|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

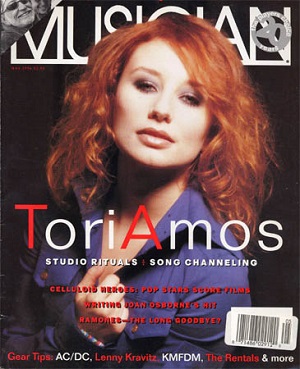

Musician (US)

May 1996

Voices In The Air

Spirit Tripping With Tori Amos

by Robert L. Doerschuk

photographs by Mick Rock

Late autumn in Surrey, England. Gray sunlight illuminates the afternoon mist.

An empty swimming pool, incongruous in this landscape of trees, ponds and

horsepaths, cuts a rude gash into green loam. Skies are overcast; clouds rush

toward the east, toward the cold horizon, racing the darkness. This is the

picture seen through the windows of Jacob's Studio, near the village of

Farnham. We're in a spacious room, with high beamed ceilings. To our right is

the breakfast chamber, where scones grow stale and coffee cools below framed

prints of schoolboys on a soccer field. From our left, music booms through the

wall - a demonic harpsichord figure, repeated, repeated again, and again.

Behind us is a Bosendorfer grand piano, big as a battleship, black as velvet.

Next to it, fragile by comparison, is a harpsichord. A single bench sits

between them, empty. Tori Amos is listening. She's a foot away, and she's

somewhere else, in the music. Or even further away, in the place where the

music was conceived, a place whose spirits hover and visit, not always at the

most convenient moment.

After a few seconds, she's gone, past the Bosendorfer, out the door, up the

steps to the right, and into the control room. The sound here is clear and loud

- supernaturally loud for a harpsichord. There's no drawing room delicacy as we

hear Tori tearing through Blood Roses: Cranked through twin Genelec monitors,

the instrument snarls and sneers, reflecting the primal passions of the vocal.

"When chickens get a taste of your meat, when he sucks you deep, sometimes

you're nothing but meat." We've come a long way from Scarlatti , baby.

Engineers Mark Hawley and Marcel Van Limbeek stoically man the Neve faders.

Their concentration is remarkable, considering Amos's turbulence. She's

anchored herself, one foot up and one foot back, like Robert Plant leaning into

Zeppelin's roar, rocking back and forth, eyes closed. Momentarily she sinks

into a nearby chair, but then she rockets back up, shouting through the din for

this tweak, that fix. One hand whips out to yank Hawley's pony tail; she wants

what she wants now. Without a blink, Hawley nudges a fader, and Tori claps with

delight.

"Haulin' 'er in," she beams, her right

hand winding an imaginary fisherman's reel. "We're

having tuna for dinner." The changes that Hawley and Van Limbeek make in

this mixdown session for Blood Roses are matters of technique. In this case,

the amount and type of reverb on the vocal is the issue. But Amos, making her

production debut on her third album, Boys for Pele, isn't thinking in terms of technique. She knows her way around a mixer, and her ears are as big as any in the

business. Still, she's way past technique at this point - in the way she plays,

like Landowska being exorcised; in the wild Sprechstimme and abandon of her

vocals; and in her writing, which is more like channeling.

"Haulin' 'er in," she beams, her right

hand winding an imaginary fisherman's reel. "We're

having tuna for dinner." The changes that Hawley and Van Limbeek make in

this mixdown session for Blood Roses are matters of technique. In this case,

the amount and type of reverb on the vocal is the issue. But Amos, making her

production debut on her third album, Boys for Pele, isn't thinking in terms of technique. She knows her way around a mixer, and her ears are as big as any in the

business. Still, she's way past technique at this point - in the way she plays,

like Landowska being exorcised; in the wild Sprechstimme and abandon of her

vocals; and in her writing, which is more like channeling.

