|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

Toronto Globe and Mail (Canada)

Saturday, February 26, 2005

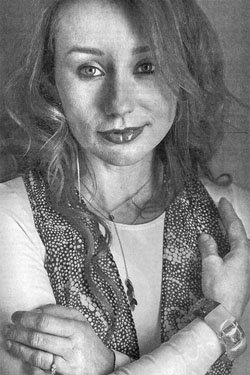

Tori Amos: Certainly weird, also shrewd

What is she talking about?

A conversation with Tori Amos makes this writer long for Britney's dumb directness.

by Sarah Hampson

"I see myself very much like a Frodo character, except with cute shoes," giggles Tori Amos. Like a little girl, she extends both feet, straight out in front of her, to show off a cream-and-black pair of Mary Janes, worn over pale fishnet stockings. "They're Kurt Geigers, bought in London on the high street," she marvels, gazing fondly at them as she turns her ankles this way and that.

That, dear reader, is one of the few moments of levity the singer-songwriter will allow. The multiple-Grammy-nominated alt-rock artist has been called a flaky moonchild; a navel-gazing kook; a thinking man's Madonna. What you implicitly do, when you interview her, is go on some kind of journey, like the one she and co-author, music journalist Ann Powers, take readers on in the recently published autobiography, Tori Amos: Piece by Piece.

It gets weirder from here, folks.

There's a wood-nymph quality to Amos, and not just because she's wearing a flimsy tunic thing over a white shirt and dark, pinstripe pants, cinched at her tiny waist with a wide leather cummerbund. The effect is sort of Wonder Woman of the Forest. Plus, she lives in a 19th-century cottage near Bude, in Cornwall, a part of southwest England moody with strange stone formations, windswept moors and myths of Merlin.

Cornwall is where her husband, Mark Hawley, a sound engineer, is from. But clearly she is more spiritually at home there than she would be in North Carolina, where she was born Myra Ellen Amos 41 years ago, the daughter of a Methodist preacher and a mother who is a Cherokee Indian. (Amos also has a residence in Ireland, and a house outside Miami.) "Christianity hasn't invaded people [in Cornwall] to the point where they have stopped looking for the pieces of their mosaic in the archetypes that exist in all mythology," she explains.

Cornwall is where her husband, Mark Hawley, a sound engineer, is from. But clearly she is more spiritually at home there than she would be in North Carolina, where she was born Myra Ellen Amos 41 years ago, the daughter of a Methodist preacher and a mother who is a Cherokee Indian. (Amos also has a residence in Ireland, and a house outside Miami.) "Christianity hasn't invaded people [in Cornwall] to the point where they have stopped looking for the pieces of their mosaic in the archetypes that exist in all mythology," she explains.

Get her going about her just-released album, The Beekeeper, and she dives into a complex world of influences: the war in Iraq; religious scholar Elaine Pagels's The Gnostic Gospels; Jungian psychologist Marian Woodman; a study of Mary Magdalene; the apiarists she came across in Cornwall. She compares her creative immersion in these thoughts to The Lord of the Rings' Frodo Baggins on his journey. "Frodo leaves his home, where it's nurturing and safe, and starts making that trek. That's how I see writing a work. You embark on something."

Maybe so. But she's left this little bee far, far, behind. I am abuzz with confusion.

"You enter the rules of The Beekeeper, and you are agreeing to co-exist within its, um..." She pauses here and tips her head forward, looking up at me with great portent. "...its matrix," she concludes.

Uh huh. Amos has always put deep feminist philosophy and personal angst into her work, so I nod my head at the queen of more-meaning-than-you-asked-for music, holding out for clarity.

On her debut album in 1992, Little Earthquakes, which sold over three million copies, she wrote a song, Me and a Gun, a story of her rape by a fan when she was 22. She had offered him a lift and was assaulted at gunpoint. (Amos later co-founded RAINN, the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network.) Boys for Pele, in 1996, was a dark rumination about men and love following the breakup of her seven-year relationship with Eric Rosse, her producer at the time. She also drew upon the suffering she had endured through three miscarriages in 1998's From the Choirgirl Hotel.

