|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

Details (US)

August 1998

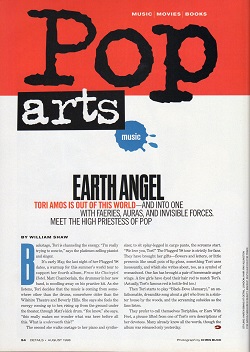

EARTH ANGEL

Tori Amos is out of this world - and into one with faeries, auras, and invisible forces. Meet the priestess of pop

by William Shaw

photo by Chris Buck

Backstage, Tori is channeling the energy. "I'm really trying to zone in," says the platinum-selling pianist and singer.

It's early May, the last night of her Plugged 98 dates, a warmup for this summer's world tour to support her fourth album, From the Choirgirl Hotel. Matt Chamberlain, the drummer in her new band, is noodling away on his practice kit. As she listens, Tori decides that the music is coming from somewhere other than the drums, somewhere older than the Wilshire Theatre and Beverly Hills. She says she feels the energy coming up to her, rising up from the ground under the theater, through Matt's kick drum. "You know," she says, "this really makes me wonder what was here before all this. What is underneath this?"

The second she walks onstage to her piano and synthesizer, to sit splay-legged in cargo pants, the screams start. "We love you, Tori!" The Plugged 98 tour is strictly for fans. They have brought her gifts - flowers and letters, or little presents like small pots of lip gloss, something Tori uses incessantly, and which she writes about too, as a symbol of womanhood. One fan has brought a pair of homemade angel wings. A few girls have dyed their hair red to match Tori's. (Actually, Tori's famous red is bottle-fed too.)

Then Tori starts to play "Black-Dove (January)" and unfathomable, dreamlike song about a girl that lives in a sinister house by the woods, and the screaming subsides as the fans listen.

They prefer to call themselves Toriphiles, or Ears With Feet, a phrase lifted from one of Tori's own descriptions of her devotees. Many already know all the words, though the album was released only yesterday.

That a dark thread runs through Choirgirl Hotel is not exactly a surprise. Tori's first album, Little Earthquakes, contained the song "Me and a Gun," in which she graphically sang the thoughts that passed through her head while she was being raped by an acquaintance. Her third album, Boys For Pele, named for a Hawaiian volcano goddess who demanded that boys be sacrificed in her honor, was sparked by her split from with her lover and longtime producer, Eric Rosse.

Tori has told interviewers that the earliest songs for Choirgirl were written in the aftermath of a miscarriage. She sings about the trauma of that experience in the song "Spark" ("She's convinced she could hold back a glacier, but she couldn't keep Baby alive.") and on the CD's penultimate track, "Playboy Mommy" ("Then the baby came, before I found the magic of how to keep her happy.") In both songs, her New Age cosmology filters through: The spirit of her baby chose to desert her, to go elsewhere.

To discuss this with her is to plunge into Tori's own hypersymbolic world, in which emotions are anthropomorphized or totemized, or take the form of unseen "energies."

It sounds like the songs are full of self-blame.

"There's a level of that. (pause) There's many levels to it. There's also a level of saying I don't want to face loss. I just don't want to take the chance. (pause) If you love someone, you're going to lose them at a certain time. You have to accept that Sorrow will be there. You better make real good friends with her, because she's going to be there, especially as you get older. And after a while, Sorrow becomes the deepest part of the ocean. You know, there are times that Sorrow tells the dirtiest jokes..."

Sorrow tells the dirtest jokes? That's a fantastic concept!

"She really does. I think Joy can be really snotty sometimes, too. I think she says, 'Everybody wants me. I'm the belle of the Ball.'"

TO SOME PEOPLE, this kind of talk seems nuts, of course. To Tori's fans, though, it's as real as the ground under the Wilshire Theatre. To them she is a musical Buffy the Vampire Slayer, kicking the ass of hidden demons that lurk in Sunnydale.

After the ecstatic encores, the touching of hands, the clutching of her own heart as if she is overwhelmed by their love, she steps backstage again. There, Matt Sorum from Guns N' Roses, short-haired and Armani-clad, greets her with a hug. Tori says, "When Matt hugs me, it says a thousand words."

It's an old friendship. She and Matt used to play in a band called Y Kant Tori Read [note from yessaid: this is incorrect, Tori and Steve Caton played together in YKTR]. She spent six years in Los Angeles, trying to crack the music business, trying to escape from her life as a Sheraton bar-and-lounge pianist in Washington, D.C. But the band was, infamously, a spandex-clad, big haired disaster.

Defeated, Tori sat on her kitchen floor, imagining that everyone in the L.A. music business was laughing at her. "But I wasn't going to go back to my father's house," she says, employing a typically biblical turn of phrase. So she started writing songs again, only this time they were less contrived and more revealing. "I have a lion's pride. Even though I've bitten into, like..." - she pauses to search for the right metaphor - "a rabid hyena - the music industry - I was not going to go back."