In mixdown, she's a terror. And, most of the time, she's right. By the end

of the session, with dinnertime long past, Tori has finally completed several

hours' worth of microscopic nudges on the reverb. And damned if it doesn't

sound a hell of a lot better than it did that afternoon, when we watched her

drift into the call of the music, the prickly filigree of Blood Roses...

Something just happened. Your

attention wandered. What's going on?

[Long pause, listening. Then, suddenly...]

What happens is, the guys get it to a point

where they think they've got the bases loaded. We usually have the bases

loaded, but then the guy on second decides to do something stupid, so then we

have to load the bases with one more hit. This is a time when I totally stay

out of the way, because I'm not useful until the bases-are-loaded situation.

Let's be fair: Right now, we're only dealing with harpsichord/vocal, or piano/Marshall,

or piano/Leslie. We're not even in the big tracks, the involved arrangements.

But one little thing can completely change who she [the character in Blood

Roses] is. So I'll sit there and go, "This woman is five years younger than the

woman who's singing this song. The woman who's five years younger does not know

this song. She cannot sing it"

So you're dealing with issues this

fundamental even in the mix?

I'm talking about a quarter of a DB on the reverb. It's not me: She has got me by the fucking throat now. Really, I'm just translating. Once I accepted that, this isn't really about me, it's just about tapping into different sides of Woman. Then I can take on these parts. I don't necessarily think they're parts of me. I'm a part of that, but it's just part of this... this... being. That's what my life is. These beings... I don't know what

a shrink would call me. I don't want to know. But they come in and out, these

fragments. Like, I couldn't record Blood Roses for days. Technically, I could

play it. But she had not come. A lot of times, it's what's happening around me,

for me to get to that stage. It's who I run into, the phone call that comes.

Then it's like [snaps fingers]. That's why we live here, on location, because it's like, "She's here. Let's go."

How would you describe the technical challenge of capturing these nuances?

Well, the dynamics of this piece are very

extreme, and I have to get it on tape without squashing things too much -

especially the harpsichord, which they did squash. But what it is is, they

harnessed her. Just like they - quote, unquote - "had to do." I know when we've

lost a frequency of her. The "c" word is not "cunt" these days for me - it's "compression." That's what I told them: When you have a woman coming out of a church, and she's yelling and expressing something, and she's screaming, you do not try to make that okay. You get in trouble when you try to trim the edges. But at the same time, she's all over the road. I was ramming into that Neumann. I'm sorry, but

that mike was a fucking fried egg. We kept changing the reverb to make her a

plate [reverb] instead of a room. She kept telling me, in my ear "Get me a plate." Then the plate worked. The problem with the plate, though was that we kicked it up half a dB in parts because that's what's telling a story. Mark said to me, "Yeah, I like the plate, but it's not siting in the track the whole time." There are times when she's removed, in

another room from the track. So it's about kicking that reverb up beneath the

plate reverb. And it's changing everything.

There's a tension in the process between the purity of the character's essence and the mechanics of recording.

Well, I want to be part of the team in that mix

room, and I know that I have something to offer. Before, I would be standing on

top of mix desks, going, "A quarter of a dB! Get me a quarter!" They'd say it doesn't

matter, and I'm like, "That's the most ridiculous thing I've ever heard. Why

can you make it happen, then? If it doesn't matter, then why does the increment

even exist?" But at this stage, I'm tapping into her spirit. That girl is

existing [snaps fingers] now. The Horses girl...You'll hear what we do with the

mix on Horses. I'll tell you that story, but she's not here right now... [Very

long silence.] It's funny how anything can change her personality, so that you almost feel, "God, there's no compassion in her."

A big part of your job must be to nurture that concept in the minds of technicians who are used to hearing music as something more tangible.

