|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

High Life (UK)

British Airways Magazine

May 1998

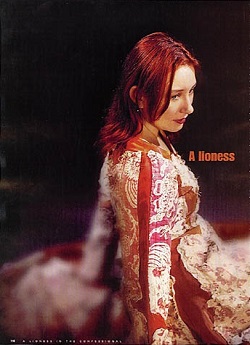

A lioness in the confessional

It's all fire and brimstone when singer Tori Amos decides to speak her mind. Mark Edwards pulls up a pew.

The British don't really get Tori Amos. They buy a lot of her records, but they don't really understand her. The Americans realise that she's a serious and dangerously subversive artist, using her songs to draw attention to the hidden truths of their society, their religion and their relationships - the ones that they would rather not talk about. The ban her records from the radio; and the hippest musicians - from Nine Inch Nails' Trent Reznor to REM's Michael Stipe - rapturise about her songs and clamour to collaborate with her. In Britain, however, she's been portrayed as a quirky kook, a cross between Kate Busy and the wacky neighbor from a US sitcom.

It's largely her own fault, mind. When Amos burst into the public consciousness with her 1991 album Little Earthquakes (her real debut with the plastic 80s rock band Y Kant Tori Read was largely ignored and is best forgotten), journalists were introduced to a woman who talked in a unique mix of 1950's gee-whiz American, therapy-speak and hippie slang, and who liked to use metaphors without making it clear that they were metaphors. Thus her tendency, for example, to refer to the stronger side of her character as "Sven the Viking" led to articles suggesting she thought she'd been a Viking named Sven in a former life.

Amos has wised up. These days she keeps a closer check on what she says. Our interview takes place in a windowless, airless, characterless basement room in the otherwise luxuriuos Lanesborough Hotel in London's Hyde Park. They call it the 'business center', but its main use is clearly for staff training. A flip chart in the corner contains the outline of an induction course for new staff, including an introduction to the company mission statement: 'always deliver beyond expectations,' it reads, 'never say no.' That would pretty much have described Amos' interview technique a few years ago, when any subject was up for grabs. Now, however, when I ask her a question with the merest hint of new-ageness about it, she decides I'm looking for the old kooky stuff and the shutters come down: 'Oh, I'm not going there, and you know it,' she says.

Her unique stream-of-consciousness approach to language remains intact; describing She's Your Cocaine, one of the songs on her new album, from the choirgirl hotel, she explains the relationship in the song like this: 'she not being me, she being the one that he's obsessed about, and whatever we think of her is whatever we think of her - probably we think about her in cruel.'

The woman in the song that the man is obsessed with could be amazing, concedes Tori, but equally, 'she could just be a black hole.' This is exactly the kind of relationship that Amos likes to write about - one with a hostile undercurrent. At any dinner party, she explains, 'there'll be a woman at the table who has all the men sucked into her pain. That type where it's just tragic, gorgeous, victimised needs-nothing-from-anybody, won't-call-you-back, nothing is good enough except slitting your writs and letting her drink your blood, and then you'll slit another part of yourself and then another part - she's a passive vampire.'

Oh, those passive vampires - they're the ones you've really got to watch out for. 'They don't admit they're drinking your blood, that's what makes them so dangerous,' Amos says. 'I'm a lioness, but at least I'm honest. I'm like: look, I'll rip your heart open and drink your blood. Cards on the table. And I like it when someone is honest with me. "Hey, I want to drink your blood." Well, okay - at least I know what you want to do.'

Tori's brutal honesty and openness about her feelings has attracted to her a particularly obsessive type of fan. They're the quiet, shy types whose school report cards said: 'doesn't play well with other children.' Tori accepts this and embraces it. 'I'm the queen of nerds,' she's fond of saying. Until her fan base got too big, Tori used to spend literally hours after her gigs talking to fans at the stage door, accepting their gifts, listening to their stories and giving them all big-sisterly hugs. In return they lapped up any available Tori product (her records always come out in several formats, since the record company knows that her fans will buy them all).