An album in 2001, Strange Little Girls, was a risky creative venture in which she interpreted songs by male songwriters, from Eminem to Neil Young. Scarlet's Walk, written following 9/11, was about "Miss America misrepresented," she tells me, researched from travelling through all 50 U.S. states.

Oh, and there was her best-of album in 2003, but could it be a simple compilation? Noooo. Its high concept was that it organized songs according to the Dewey decimal system. It was called Tales of a Librarian, and featured a new song, Angels, that, to quote one brave journalist who tried to explain it, was about "Florida's hanging chads from the 2000 presidential election as struggling seraphim trapped by earthly evildoers."

I know. Better not to ask, really. It makes you long for Britney's dumb directness.

Her best explanation of The Beekeepers goes like this: On her land in Cornwall, she has a studio in a converted barn, and every morning, she would wake up, dispatch her four-year-old daughter, Natasha, to school with her husband, listen to the BBC news and then go into the garden. There, "I started to think about power and corruption," she begins.

"And then I would think about nature. The honeybee would go to the organ of the flower," she says, using a warm storyteller-by-the-campfire voice. "It would join, propagate," she says, her hands now waving in the air as if casting a spell. "It would take the nectar, go back to the hive, not hoard it.

"Abundance," she says, eyes widening. "For the hive to exist, there has to be the belief in creation. If you create, then the other creates and the other creates, and we become abundant."

It's the model of matriarchy as opposed to the world's patriarchy, one of creativity rather than destruction. Okay. I find myself thanking her for her clarity.

Then I ask what I've been dying to know. Does she care if anyone gets the back stories of her songs?

It takes her a while to address the question. "I can't answer yet. I'm not ready," she says before launching into a labyrinthine musing on why none of us should ignore the treatment of Mary Magdalene by her sexist contemporaries. "We [women] were not allowed to be part of the prophet circle. We were always there to support," she says darkly. "And this is important. This is why we don't have women presidents." With that out of the way, and I am only quoting part of her diatribe, I repeat my question.

"Um, whether I care . . . ," she says, thinking over the issue of the album's conception. "I think if you opened up to it, it would be a great trip."

Music will often draw people in, despite what it's saying, she acknowledges. "When people are talking about elixirs and looking for that fill, whatever that is, that manna, that mystical food, that, to me, is music."

As a child she "was writing music before I could talk," she says. At 5, she enrolled in the prestigious Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Md. "I was brought up in a superachiever system as a child prodigy in which you cut off pieces of yourself," Amos says. Now, when she writes, "I allow myself to become a canvas," she says, arching her head back as if receiving instruction from the heavens. "I go completely blank and the songs take over my body and my being." Then she plays them on her piano, which she calls "a woman creature."

The Beekeeper, like Scarlet's Walk, is more political than personal, but still the inspiration came from being a woman in her 40s, she says. "I don't think it's a settling down. I think it's an explosion of chains, of preconceptions about who I am."

A New Age mystic? "I think of myself as Stone Age," she counters with a devilish smile.

Of her marriage, she says, "It's very grounding. It's a very deep commitment, which I find endlessly intriguing. We're both creative forces. He's there in every recording. I sing down the microphone knowing that he's at the other end."

Amos is weird, but in the way a richly imagined novel can be. She is not a flake, but shrewd. She knows exactly what she's doing.

As the interview ends, I ask about the infamous shot of her suckling a pig, on the cover of Boys for Pele. "Wasn't that fun?" she leans in, all girlish. "It's my Madonna and child. I was bringing in that which has been considered non-kosher back into the [Christian] fold," she explains, her face in a beautific smile.

Oh, simple old me. I thought it was about wanting a little publicity.

[scans by Candace]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|