|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

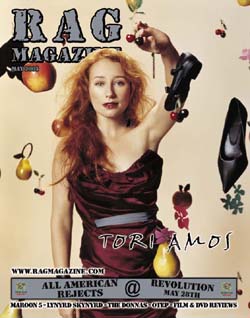

Rag (US)

Florida music magazine

May 2005

Tori Amos

On a snowy January day in New York City, a small group of undergrad journalism students frantically rush along the side walk of Avenue of the Americas. Today, they have a be hind-the-scenes tour at Rolling Stone magazine. At the end of their hour-long appointment, the students get to meet the editor. The editor looks smartly at the class and says, "Are there any questions?" No one utters a sound. Clearly, this is the moment he'd expect some brainy, over-thought inquiries. A perky, nave girl eagerly waves her hand and asks, "Why has Tori Amos never appeared on one of your covers?" The editor pauses before saying, "Uh, we will look into that." The student smiles, content with the response. That student with the "brilliant" question was me. Several months later, I stood in line at the grocery store, scanning the magazine rack, when I saw her. There she was, with her trademark fiery red locks and lipgloss mouth: Tori Amos, on the cover of Rolling Stone. I quickly snatched up the magazine. It was one of those fantastic moments of excitement when you feel like screaming with glee (but instead you actually have to check out your groceries). Somehow, I felt that I had helped to make something happen - something I felt had been important since 1992, the first time I heard Little Earthquakes. I wanted everyone to experience the honest brilliance, depth and energy that Amos delivered with her songs. Hers were stories of hope, inspiration and self-realization - things that could affect people.

Of course, I know that Amos rightfully earned that, and every other cover story on her own merit. But I felt a sense of success and happiness when I passed my fellow journo classmates, and they greeted me with smiles and congratulations. "Don't you feel like you had a part in that?" they would ask with beaming faces. Of course, I liked to hope so. Who wouldn't? But even more than any kind of personal feat, I was thrilled that Amos was finally getting major mainstream recognition. There she was - on the cover - where her artistry could not be ignored or dismissed.

That experience was seven years ago. I have had respect for other musical artists, but few have stuck around and morphed with my life's changes the same way that Amos has. Since maturity (thankfully) does kick in, I have outgrown my instant disdain for anyone who doesn't "get" Amos, and I can even understand how occasionally her ideas may seem a little too abstract or airy-faerie for some people to digest. However, bashfully, I must admit strong Amos adversaries can still make me slightly cringe inside, but I simply imagine they just haven't taken the time to understand. After all, listening to Amos without the proper foundation must be like reading George Orwell's "Animal Farm" without any clue as to the definition of symbolism. It's not that you can't enjoy the masterpiece, despite your surface understanding, but if you take the time to dive in deeper, the rewards can be endless.

"I suppose it was easier for people early in her career to label it 'freaky' so they didn't have to admit they didn't understand. But seriously, have you listened to the lyrics? Are you having trouble with them? Don't worry, so do I. But do your research." - Chelsea Laird, "Piece by Piece"

Amos approaches her craft much like a literary master writes a novel or a painter transforms a blank canvas. Metaphors abound. Words are deconstructed. Characters and themes are central. Amos' ideas are just as much fantasy and mythology, as they are history and present reality. Science, love, botany, religion, astronomy, geography, ancient ceremonies - whatever the subject - Amos closely studies her topics through expert texts and personal experience. Her songs are for thinkers. Telling someone to listen and not dissect Amos' work is like telling them to eat chocolate cake, but to ignore its rich, delicious taste.

"Music is about all of your senses, not just hearing. I think of the structure of any particular song as a house. ... Without the structure, there's nowhere for the story to live." - Conversations Between Tori and Ann, "Piece by Piece"

From Amos' elaborate album art and stylish stilettos, to her lyrical phrasing and musical composition - every artistic element is shaped with precision and a deliberate intent. One of the most conscious ways that Amos relates to audiences with her music is by paying close attention to what is happening in the world. It is important to her that she gives her listeners what they need at that particular moment in time. She blends age-old tales with current events. It's almost a history repeats itself observation, and she's suggesting that we all play roles in our lives, consciously or unconsciously, that have been played by others since the beginning of time.

On tour, the mood of the performance, the set list, is decided a few hours before every show. The songs are chosen because they tell a story. They are arranged to complement the vibe and the consciousness of the city. Amos and her manager Chelsea Laird, click away on a laptop to uncover the essence of the location, doing a quick study on its history and recent news headlines. For example, a show in Texas may get a religious tone, while a D.C. gig has a political flair. At the April 2005 performance in Orlando, Amos' mom was present, thus the selections had a maternal theme.