Her fans have also created a Tori universe on the Internet. In an ironic twist on Tori's regular church-bashing, her fans' home pages are called 'shrines' and have names like The Temple of Tori, and the First International Church of Tori; fans leave sixth-form, exercise book-cover notes like 'Tori is the candle which burns a hole in my soul and the needle that sews me back up after filling me with her music', and discuss which hair-colourant their idol uses (Clairol Torrid Torch Crimson, apparently).

From the choirgirl hotel is something of a departure for Amos, it's the first album that she has recorded in a band setting - with a drummer and programmer playing along with her - rather than as a solo singer alone at her piano. Influenced by the Armand Van Helden remix of Professional Widow, a track from her last album, which became a huge club hit last year, Amos has put rhythm at the heart of many of the songs.

'I wouldn't make that kind of record,' she says, referring to the remix. 'But the energy of it and the rhythm was quite inspirational for tracks like Raspberry Swirl. I was like, if I'm going to write a song, I don't want to just put rhythm on top of it, I want to write a rhythm into it, so it's part of the architecture. Another track, Cruel, is about that. It's not just written as a ballad at the piano and then you come up with a catchy rhythm.'

The album also signals her desire to move beyond the piano to embrace synthesisers and samplers. Despite a dodgy distant past playing synths - she once auditioned for Billy Idol's backing band - Amos has been loyal to the piano for the past eight years. 'I needed to do that,' she says. 'I just needed to be with that instrument for a long time. Until I got to the point where I knew it was okay to try other things because I knew that I wouldn't dishonour my main instrument - that the piano wouldn't feel abandoned.'

The new album is, perhaps, less of a cohesive whole than her three previous outings. Little Earthquakes was essentially Amos' diary, detailing in shocking honesty the events of her life, from her repressed religious upbringing to her rape by a fan. Under the Pink was themed around the idea of women's relationships with other women; while Boys for Pele (described by its authors as 'a journey to the underworld') concerned itself with her relationships with men.

'This time I felt the songs were a troupe,' she says of the new album. 'They all have different parts. Some are hanging by the pool having drinks, and some are in Suite 17, and some are answering the phone. But they're all in the same hotel. I saw them as individuals. They work separately from each other, but they know each other.'

The album may not be based around one unifying theme, but many of the songs did emerge from one event. Towards the end of her last tour, Tori miscarried. 'I was very ready to be a mom,' she says. 'It was a shock, and I was devastated. While I was pregnant I felt more love than I had ever really felt. And the love didn't go away. Feeling love like that, it changed me, even though the spirit didn't manifest physically. I didn't become a mother at this time, but I became a different woman.'

'I think when I'm going through a difficult time the songs tear across the universe to find me,' she adds, 'because we have a pact.'

The song Spark contains the lyrics, 'She's convinced she could hold back a glacier / but she couldn't keep baby alive / doubting if there's a woman in there somewhere.'

'You really question that you can't do this thing that's so natural, you can't come through,' says Tori. 'It's out of your control, you're helpless.'

Given this subject matter, it's perhaps surprising that choirgirl hotel is a much more 'up' record than Boys for Pele, more accessible and even radio-friendly. It's not simply an album's worth of difficult emotions. 'I didn't want the songs to just be the diary of what happened,' Amos says. 'They have many layers happening; I have historical references; and I'm always going to bring God into it.'

Indeed she is. Her father is a minister, and both his parents were preachers. Religion is a subect that Amos simply can't leave alone. 'You can't change what's made you,' she says. 'Religion is a huge part of why I write the way I write, and why I think the way I think. There are people I know who have become Christians from a different place - because they believe in Christ's teachings. Well, I have no idea what it's like to come through that particular door, because I know the shadow of the Christian church. I can't see Christianity like someone else.

'What I do in my songs is I take a flashlight into the confessional,' says Amos.

She describes her songwriting as 'diving in after secrets, seeking truths', but admits that there are many different truths out there. 'You know, if you wiped away all the stuff around Christianity,' she concedes, 'the basic teachings are real nice, like the meek shall inherit the earth.' She pauses for a moment, and smiles. 'Not that that's happened yet.'

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|