|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

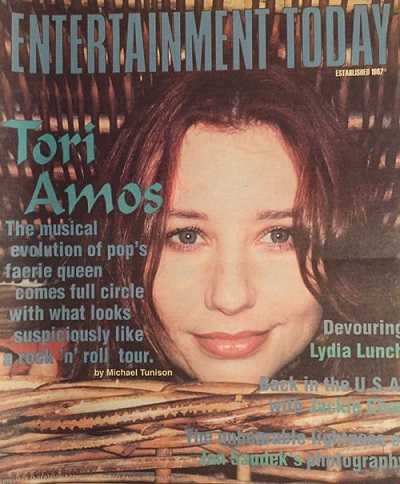

Entertainment Today (US)

September 18, 1998

Hanging with the Raisin Girls

Thinking woman's pop diva Tori Amos reinvents her sound with new songs, a new tour and -- gasp! -- a band!

by Michael Tunison

The voice on the other end of the phone is rougher than you might think, considering the angelic purity that so often characterizes it in song. Chalk the barroom-scratchy sound up to Tori Amos belting her lungs out for a Kansas City concert audience the previous evening, followed by a night's worth of travel that presently finds her somewhere called Norman, Oklahoma.

Amos will give the voice another workout at a show tonight, but at the moment she's using it to tell an interviewer about her current national tour, the first in which she's traveling with a full band. For most pop stars, jamming with a guitar, bass and drums behind her wouldn't rate as anything unusual, but -- on the off chance that the reader hasn't picked up on the fact -- Amos doesn't have much in common with most pop stars. A spectacularly gifted singer-songwriter of the let's-pretend-this-stage-is-my-bedroom school, she's best known for pouring out her emotions at her piano, either alone onstage or in the middle of her intricately layered studio recordings. When she toured behind her hit Boys for Pele album two years ago, the shows were essentially solo affairs, with her keyboards backed only by synthesized sampling or a single multi-instrumentalist sideman.

Amos began shaking up that formula when she recorded her new From the Choirgirl Hotel collection, laying down initial tracks live with a drummer, then building some of her most straightforward rock arrangements to date on top of them. The result is a fuller, harder-edged expansion of her style that successfully translates the meticulous craftsmanship of her songs into what often sounds suspiciously like a rock-band setting. The new dynamic has helped her take the live show in a new direction as well.

"It's very different," she says. "And if it weren't, then I really got it wrong. I mean, if I brought a rhythm section and it didn't change things, then I really brought a gratuitous rhythm section, do you know what I'm saying? I think the show is a real stress on the primal and the primitive side of the music, and more about the rhythm. Obviously, you hope all the other elements are still there. But there's an emphasis on the rhythm that hasn't been in the other performances."

The reinvention of Amos' sound is the latest step in the artist's remarkable musical evolution. A child prodigy who ebraced music "before I could talk," she was accepted to Baltimore's Peabody Conservatory at the age of 5, and was playing in bars by the time she was a teenager. The daughter of a devout Methodist preacher, she bounced from a severe Christian upbringing in North Carolina and suburban Washington, D.C., to forming, in her early 20s, the art-rock group "Y Kant Tori Read." The breakthrough came with the release of her 1991 debut album Little Earthquakes, a haunting collection of songs that explored, among other things, the emotional scarring she suffered as a rape victim. The subsequent albums Under the Pink and Boys for Pele found her restlessly expanding the range of both her music and ecliptic, poetic lyrics.

With her elegant craftsmanship and sometimes-startling emotional honesty, Amos' songs have won devoted followings among both critics and the public. Evocative, with a tendency toward figurative, symbolic language, her lyrics sweep over listeners with rare power, yet often defy precise literal definition. Even for their writer, the meanings of the words have sometimes shifted over time.

"On every record there's at least one song that I'm trusting that it knows what it is, because I'm not really clear on it," she says. "Obviously I have my take on it, but sometimes I am aware in a strange way that I'm kind of walking blind here. It's making sense on a very basic level. But as secrets get revealed to you, as you become a better listener and you're able to be more honest about your life and what's happened and your part in it, sometimes I see that I wasn't the character that I thought I was in the song. So as the years go by, I start putting myself in different roles in the work itself."