Though music is her livelihood, 41-year-old Amos is now equally committed to her family. On tour, she is joined by her husband/sound engineer Mark Hawley and four-year-old daughter Natashya ("Tash"). While the family has residences in Cornwall, England, and Florida, the touring routine is not viewed as something temporary and abnormal for them; it is regular life. When there is a tour, it is often extensive and involves performances on six nights of every week; but Amos has learned to build her family life and career schedule into one cohesive world. She also makes time to visit with fans in most cities. She even knows some of the regulars by name, often keeping track of the details of their lives (perhaps it's that one of their sisters is sick, or their mother just passed away).

In her first autobiography, "Piece by Piece," co-written with Ann Powers, Amos reveals intimate details of her life as a feminist, a daughter of a Methodist minister and a literary-proficient Cherokee mother, her childhood crush on Jesus Christ, obsession with Robert Plant, the struggles of being a woman in the music industry, motherhood and surviving three miscarriages, and perhaps most perplexing, her songwriting process - songs that she fondly refers to as "the girls." Amos says "the girls" know where, and when to find her. They usually arrive in unconventional ways - maybe on Jet Skis, as beams of light, or through subtle clues in a famous painter's work. They are blueprints or structures that she must enter, navigate and translate.

"This doorway has been put in place by the song itself. The structures already exist. I'm just interpreting them." - Tori Amos, "Piece by Piece"

One of Amos' intentions with her latest album, The Beekeeper, is to explore, what she calls, "marrying the two Marys." She examines the Biblical depiction of the Virgin Mary, as a wholesome, spiritual woman, and Mary Magdalene, as a profane creature of sinful sexuality. According to Amos, women have always had great difficulty merging these two aspects of their Being. It's something she thinks is a painful task and carries an unnecessary stigma. She resolves this and other dilemmas through her songs.

"I choose to fight my battles through my music, and if I'm misunderstood, well, I've done my best." - Tori Amos, "Piece by Piece"

Amos spoke with me early one morning during her Original Sinsuality (sic) tour. As was already made evident in her book, she is the kind of conversationalist who is energized, and has much to say about her work, often spinning her intricate ideas to greater heights, and phrasing her own narrative as only a true storyteller can.

I have read your book, "Piece by Piece." It provides an in-depth insight into you and your work. But it is also very inspiring and provides an optimistic feeling for readers, as far as dealing with the changes that life brings. Why, at this time in your life, did you feel it was important to write a book?

Honestly, somebody from Broadway [publishing company] contacted me. When you're presented with an opportunity like [that] (I talked to a couple of my friends who have a sense about these things.), and you get a feeling that when a window opens for you, you can stand there and think of all the possibilities. If you walk out this window, that kind of opens out into this veranda; that takes you out into God knows where; and sometimes you stay in that room and say, "Well, I don't know if I want to go out because what if it rains, or what if there's a phone call?" It's so easy to talk yourself out of things, and so I sit there and weigh out my options, but it seems like I was given an opportunity to write something. And you have to know, they don't need me to write a book about me, ya see? So I decided, why not pair up with somebody I respected, who was Ann Powers, and try and put out something that was really inspiring to people.

You talk about peeling away the "masks" in the book, and I wanted to know how writing a book is different - I suppose - from writing music, because you can put on these sorts of masks with music. How was it different for you - just being so open?

I would get up at four in the morning and write because that's when it was extremely quiet and there aren't any other opinions floating around at that time in the morning. The farmers aren't even up. So, I would look out into the blackness. There are no streetlights where we are in Cornwall. And I would try and allow myself to tap into different timeframes in my life. I sort of applied that trick - you know "A Wrinkle in Time" - where you move over part of your skirt to the other leg and you are able to shift timeframes? I loved that book as a child, "A Wrinkle in Time." And now Tash is obsessed with the movie.

Getting up that early was a discipline. But, I think it really helped me not have too many protective devices when I was writing; because, once your day gets going - I talk about it in the book - you have an image. Everybody does in order to socially co-exist. You don't sit there in writing mode at 10 in the morning while people are popping by for a cup of tea and beginning the business day at the studio. It just doesn't work like that. When we go behind the studio closed doors, it works like that again. But still, I am walking into the archetypes of the songs [in the studio]. So, I was just trying to be in my own Being writing the book.

With the latest album, The Beekeeper, what was one of the major goals or messages that you wanted to convey?