I see it as Formula One racing. They're serious

car racers in there, but I built the car, so I know what it can do. I'm trying

to translate it. They know that, and they're trying to do the same. We all want

the same thing. What's the point of capturing what's getting me off today

because I had greasy eggs this morning? I want to hear her. I want to capture the

frequency. When you hear Beauty Queen, you are hearing this girl in that

moment: She's standing in that bathroom, watching those girls put on that

lipstick. I don't want us to be talking to her 15 minutes later about what she

realized in that bathroom. I want her to go back to that moment in the

bathroom: It's white. It's that funny fluorescent light. It's that tile, with

the green crud in between. It's those old toilets with the beautiful handles.

You can hear the sound of the water dripping. Time doesn't exist in that

moment. I wanted you to feel that kind of swimming, where you're almost coming

back from 15 feet under water, and you're coming up, and you're almost up. That's

what it's like in that bathroom, when you're looking and you're realizing what's

really going on at your table. That's what I want to catch. This is not a confident

girl. You are not at acceptance level. You are in her brain, getting triggered.

The little windshield wipers are going, and you're starting to see it from the

other side.

You want to bring that moment...

...always onto the tape. Every time you hear it, that girl is in the bathroom, putting on that lipstick. Every time.

How do you do that?

Well, the one thing I know is the smell they're

giving me. I don't hear anybody telling me anything; they're giving me

pictures. I love it when I have this moment, 'cause she's with me now. The

energy I feel rushing through my body is different than when I play live. That's

adrenaline, a response to the outside; this is "come inside." It's like I've

got my little plug, and she's let me plug into her. That whole thing of is it inside

or is it outside? She's in me, and I'm in her. There are times when her

particular volume is down and another volume is increased. But some of the

others are not present: They're sleeping, or they're having tea... It's

interesting that Horses and Zebra are coming out of this conversation around

Blood Roses. Horses opens up Blood Roses, so there is that intertwining.

Was it written that way?

Actually, Blood Roses was written to be the first song on Pele. I didn't finish it until I walked in to record it.

Is there something about this song that's harder to get to where you want it?

Oh, yeah. Zebra gets invited to all the parties.

Blood Roses doesn't get invited out a lot. She's all right about that. She's

very aware of a thing that I haven't dealt with: faithful anger. Anger

expressed faithfully. I think she's come to visit me to explore that side that I've

blocked away. There's a real stigma that gets put out on a woman's anger. You

become a madwoman, instead of, "I'm very loose about this moment, and you have

just really pissed me off." I'm trying to use compassion - passion coming into

its fullest - so that I can explore these "dark sides" of Woman: the anger,

that power, the destruction, the manipulation, the parts that lead to a label

of "hysterical" for women, to bring them into balance, the balance of destruction

and creation

Hawley and Van Limbeek are sharing a room at Jacob's Studio during the mixdown

period. It's an attic, really, with a couple of mattresses on the wooden floor

beneath a sloping roof; a small window overlooks bucolic surroundings. Everyone

on the Pele session refers to this garret as "the dorm room."

After hours of know twiddling and pony tail pulling, Tori and her team give

their mixes their toughest test. With DAT in hand, she leads the way up to the

dorm room and pops the tape into a machine. They flop onto a mattress as the music

plays through tiny speakers on severe, Shaker-style wooden cabinets, with

Marcel and Mark in attentive repose, Tori rocking back and forth, stopping

frequently to whisper some urgent observation into their ears. More often than

not, they grab the tape and head back to the studio for another round of

tweaks.

Both guys have been with Tori since her Under The Pink tour. Mark was, in

fact, a specialist in live sound; his credits include tours with Curve and the

Beautiful South in the U.K. He had heard and admired the Pink album, so when

word went out that Tori was looking for a road crew, he was among the first to

apply.

It was Mark who came up with the idea of building an acoustic box around the

piano when Tori recorded basic tracks at an Irish church at Delgany, County

Wicklow. "Under the Pink was done in Tori's room, as far as we know," Van

Limbeek explains. "To avoid crosstalk from the vocals to the piano mikes and the

other way around, they covered the piano with blankets. Mark and I could tell

this immediately, because we'd been working with her on the road for a year and

the sound of each room had such a great effect on the piano - even if you had

your head under the lid. You'd think that there's so much direct sound that the

room wouldn't matter that much. As it turned out, that's not true at all."