Rearranging some of the older songs for the new band lineup also has allowed Amos to look at her music in new ways.

"It's exciting for me, because I think some of the material had arrangements that weren't really flushed out," she says. "I'm not dissing what's on tape. You can't really do that -- hindsight's always easy. But I think that there's a real camaraderie that we have as players, so we're trying things. That's why the live show is working, because a lot of the older material is getting re-looked at.

"You make a choice on a record. Now, you can always play it that way -- for the rest of your life, as some artists do. When you go and see them in concert, it's always the same. And there are some things that are pretty much like that for me. But then there are things like "The Waitress" and "Precious Things" that have a new life to them. Although there were drums on the record, the way that they're being played live isn't what's on tape."

After the recitals, barroom sets and, now, fan-packed concerts Amos has played for nearly all of her 35 years, it would be understandable if she were tempted to back off touring a bit. Yet she still describes performances as her "passion," and has no plans to let up on her exhausting tour schedule.

"When I go to the piano every night in that setting, there's just a passion that happens with the music," she says. "And a sensuality and an honest of the heart where I don't feel like I have to justify anything. It's really about some Dionysian frenzy where you can let sides of yourself that you may have judged really harshly to come to the forefront and look at them. Whether it's a side of me that can be quite violent or something that I've been taught to feel negative about, I can invite them consciously, as a part of my personality, and recognize them in myself."

The many sides of Amos' personality -- sensual and intellectual, mysterious and accessible -- all come together somehow in her trademark concert style. Equal parts Jerry Lee Lewis-life piano pounding, classical performance and cofeehouse poetry slam, her work onstage leaps from one emotional precipice to another, raising the occasional eyebrow with the open sexual energy that often characterizes it. Even the singer herself, when confronted with an old show captured on tape, occasionally feels a little uncomfortable with what she's seeing. "I think in some of the older performances, sometimes it's a bit painful to see how uncomfortable I was with my sexuality."

Over the years, the frank, open-hearted nature of her work sometimes has caused emotional confusion around her. She traces this back to the very beginning of her development as an artist.

"You know, the funny thing is at church and as a piano player, I was encouraged to be seductive at that piano. Because there were a lot of benefits for a lot of people if I were. But then I got in trouble for doing it. So I've had to really come to terms with what is sensuality in a woman. What does it mean to me and how do I want to express it without needing to justify it to anybody but myself?"

In describing the complex relationship artists share with their audiences, Amos refers to what she calls "the three stages of seduction."

"There's the one where somebody's watching you from afar and they're not in your inner world, whether you're a performer or you're a writer or whatever -- somebody sees you from afar and feels something. Then there's the place where you let somebody in your life, and it might be playful, and you're working with them, etcetera, but they're not the man that you're dragging back to your cave. Then, of course, there's the third one, which is the man you're dragging back to your cave, and it's like, 'OK, big boy, put your boots on.'"

The problem, in Amos' view, is when someone -- say, an overeager fan -- reads the arrangement differently and wants to go back to the cave, if only figuratively.

"And you're going, 'Hang on a minute,'" Amos says. "'That isn't the choive that I'm making. If I've brought up an emotion in you, we both agreed to do this. I'm aware that I'm bringing up emotion in myself, and if that brings it up in you, then we both agreed that we wanted that experience, but I'm not promising to drag any of you back to my cave. Nor do I expect you to drag me back to yours. We take this feeling, which is very Dionysian, and then we go and take it back to our life. And that's what live performance is."

Profoundly inspired herself "by a lot of musicians and writers -- particularly poets," Amos has experienced this relationship from both sides.

"When I go and see people who inspire me, then I take that inspiration back to my well and my creativity and my love and my friends. You know, I'm not waiting to get them to take me back on the bus and give me a root beer enema or something."

Tori Amos plays at Arrowhead Pond of Anaheim, Friday, Sept. 18; at the Santa Barbara Bowl, Sunday, Sept. 20; and at the Greek Theatre, Tuesday-Wednesday, Sept. 22-23.

[transcribed by jason/yessaid]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|