|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

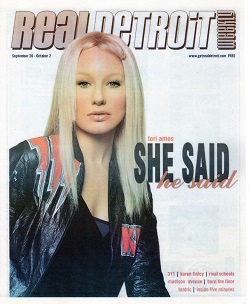

Real Detroit Weekly (US)

free local paper

September 26, 2001

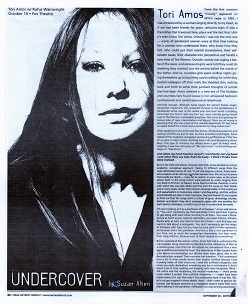

Tori Amos: Undercover

by Suzan Alteri

From the first moment "Crucify" appeared on MTV's radar in 1991, I was enraptured by a woman singing directly to my heart, as if we had been friends for years, centuries even. It was a friendship that traversed time, place and the fact that I didn't even know Tori Amos. Certainly I was not the only one -- scores of adolescent women were at that time looking for a woman who understood them, who knew how they felt, who could put their mental breakdowns, their self-esteem issues, their obstacles into perspective and herald a new time of The Woman. Outside, society was raging a battle of the sexes, and adolescent girls were told they could do anything they wanted, but the actions belied the words of the father. And so, countless girls spent endless nights giving themselves up to boys they cared nothing for while they peeled wallpaper off their walls like shedded skin, rocking back and forth to settle their jumbled thoughts of suicide and marriage. Amos ushered in a new era of The Goddess and countless fans found solace in her whispered bedroom confessionals and candid sermons of sisterhood.

Ironically enough, although Amos began the second female singer-songwriter movement, she remained immune to the protestations of threatened white men in the media who saw their world crumbling. Amos had one foot in and one foot out, never entirely giving herself over to The Womyn. It prompted questions. Was Amos just spewing fallacious tales of rape, masturbation and silence? Were we all wrong in assuming that she was a part of the celestial sisterhood? Or had Amos co-opted herself for a buck and a name like so many before her?

After speaking to the artist over the phone, all these accusations and reeling conflicts are put to rest. At once powerful and fragile, Amos talked of her husband, computers and saving girlfriends as if the two of us were in high school, drinking Coca-Cola and whispering about boys. This type of intimacy has always been a part of Amos' work, whether it was the cold quiet of "Me and a Gun" or the chilling nostalgia of "Marianne."

And when my hand touches myself / I can finally rest my head / and when they say take from his body / I think I'll take from mine instead.

But on her sixth solo album, Strange Little Girls, Amos decided on a more academic, conceptual approach. Taking 12 different songs from the male-dominated canon of rock 'n' roll and popular culture, Amos wanted to explore what men say and what women hear. She set out to prove that words are deeds -- every bit as violent, in some cases, as the actual action itself. In the songs (which were penned by artists ranging from Lou Reed to Eminem to Slayer), Amos found a female character, a voice with which she was able relate and thus turn the songs on their heads, and in many cases, render them almost unrecognizable. In this world, sex and sexualization is involuntary, violent and degrading, and the written words (deeds) are toxic in their confusion, fear and hatred. It's no surprise to find out that the songs swirl in a haze of guns, drownings, murder, division and death; they don't necessarily agree with one another, but each sparks a dialogue, a soulful tug of war to understand the sexes.

"If we're looking at it as a pantheon of archetypes," Amos said leisurely, "You can't necessarily say that everybody in the pantheon is going to get along with each other, but they're all there. You need a Persephone as much as you need an Aphrodite, you need Artemis, Athena, Psyche and, as well, you have to have Zeus there -- and that guy, you want to talk about a misogynist. You don't necessarily get the magic of Dionysus with Zeus, but you have to have both of them represented because that's the pantheon. And this is like a mini pantheon of our time, not as much the songwriters themselves, but their work, their song children, because each of them tapped into something."

But to understand the woman within, Amos first had to understand the man outside. Using what she has described as the Laboratory of Men as a control group, men from her life helped her comprehend how a man says something and what he hears. The Laboratory of Men taught Amos a lot about communication, but did she learn more about men in the deconstruction process? That was never her intention. "I did understand how a lot of them would resolve their musical conflicts because I was crawling inside all their structures. I took the architect's blueprint, and when you really deconstruct something, you live it and breathe it. And I spent a lot of time, waking and sleeping, with their blueprints. What I did notice was the vocabulary, the musical vocabulary -- that's pretty much where it ended. Their political viewpoints -- I might have been made aware of it, but that wasn't the centerpiece here. It was like, 'OK, let's not get trapped in those details. Next.' I didn't want to get too distracted. Just because someone is a misogynist doesn't mean their work didn't belong in the pantheon. Infiltration is a way to bring awareness."