THE NEXT MORNING Tori is up early. She and her band are booked to appear on KROQ's "Kevin and Bean Show," playing in the parking lot of the Palace nightclub, just a few hundred yards from the apartment block where Tori used to live when she was a struggling piano player.

Whatever energies she is supposed to be channeling when she plays, they can be pretty wild. Tori is a dramatic performer. One moment she's a tender little girl, the next a hotheaded harpy: There's often something distinctly libidinous about the way she grinds her hips as she tinkles her ivories.

Between "Black Dove (January)" and "She's Your Cocaine," she takes questions from fans who go by names like Crystal Dawn. "Hi, Tori. I noticed you didn't thank the Faeries on this album."

Tori's fans are one of the more intense groups on the internet. Inspired by her example, they share anything from life stories to opinions on when screaming at her concerts is appropriate. They know that on each previos album has contained liner notes thanking "the Faeries." This time, to the concern of some, they seen to be absent.

"Oh, they're there," Tori replies cryptically. "You gotta find them. There's a special message on the record."

The fan is relieved: "Oh my God," she says "don't ever lose the Faeries."

Tori believes in invisible powers. She believes in past lives, ley lines (geographical concentrations of psychic energy), auras, and Faeries. (Not the cute, Disney kind of fairy. She has a phrase for that sort of sentiment: "Tinkerbell smegma.")

Her belief in the invisible started early. The daughter of a Methodist minister, Tori was the youngest in her family by seven years. Whereas some kids have one imaginary friend, Tori dreamed up an entire supporting cast. There was Clunky the Purple Monkey, later Timmy, then Mr. Spaghetti. Tori began rebelling against organized religion at an early age. Possibly the first time was when a visiting bishop had the audacity to lower himself onto the chair where Clunky was sitting. Tori started screaming.

"That's a good excuse for screaming at a bishop," I say.

"Oh, yeah," she says, laughing.

TORI WAS RAISED in a world of rich if somewhat confused, symbolism. Her father, Dr. Edison Amos, came from a strict, Bible-reading Methodist family. Her mother, Mary Ellen, on the other hand, was part Cherokee, and she would read Edgar Allen Poe stories to Tori at night. Her maternal grandfather, Poppa, would tell her stories about the old Cherokee ways. "With Poppa," Tori says, "there was a spirit in all things. You have a relationship to the spirit world or you have nothing."

I ask whether she believes that too. She becomes impassioned. "People try and make other people feel bad about getting in touch with their souls and their spirits," she says. "You get it a lot, especially in the cynical media. When people cut themselves off from everything except what they can touch, they are cancerous. The sad thing is, that's really evil... evil to yourself. You become the fascist."

Poppa died when Tori was nine. She remembers looking at his body in the casket. I tell her of a quote I found from her mother, saying that she doesn't think Tori ever quite got over his death. Tori looks surprised.She frowns. "She's never said that to me." Then: "I think that's probably accurate. At that time, he made most sense to me of anybody."

PIANO PLAYING STARTED at the age of two. It's been part of Tori as long as she can remember. "I was a musician before I realized I was female, before I was a girl," she says.

Another key moment came around age eight, when she realized something else fundamental by watching David Cassidy on The Partridge Family. "Well, I knew I wasn't a lesbian - I figured that out. But then I moved to Robert Plant. Nothing against David - I mean, you gotta give it up to David. He really did affect a lot of people, and he did what he did very well."

You played "Icicle" last night, your song about the discovery of your own body and about what you got up to on the bedroom floor while your parents were downstairs. Was that discovery a big moment for you?

"Oh, yeah. Not a moment - it went on and on and on. This was when I was ten. I remember my sister threatening she was going to tell on me because I asked her about it."

What a snitch!

"You know, she had been really threatened by the whole religion. And she was genuinely worried for my soul."

Did you think masturbation was evil?

"Well, I was always fighting the idea. My instinct was, 'This is natural,' but the belief system was that it was evil. You couldn't love Jesus and do this. You have to understand, I was doing this while saying 'Jesus, I love you. Jesus, I love you.'"

I was just expecting serious degeneration of eyesight, myself.

"Yeah, I know. People think their hands are going to fall off. It's a shame that people don't just say "Hey, don't do this while you've got food in the other hand. There's a place to do this...'"

TEN WEEKS AGO, Tori got married. She wore a blue dress. "Ice blue," says Tori. Her husband is Mark Hawley, one of the engineers she works with. The couple live in a converted barn in North Cornwall, the bleakest landscape in southwestern England, and Choirgirl was recorded in a studio on their property. It's the first time Tori has written for a full band, and that makes the record a departure. At heart, Tori is a progressive rocker, a classically trained musician who idolized Zeppelin. Written on the piano, her complex songs are full of little stop-start changes and ornaments; Matt Chamberlain's tribal-sounding drums sew the pieces together, giving the songs a far more organic feel.