With the box separating the live piano and vocal tracks, crosstalk was not a

problem, and room ambience wasn't compromised. The piano was close-miked with

two Neumann U87s, positioned near each other under the raised lid, pointing

outward toward the bass and treble ranges. Bruel & Kjaer omnidirectional

ambient mikes added depth from about halfway toward the back of the church ath

the critical distance, which Van Limbeek defines as "the distance from the

microphone to the piano where the amount of reflected sound is equal to the

amount of direct sound."

At the very back, where the sound was most diffuse, they positioned other

Neumanns. Everything was recorded onto a Sony digital four-track; once tracks

were filled, they were digitally bounced to a Tascam DA-88 for storage, opening

up more free space on the DAT.

Everyone involved describes the trio's working relationship as ideal, though

living at close quarters doesn't exactly encourage mutual idealization. "I won't say Mark is arrogant," Tori says (or doesn't say). "But he's very committed to his beliefs, and he just kept stating and restating his approach. John [Witherspoon, Tori's assistant] would come back with, 'Well, this other engineer suggested...' and Mark would just say, 'No, this is the approach.'

"Mark and I in a room together are very

volatile; that's what makes it exciting. Mark knows my pictures: He knows when

I say, 'Girl in a bathroom,' that Beauty Queen is the front for Horses. He's

trying to translate what a bathroom is. He'll scratch his head, look at Marcel,

and come up with another element. He was a prodigy drummer as a four-year-old,

so he comes at this as a musician first and plays the board like it was another

instrument. But Marcel is a physicist. His world is my belief in something you

cannot tell me exists. What's what gets him off. Still, Marcel thinks I'm a bit

of a kook."

New York now, in the brisk freeze of early winter. The only fields in sight

are iced over in Central Park; everywhere else, from our vantage point in Tori's

suite, nature seems to have packed up and abandoned us. With the album finished

and ready for release, Tori seems calmer here, above the muffled racket of

civilization. Serenity, though, may be just another visitor, even less of a

presence than those who spook songs out of her and dance amidst the DATs and

detrius of recording.

Your beginning as a musician were

fairly conventional. At what point did you become aware that something

different was going on?

When I was very little. My career as a musician

was conventional when I got to the clubs, but it's what preceded it that fights

convention. I was playing before I could talk, so I didn't have the same judgment

when you learn music. I was playing without anybody's judgment, without anybody's

idea of what was good or bad. I just played anything I could hear. It's no

different from a little child who learns bilingually. It was very similar for

me, because the music was so complex that it wasn't like one language. I

learned rhythm, tone, phrasing, all those things from Bartok to Mozart to Sgt.

Pepper to Gershwin, through the ear as a very wee lassie, at a very instinctual

level.

But many musicians don't materialize

characters as you do. At what point did some other character say, "Hey, I need

you to materialize me through music"?

From the beginning. I was communicating with

other essences. It was almost like I had a window to communicate through music.

They all carried a piece of me in them; we're separate, but we're whole... But eventually,

with the loss of the relationship I was in, it occurred to me: "What if I

couldn't do this?" Eric [Rosse, Amos's former producer and lover] knows all this. He knows how intertwined we were, or I thought

we were. Sometimes I feel like I really shouldn't talk about Eric, yet there's

no way around not giving him a nod here and there because he so affected my

life at so many levels. The separation was the cliff I jumped off. When that

happened, that was the catapult of this record. Then many other things

happened, all at once. I'm not saying, "When it rains, it pours." It's more

than just one building fell down in the earthquake. It's all around you. IN a

lot of my relationships, whether friends or mentors or loves or parents, so

many things started to become a wall. This was mostly relationships with

different men. They were all just showing me different parts of myself that

were dependent. Each man in my life represented a need that I wasn't fulfilling

for myself. When you're an artist and you're with someone who is artistic,

there's almost an invitation to eventual breakdown. Yes. I think on some level,

that these men weren't used to being muses.