I really felt like it was essential at this time - that there was a union of sexuality and sacredness within the theme. There is so much projection of sinfulness now; especially, when you are in sort of a very right-wing dominance in some of the media. I'm not talking about people. I'm talking about ideas and ideology. Because, there are people - I'm in the Midwest right now - and I have letters coming in to me from kids coming to the show, who might be in a right-wing- Christian home; but [they] are struggling to find their own belief system. And that doesn't mean that they aren't Christian. You know Christ's teachings are not necessarily left-wing or right-wing, at all.

We choose to distort the teachings of Plato, of Mary Magdalene, of Jesus, of Buddha, of Muhammad - for our own end - for our own agendas. And you have to really be very disciplined with yourself in order not to do that. It's easy to try and hijack teachings, and then justify your own actions. [laughs] It's just what we do as people unless we say, "No, I will not allow myself to do that." And that's when you really start walking into the archetype of Sophia, the great mother of wisdom.

In Christian mythology, the Gnostic Christian mythology, and the Gnostic Jewish mythology, it is believed that God's mother is Sophia - the God that we talk about in the Old Testament - not necessarily when Jesus talks about his divine loving father - that's different than the warring God that we see. And so there are all these different archetypes, different pieces of the great creator. Do you see what I am suggesting?

And that is why I like the idea. I use the word "piece" a lot in all its form - the emphasis of war - or piece as division - or piece as, um, you know, it doesn't have to be a pejorative: p-i-e-c-e. It can be a slice of something - perfect, like an apple pie, or cherry pie - my favorite. [laughs] My point to you, though, is that these ideas are things that I wanted to put into the allegory of The Beekeeper.

The Bible is made up of many allegories and the Garden is one of them. Our story takes place, not in the Garden of Original Sin, but in the Garden of Original Sinsuality. I wanted to try and harness the words that I felt have also been harnessed by other factions that are using it to promote, I feel, distortions and not necessarily freedom or democracy or peace in any way, shape or form. But, I feel like some of these ideas have been utilized very cleverly. So, I wanted to put a different angle of the camera on them. And I work a lot in frames - picture frames. Well, the bees also work within frames, as you know, within the hives - especially in modern beekeeping, in the framing. So, I was working off a lot of word associations.

The bee has always represented an ancient feminine mystery, sacred sexuality. And, if there is one thing that I have gotten in my letters [from fans] over the years - this is what I read the most - which is the division of women from their sexual self and their spiritual self. And in the religions, they do not talk about women unifying these into wholeness and that sexuality can become sacred. You're either the mistress or you're the mother. You can't be the mother and the hot mistress all within the same Being - if you look at these different archetypes. And it's essential that women feel that they can do this.

I talk about it in the book by marrying the Marys [Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene]. The Beekeeper is the art form that represents the marriage of these two polar opposites. They've been made to be polar opposites, whether it's in Jewish religion, Islamic religion - if you look at Asia, India, the West with Christianity - you do not see the sexuality together in its sacredness. A lot of times it's in its vulgarity. Why is there so much pornography where women are defecated in all kinds of ways? I mean it's not about women being honored for this delicious sinsuality - and that's what The Beekeeper is all about.

Tell me how you got involved with Damien Rice, and why he was a choice partner for one of your songs.

I heard it, his voice. And, I thought there needed to be a male voice on "The Power of Orange Knickers." I thought it was really, really important. Because he was Irish - I did like that other subtext - the idea of [the Irish] as a people [who] know about terrorism.

"The Power of Orange Knickers" is, at its root, about invasion - [and] whether the invasion is a terrorist - and if you kind of undress that idea for a minute, this whole context of a terrorist being a guy with a turban, or the terrorist being a guy in a uniform, depending on what part of the country you live in and what side. I wanted to really go further into the idea of a terrorist because I felt like you have to reclaim the word. In order to emancipate a word, sometimes you must undress it. So, when I looked at the word "terrorist," it seemed to come back to "invasion." And yet, all around me, I was seeing people being invaded by a divorce preceding, being invaded by a desire for someone that just took over their life, an alcoholic, any kind of addict. An invasion can be a need for sugar, or it can be a need for any kind of drug. And so, I was just fascinated by this concept of invasion and how anytime the media had a terrorist warning, that trigger was able to be pushed, that button was able to be pushed. And people would support any kind of response that the government wanted to make because it is a button that brings up fear in us. Unless, we are able to reclaim the word, and say, "Well hang on. Is this a real threat? Or, is this just another way to endorse more billions and billions of dollars into securing more oil fields when we can be putting it into education?" Because, what about the terrorism within our own country, with people not being educated? Illiteracy is invading our country.

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|