Typically, Tori thinks that Cornwall contributed too: "The land feels really ancient," she enthuses. "The good thing about the loneliness there is that you're forced to be with yourself, to listen to the land. There is something running through that is just deafening. You harness it like electricity."

It's Monday and Tori's in NBC studios, preparing to appear on The Tonight Show With Jay Leno. She discreetly asks his people if Hawley can sit in the crowd and whether it's all right for him not to wear a suit. Though the two travel together, she does her utmost to keep him out of the public view. "That's personal," she says.

In rehearsal, Tori sits behind her Bosendorfer and adjusts the microphone. Suddenly she's worried about something. "Am I getting a funny chin?" she asks the control booth. "I'm thirty-four; I'm becoming Cher, I really am. Call the doctor." The conversation is stiltedly lighthearted. Nobody wants to play the raging diva. Tori has a makeup artist, Kevin, who usually watches the TV monitors to check for ungainly shadows: He can be tactfully forceful when it comes to persuading a camera crew to change their lighting.

Back in the dressing room, a hair-dresser puts curlers in Tori's hair. Karen, her wardrobe assistant, dresses her in a leather skirt. Kevin sticks tiny reflective jewels on her faces and arms and paints her eyebrows a bright maroon with a lipstick pencil. Tori knows about this kind of magic, too.

At eleven, when she wore braces and was self-conscious about her big, broad lips, the boys teased her.

"What did those bastards say?" I ask.

"You're face is a butthole," she answers. "Oh any part of your body is up for dissection by little boys."

But the older girls taught Tori about the power of makeup; she remembers being saved by lip gloss called Kissing Potion. Now it's as if she's donning war paint, ready to avenge herself on the boys.

Today's shoes are by Prada. The Ears With Feet take particular note of her footwear. They know shoes mean a lot to Tori.

How many pairs do you have? Are you like Imelda Marcos?

"No, no, no, no - shoes are architecture. And this might sound a little weird to you, but I'm very connected to the ground."

You wear four-inch heels and you're connected to the ground?

"No, I'm connected because I wear shoes. I'm always looking down to see which ones I have on today. And then I realize, Oh yeah, I'm on the earth."

Kevin, Karen and the hairdresser coo and fuss around Tori. As she prepares to leave the dressing room, they tell her she looks fabulous.

And after she's played "Spark" every Toriphile in Leno's audience screams, "I love you Tori!" Beaming, she clutches her hands and tells them she loves them too.

AFTERWARD, ABOUT fifteen fans wait outside the NBC gate on Bob Hope Drive for Tori's limousine to pass. Many other have already left, having been told that Tori is unlikely to stop for them.

Boys love her, girls love her too, of all ages, but interestingly, they are almost all white. I mention this observation to Tori after one of her shows. "A lot of Asians are coming," she says. "It's the piano. A lot of them have to take lessons too." She protests half jokingly. Then she says, defensively, "I mean, you could have said the same about the Nirvana thing too."

Although Tori grew up with a fire-dreathing Methodist background, she junked that belief for her own faith in Faeries and in the earth beneath her shoes. It's one of the most overlooked turns of events of our age - the shift, in white middle-class America, from hierarchical Christianity to individulalistic, New Age creeds which say that the magic lies all around and inside of us. There are new ways of talking about the bad stuff that happens. To some listeners, Tori's songs are just kooky, but to many who shar a similar upbringing, they feel like a kind of salvation. That's why these fans don't just love her; they believe in her. On a simpler level, "Me and a Gun" - probably the least mystical song she's ever recorded - sparked a deluge of letters from Toriphiles who recounted similar horrors. This outpouring was the inspiration behind the toll-free hot line RAINN (the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) which Tori confounded in 1994.

On Bob Hope Drive, Heather, a twenty-something mother waits with the others. Heather waits, not wanting to jostle. Then suddenly, Tori is standing right in front of her, and Heather doesn't know what to say. She holds out a letter and blurts, "Would you please read this, whenever you get a chance?"

Tori says, "Sure... sure I will."

The letter starts, "Dear Tori." In it, Heather talks about her own sexual assualt as a child, and about the priest who used to kiss her, and she talks about her discovery that a classmate of her daughter's had been abused. She commiserates with Tori about her miscarriage and wishes her the best for her marriage. She ends by saying, "Thank you for your honesty."

Heather feels that Tori's eyes are looking into her and grabbing her soul. Tori opens her arms to hug her. Heather's tears are coming fast now. She is so overcome with emotion that all she can find to say is, "You're so beautiful."

original article

[scans by Sakre Heinze]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|