I'm not policing what you think and dream / I run into your thought from across the room / Just another trick / Can I weather this?

Artists are often caught between a world of their own making, words they've written often used against them by fans who become attached to a perceived reality (which is in fact only great storytelling), and the ever-changing world surrounding them that persecutes their creativity and forthright voice. Art and society -- inextricable from one another though the cleavage between the two can create an uncrossable rift. Our responses to art, in this case the musical form of creation, are heightened to such a degree that music often informs every aspect of our cultural upbringing. Teens make mix tapes to explain a moment in time or to share a message. For some, the words of others offer a voice or expression that they themselves don't believe they have. But since artists often speak (metaphorically) for a certain segment of the population, any intelligent debate between the art(ist) and the person is tied up in responsibility. How much are artists responsible for what they write or say? And how much are artists responsible for the impressionable adolescents who hang on their every word? When you put these questions before The Goddess, the answer is both simple and complicated.

"I think that whether you like to hear it or not, or any other artist wants to hear this or not, this is what I believe, what I'm about to say," Amos posited. "Of course I believe in the First Amendment, but as a writer I have to wake up -- my DNA is in that stuff, and I might be having a moment, like some of these artists are tapping into the unconscious rage of men against the feminine, let's say, or against being gay -- that they would have a wet dream and the image would be of another man. So some of these guys might be living that in their life, and they're tapping into other men that are living that and so they sing stuff and write stuff that plays that rage out.

"The bottom line though is when you wake up as a writer 10 years from now, you cannot separate yourself from what you've done and you're going to have to, in some way, deal with it. If anybody thinks they can get away with something they've written, you can't. Trust me.

Amos doesn't regret most of what she's written, certainly not any song that's made the final cut to one of her six albums. To her, what she writes is a document, "It's where I was and that's what I believed at the time," she said. None of which means the danger is any less perilous -- perceptions change on a dime. Not to mention the fact that certain artists (perhaps some on Strange Little Girls) are stirring it up for just a little notoriety or a quick buck.

"But do you really think they're escaping that?" Amos countered. "They might today, but your DNA is all over it, your ink prints are all over that song. I do believe that there's a responsibility to you as a writer, to your own soul, and some of us are enraged and some of us are speaking our beliefs and playing it out. I think it's all good that all this comes up, and I think a lot of artists dance around the responsibility, but I don't believe they escape it."

He says will you ever learn / You're just an empty cage girl / If you kill the bird

Amos thinks it's somewhat funny that fans believe they know her merely through her work, and while many of her songs play on personal experiences, there's always an otherworldly element involved. There's Tori Amos and then there are Tori Amos' songs, which exist in their own right. "I think as a songwriter it's a little arrogant to think you do it all by yourself -- if you believe in a creative force," she said. "And I think that there is a skill tapping into it, but it's never just you, and if you ever think it is just you, then that's where the sickness will start. That's when you start seeing people check into places. You start to split in two; you start to shatter when you think it's all you. The ego gets so puffed up that you forget you're just part of a creative force. But it doesn't mean you take any less responsibility. The muse is not getting the publishing on it," she laughed.

I need a big loan / From the girl zone

Amos' muse for Strange Little Girls came from a place far out -- not surprising considering we're dealing with Amos, a known fan of mysticism and ghosts, a woman who believes the dead can talk. The characters for each of her covers (twins in the case of "Heart of Gold") came to her with their own viewpoint on the man's words, and as part of her creative force, Amos let these females possess her to set their voices free, and some of them are still with her. "Some days I really like the neutrality of the 'Real Man' character, some days I really like 'New Age' because she's always researching something and I have this librarian fantasy anyway. But there are some days when I really like the 'Raining Blood' gal because I think that she had a certain set of circumstances to deal with that I will never know in this lifetime. And I can't imagine what she went through."

She said I've your voice / I said you don't need my voice girl / You have your own.

Suzan Alteri's DNA is all over this page. Email her at suz@getrealdetroit.com to find out what is going on with her during this moment.

Tori Amos w/ Rufus Wainwright

October 19 - Fox Theatre

original article

[scans by Sakre Heinze]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|