Yet I was never their muse, because I wonder if

they thought I was going to critique their work. The one thing that any man I've

been involved with knows is that I know rhythm and tone - yet I just want to go

with Oreo cookies and peanut butter and ice cream and garlic; I just want to have

a party! That's always been, shall we say, in my weave. The loose thread has

been that the musician in me is so ready to play and do a free-for-all, still

knowing what felt right or what didn't feel right, the more I developed my

music. I had boundaries as a musician, and yet I didn't need boundaries,

because I just know we're not going to F#. It's just not gonna happen. But as a

woman - and I have to bring this up, because this is where the content of the

work comes from - I didn't have this access that I had as a musician. I had

separated them from birth: the girl from the musician. For the most part, Pele

is about my response. The women really held the space for me to dive into on

this one. My women friends knew that only I could go after this. They would be

dragging me back by my hair, going, "Hello? Are you aware of what you just did

to yourself?" And I'm sitting here with veins ripped open, licking a little

blood from my chin, going, "No!"

When did they ask you that question?

When they saw me during this period of time.

Some of them would have to converse with the musician in order to talk with the

woman. It's almost like I've developed this compositional understanding - and

very little else. The musician has had more access than anybody to the

different sides, and yet sometimes she's not always completely interested in communicating with the other side. Maybe they'll exchange phone numbers [laughs]. And so the men I've pulled into my life are reflections of pieces of myself. Some were obviously bigger pieces than others: an eight-year relationship is a huge chunk of being. The whole record, though, is a gift to myself. No, let me rephrase that: What's been given by these songs is a gift to me.

Did any of these songs frighten you as you wrote them?

Professional Widow. Blood Roses.

Both of those are harpsichord songs.

That was instinctive. Sometimes I know I have to

do something, and then a little later I understand why. But Muhammed My Friend

surprised me too. I was singing in Christmas services [in '94]; I was with my parents. I was watching the Nativity, and

after a while I said to myself, "Wait a minute. There's something wrong here."

We were singing Away In A Manger. [Amos sings the first two bars of "Away

in a Manger" then sings the opening line to "Muhammed My Friend" with the

identical first three notes.] I kept getting more

and more into the perfect little love with the lullaby of Away In A Manger. I

started to get husky in the throat. I started to wonder who, with everybody

speaking of the baby Jesus, should come up to the cradle. And I found that, of

all people, I wanted to have a chat about it with Mohammed, because the Prophet

is the one who supposedly knows the Law. So I decided that they needed to talk about

the Law - the Law of the Feminine that had been castrated with the birth of

Christ. I believe that Magdalene was the Savior's bride, the High Priestess.

And that Magdalene was not a blueprint for women - meaning that this was a

woman who was honored as the sacred bride, not a virgin. We're talking about a

Woman. We have a Virgin matrix, but they needed the Woman blueprint: the

compassion/passion, wisdom, wholeness. But this blueprint was not a structure

that one could relate to Woman - until now. Think about it. It's just been

uncovered in the past twenty-some years. Even though women have been given

power to be heads of corporations, we're talking about not just power within

the hierarchy but access to the different fragments that make up the whole of

Woman.

Do many of your listeners understand

what you're getting at with these lyrical references?

Well, sometimes I kind of chuckle to myself when

I hear some girl saying, "Who cares about Mary Magdalene? That's over and done

with." And I'll watch her as she needs to seduce the men in the room and play

the little girl, do the pedophile dance, do the thing that girls have done for

centuries to get power from the outside instead of power from the inside. yet

so many of these girls will come to me with tears in their eyes and scratches

all over their wrists from self-mutilation, and I'll say, "I actually do

understand the obsession to be difficult." I mean, I was in absolute horror

that I allowed myself to be raped. Blood Roses is the on-the-knees version of

that, the ripped-open veins and the blood dripping, going, "Why is it my fault

now?" I'm just trying to negotiate on any level - "Mr. St. John, just bring

your son." [from Caught A Lite Sneeze]. You

know you will not gain strength from this path. You know you will not get peace

from this path. But you are addicted and on this path. You just know you need

energy from an outside source because you don't know how to access it for

yourself. Now, there's some energy that I did know how to access, and men would

be drawn to me for that.

