—I'm talking about the good ones—because sonically I have one instrument while their thing changes constantly. They manipulate sounds, and my sound stays the same, although I can change what it does. It's a choice. It's not like a victim thing: "Why can't I have a bitchin' sound, like all those cool cats?"

Of course, the interaction between you and the piano is central to your work.

Well, my records wouldn't sound the same without the piano. That's why I play alone. Without the piano, my phrasing, my breath, wouldn't be the same. It's like the tide coming in, that pull of sand and sea. It is a relationship. It's the exact moment where you hold that note for that extra millisecond, and you're pulling back on that vocal, and the sustain's riding it all, and you add something in the left hand, and you're holding that note, and then the piano just knows when to come. It's about doing the tango.

In terms of lyrics, commercial songwriters can be like caricaturists who scale complex emotions and issues down to bite size. You and other more personal writers, on the other hand, are more like abstract painters.

You're right, but my intentions for writing have changed. There's a time when you want people to sing your songs with you. If you didn't, you'd keep them in your living room. Let's not lie to ourselves; that's the truth. Even I could tell you I'm writing because it's my form of expression, there is a need—that is a fair word, I think—to have them shared. Sometimes I'll listen to work that I've done, and I'll go, "I'm not in that place anymore. I couldn't write like that if my life depended on it. But I do understand an element of it that I would like to have in, say, this next piece." I do like that approach of, like, peeling your skin off. Although the whole concept of Under the Pink is about peeling the skin off, that's more of an abstract work, whereas Little Earthquakes is more like a diary. That was a conscious choice. I didn't want to write the same record again.

Thus the more flexible structures on Under the Pink.

Yeah, but sometimes it's a little more lyrically detached. They [i.e., listeners] can really crawl into the painting. I wanted Under the Pink to be more abstract, for many reasons. I was really into certain poets at the time, like e.e. cummings, and painters like Dali. I had this whole thing going where I liked codes and going with your senses. It was a bit of a maze, and you as a listener had to work to find out where we were going. Little Earthquakes was a bit more voyeuristic. You could sit back and watch this girl go through this stuff. You can't on Under the Pink; you have to go through it to understand it.

Bust isn't there a line you have to draw, not just as a songwriter but as a human being? There must be a limit to how much you are willing to reveal in your lyrics.

Funny you should sat that. Since before I wrote Little Earthquakes, I've had a pact with myself of no censorship. See, if you're a songwriter and people don't really know who you are, that's one thing. But if you're singing your own songs, it's a little different in this respect: I've found that the more known a writer gets, the less powerful and exposing their work gets, because the more they get known, the less they want to expose. I've caught myself trying to censor recently, going, "Oh, my God, they're gonna know who that is. And they're definately gonna know who he is." But this is not about putting names next to things. That's irrelevant. If people want to speculate, they've missed the point.

But most people don't know who you're referring to in your songs. They don't know the people who affect your life and work.

Yeah, but some of those people might know who I'm writing about, just because the more you get known, the more people know about who's in your life. So sometimes there's a thing about, "Do I really want people to know that I think this?"

I doubt that Ira Gershwin ever worried about that kind of thing.

Well, he didn't say anything that anybody needed to worry about.

Unlike Ira Gershwin, or folks like Barry Mann and Diane Warren, you and your songs are inseparable. Not many pop singers are going to cover your tunes.

No, although I wish Metallica would do one [laughs].

Your songs specifically reflect your experiences. Whether listening from, as you put it, a voyeuristic standpoint with Little Earthquakes or working through the abstractions of Under the Pink, would people ever be able to get as fully into your work as, say, "Someone to Watch Over Me"?

Look, "Someone to Watch Over Me" ain't gonna keep a girl from jumping off a fucking bridge like "Me and a Gun" [from Little Earthquakes]. Maybe if the person was on Quaaludes and had some weird sick sense of Nelson Riddle and Linda Ronstadt, and she was in love with some guy and heard it because of that, but give me a fucking break. Everybody understands basic emotions: feeling like a coward, wanting to kill some cunt and having no remorse about it. It's like, "No, I don't feel guilty about this. What I feel bad about is that I don't feel bad about this." That's what I have to look at. I try and crawl into my unconscious, and it's not that different from what's inside any of us. All of us have a bit of the vampire and a bit of the nightingale. But don't tell me that the hardest cats rockin' out there right now aren't afraid of pain. I'm just saying, whatever your lifestyle, whether you bring me one of the hardest rockin' dudes in the business or Bambi, they're all bummed out that Mom's gone.

The paradox is that the more you personalize, or Tori Amosize, your songs, the more universal they become to those who work to get them.

But I don't ever think that these are Tori Amos songs. I translate them in such a way because of Tori's experiences that would be different from so-and-so's experiences. But, as I've told you, these songs already exist. I'm writing a song right now about, no matter what I try to do, this person doesn't want what I want. Now, anybody can understand that. I mean, how can you not want to sip from a yummy chocolate soda or touch feet together? Even if you're the person who doesn't want it. It doesn't matter what side of the fence you're on. The rapist knows "Me and a Gun." The boyfriend of the girl who was raped knows "Me and a Gun," because he's had to live through it in a different way. The parents of the girl. . . . We could go on and on. But on this new song, they're so afraid of getting hurt that they won't open their heart. They know.

Emotions are very simple. I don't find them complex at all, to be quite honest. The girl who got laughed at, or the girl who was laughing at the girl: You're one or the other, my friend. Or there is one other option: You're the girl who's trying to divert attention so you don't get laughed at, and you're trying to stay friends with the girl who's laughing at the other girl. That's where I was; I think that's where most girls are. You're trying to stay friends with the girl who's laughing at the other girl so you won't become the girl getting laughed at. That's cowardice. But that's what a lot of people understand. So I write about being in those shoes, because it calls up those things in us.

I can't imagine writing if I'm not experiencing a life. If you have no life, if you're not being open to things, whatever they are, then all you're doing is repeating yourself, because all you can do is write from this one thing that happened to you when you were 16. You're writing the same song over and over again; all you're doing is changing the scenes. There's a disease in the writer's community that says, if you grow and you start to develop yourself, if you don't keep a debauched existence, where you're always victimized or whatever, then you have nothing to write about. A lot of songwriters get into this mode if they're successful from this point of view of everything going wrong in their life and being in pain, although you never really experience pain until you start really looking at it. That's when you're gonna know what your pain is, when you start healing; otherwise, you're just part of the quagmire. John Lennon is a perfect example of somebody who was always having different adventures, growing, experimenting. But I do see a lot of writers not experiencing life because they don't want to let go of their success.

In his last work, Lennon even turned domesticity, the antithesis of debauchery, into art.

Well, who says that just because you fall in love and you open your heart to somebody that you're not gonna have more passion, more angst, more to look at than you ever had? The more you expose yourself to different feelings, the more you have to draw on. Obviously, if you're in a complacent relationship, your work might sound that way. But why does growing have to be synonymous with complacency? There's so much self-destruction on the artist's side. Not necessarily on the hack's side. Hacks aren't self-destructive, because they've got a business to run. But the artist will do anything to keep the machine going. We're so afraid to write things that won't be accepted. Well, I believe that audiences get bored very quickly.

Bored with someone's output over a period of years?

Yeah, at a certain point. Maybe you know it even before they do, because you feel it.

As your world becomes more infected by fame, how do you keep in touch with the reality of life?

Look, if my whole live was . . .

Not your whole life.

Wait. If most of my life was about going into the studio, making the record, doing the video, doing the tour, living and breathing only that, at a certain point, what would I fucking write about? I know that. Now, there are some very good ones out there whose work is still about one kind of energy. Say it's anger: That's all it is. Well, guys, hello? Can we have maybe a different angle on your anger today? All the angry boys out there talk about how they can't have this stuff. Now, I adore angry boys. I'd make 'em all apple pie with cinnamon ice cream. But they all talk about how they can't have this and they can't have that. They've got this whole movement based on what they can't have. And I say to them, wrong. It's a choice. They've chosen not to have certain things. And none of them takes any responsibility for that. Those boys are gonna get interesting when they start to go, "I choose not to have love." Come on, boys. Let's say something interesting for a change, instead of, "I can never have this or that." That's your choice, because you think you're shit. There's very little responsibility for their part in it. They don't own up to, "The reason I can't have love is because I think I'm gonna shrivel when I'm with this woman, because I don't think I deserve her." Let's go into the why. To go into that, you have to live. You have to open up to these things. You're not gonna get to these answers by I-IV-V-fucking-I.

And it's not just the boys. Some of the girls do it too. Ay-yi-yi, can we stop blaming the guys here? We can blame them for what they've done, but then we have to balance in what we've done. The work isn't interesting when people aren't constantly discovering. We're stopping our lives as writers because we think we won't make great art. Who has put this thought out there? It's like a virus.

You're saying that there's a loss with respect to the talented writers who could have said so much before getting stuck on a single riff.

Totally that's what I'm saying. It is such a sense of loss. I'm not gonna mention names, but I'll watch something and go, "I know that this is very calculated." Once you've been on the other side, you know what it is and what it isn't. You just smell it. You're like, "This person has so much. They could go further than they ever thought they could go in their pain and their darkness." I've always said that Lucifer understands love better than anybody. You know he's done a mean tango with Greta Garbo a few times. Really understanding love is the only way you get to that side of things. Otherwise, you're just renting videos. It's HBO. These guys and girls who write about one more torture device over and over again? That doesn't scare them. That's not a challenge. And that's not challenging those kids who really are screaming. Talk about pain: If they want to experience pain, they should go hold hands with the little mermaid. Then they'll get scared shitless because they'll have to be real.

The pain industry that you're describing . . .

That's a great term for it. I guess I'm part of it too, in a sense.

. . . strips pain of its validity. When people tire of hearing songs that tell them how miserable they should be, they're stripped of the opportunity to feel real misery.

And they become parodies of themselves. It's so theatrical. Where's the real experience, so that when you take it to theatrics the foundation is still strong? But when it's just about anger for anger's sake . . .

. . . you're describing the fashion rather than the guts.

It is a fashion, and it isn't really that deep. We can all be a bit seduced by it. There's a masochist in me too, but my masochist is getting a little bit bored. It's not getting satisfied by those guys anymore. It's like, "You think that's painful?" My God, Baudelaire and Rimbaud were talking about and experiencing the heart. But it's so easy to contrive something. You know, "We're marketing dismemberment this week. That seems to be what kids want so, no problem, we'll do it." The whole point is that dismemberment isn't darkness, is it? It's just dismemberment. It's like, that's why God created video, so that you don't have to do any work on yourself. It's just a good distraction, an alternative to getting to what darkness is. The music business is packaging darkness, but for the most part, I think it's just a parody of darkness.

Look, I'm just saying that the writer's community has been given a drug. "Tori takes another step in her life, so she won't be able to write songs like 'Silent All These Years' anymore." Guess what? You're right. She'll never be able to write that again. So why is that a bad thing?

original article

[scans by Sakre Heinze]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|