What did Professional Widow mean to

you?

As I got to know Widow, I began to really adore

her candor. She was so cut off from so many other parts of being, but here she

is, deliciously convincing him [i.e., the black widow spider's doomed

male mate] to kill himself so she doesn't have to

leave fingerprints on his body. She'll make sure he showers before this all begins.

She's ready to extract what she wants from him, the current that she wants, and

the current won't be what she wants until he's dead. Whatever his addiction is,

she's convincing him that Mother Mary will supply it.

What other songs stand out for you?

There's one called Agent Orange. Naturally, if

we're talking about the boy/girl matrix, there's going to be a war zone at some

point in our story. It's kind of been a war zone from early on in the record.

As the record goes on - and on and on and on [laughs] - the vulnerability starts coming. Then you start

sleeping with one of the lieutenants from the other side because you ended up

at a country village and you forgot that you were on different sides. You know

how it is when war begins: The strangest, craziest things begin to happen. That's

when we start moving into something else with that break on the record after

Jupiter, with Amsterdam, with Talula. Now we're in the South - that whole smell

and taste. And we go into Agent Orange. If we're gonna have war, we have to

bring warfare in. I decided to make him a bodybuilder because that memory has

to transmute also - the skin. To become like tango, the idea of Tang, or the

idea of Orangina, an Orange muscle secret agent who we love... That song, Agent

Orange, is the one o'clock cabaret moment, where you've had a couple of

Amarettos on the rocks, and there's just a sadness. But you know that sadness

when you're still alive? You know you're not dead. You've got all your body

parts. You're all there. You've got a date. He's got a new love [Long

dreamy pause] And you go on with it.

~ ~ ~

In Tune With Tori:

Old Twists in Harpsichord Voicing

Piano technicians know the secret of good tuning: temperament. No, not being

in a good mood while tightening the strings - temperament is how tuners resolve

the mathematical impossibilities in reconciling the perfect octave with the

natural perfect fifths between the perfect fourth and the major third. Many

solutions to this problem have been devised, some more effective for the piano

than, let's say, harpsichord. And that is the crux of the issue for Tori Amos,

who wanted to play piano and harpsichord simultaneously on Boys For Pele.

"The harpsichord comes to life in other temperaments," says keyboard technician

Tania Staite, who tackled the challenge for Amos. "So every week we tried

different tunings. I had to tune the harpsichord as an average, shifting the

pitch of C very slightly in order that everything was midway between notes of

equal temperament, rather than sticking C [i.e., the C scale] in tune, which

would have made some notes vastly out of tune. The idea of using other

temperaments is that you end up with a lot more pure fourths and pure fifths,

rather than the way everything is equally out of tune in equal temperament. That

would have made some notes vastly out of tune.

"We used four temperaments in the end, the earliest of which was the Werkmeister

III, which dates from 1691. The instrument Tori used was made in Hamburg by

Christian Zell as a copy of an instrument dating from 1728; Werkmeister being

German, it was probably the temperament that the instrument was played in from

its origins. Chronologically, the next temperament was developed by Vallotti

(c. 1754). Then we went on to the Kirnberger, devised by a pupil of Bach around

1779. The latest temperament, which Tori used on Caught A Lite Sneeze, is by

Thomas Young in 1800."

Judging by the results on Boys For Pele, the impact of these alternate tunings

is subtle, if not subliminal. Says Staite, "I love the album, although except

for Caught A Lite Sneeze, for the life of me I can't remember which tunings she

used for which songs."

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|