|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

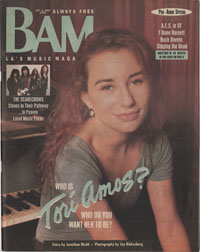

Bay Area Musician (US)

LA's Music Magazine

October 2, 1992

Who Is Tori Amos?

Who Do You Want Her To Be?

Little Earthquakes and Continuing Tremors

by Jonathan Mudd

photos by Jay Blakesberg

Tori Amos is straddling the corner of her piano stool, straddling it hard, and shaking her burnt-orange curls loose from a ponytail. Her legs are splayed, and a string-thin belt dangles between them, from the waist of her bunnched Levis to the floor of the stage. She fingers and pounds the grand piano with show-off precision, but the way she's sitting, nearly full-faced to her audience, her playing seems a trifle, an afterthought.

Beneath the falling tangle of hair, ringlets now sticky with sweat, Amos smiles. Not a smile of joy, mind you, but of something else: ecstasy, agony, both.

"Look, I'm standing naked before you," she tells San Francisco's Palace of Fine Arts, "don't you want more than my sex?" Amos's voice takes flight, a bird-song, twittering along the top of her alto range, soaring through cloudless melodies, dive-bombing into the throaty underbrush. Some lines are spoken, others shieked, sobbed, breathed. "My scream got lost in a paper cup," she sings. "You think there's a heaven where some screams have gone?"

On the keyboard, Amos is madness, all tickles and fists and tempo shifts, stops and starts and 9-month-long pauses. Bursts of Bartok clash with meaty Elton John chord progressions. A slurring bit of Rickie Lee Jones rubs against a Gershwin flourish, then slams headlong into a punkish chunk of Axl Rose. It's a bizazarre collage, to be sure. You can hear what you want to hear.

Amos' San Francisco audience must be hearing things differently. There are black-clothes artist types, rock 'n' rollers with maximum hair, kids too young to drink, regular Joes pushing 45. Everyone's into it. College coeds, their boyfriends forgotten beside them, sit forward in their seats, lips tracing Amos's lyrics, whole beings straining to absorb what she is putting out. "He said you're really an ugly girl, but I like the way you play," reveals the singer with a slumber-party lilt, "and I did but I thanked him/Can you believe that?/Sick." The coeds nod and smile tenderly at the confession.

Off on another plane, the boyfriends -- as well as the scattered stags -- sit still and listen, unsure, perhaps, how exactly to compute this flower-child onstage, how to react, among so many women, to Amos' sometimes-not-so-subtle stool-grinding. Particularly when it comes in a hailstorm of religious references - to saints, sinners, saviors, and sacrifices. "I want to smash the faces of those beautiful boys," she sneers, landing on a jarring chord, "thos Christian boys/So you can make me cum/That doesn't make you Jesus." The men shift in their chairs.

Elsewhere, there are women with women, and, shoulder to shoulder, they seem to perceive every word and movement from Amos as public affirmation of their sexuality. They shout her name out loud, they applaud triumphantly, and they sit in stony silence as she huushes the hall with a trembling a capella account of rape: "It was me and a gun and a man on my back/And I sang 'holy, holy' as he buttoned down his pants."

Who is this Tori Amos? A feminist? A folkie? A rocker? A poet? A priestess? A slut?

For better or worse, she's probably all these things...and none of them. She's a 29-year-old, North Carolina-born singer/songwriter whose "second debut" on Atlantic, Little Earthquakes, has sneakily sold 700,000 units worldwide, and whose current U.S. tour is leaving a strangely disparate horse of zealots in its wake. She is an ambitious composer, an inspiring performer, and, because she has found a way to tap into her subconscious and make it everybody's soundtrack, she is an artist to reckon with,

Who is Tori Amos? Perhaps the answer is best stated as a question: Who do you want Tori Amos to be?

"I have so many sides that don't know how to make it on their own," says the singer softly. "I'm trying to bring them all together." Amos is speaking from her hotel room in Mobile, Alabama, where she will begin the final, autumn leg of her Little Earthquakes tour. There is something comfortable and Southern in her voice -- not quite a drawl -- that says she likes where she is, and that she's looking forward to this swing through the South, he old stomping grounds.

"I have so many sides that don't know how to make it on their own," says the singer softly. "I'm trying to bring them all together." Amos is speaking from her hotel room in Mobile, Alabama, where she will begin the final, autumn leg of her Little Earthquakes tour. There is something comfortable and Southern in her voice -- not quite a drawl -- that says she likes where she is, and that she's looking forward to this swing through the South, he old stomping grounds.

Yes, Amos lives in London now, and has spent most of the last decade in Los Angeles, but growing up she split her time between Newton, NC, and Washington, D.C., and she's quick to point out that those places still feel like home. "There was a real creative side that I feel was nourished down here," she says. "And believe it or now, I feel more akin to NC than up north. I mean, I'd hang out with the June bugs. And the biscuits every morning -- biscuits and Karo syrup."

Amos will play biscuit country in the next few days, and the nation's capital, too. And as much as these gigs might feel like homecomings, there is a sense that they will be difficult for her, as well. For if indeed Tori Amos is trying to bring together her many sides, this is where it could get dicey. Little Earthquakes is about facing up to your past and understanding where it is you come from. And it's a record fraught with pain. Having moved far away from the South, having exorcised its demons and discovered pop music success by parading her childhood ghosts down Main Street, Amos could quite conceivably view this homecoming party as one worth blowing off.

The biscuits provide a key. It is in Amos's most notorious song, "Me and a Gun," that the breakfast breads come up, part of a lyrical zinger that strikes at the very heart of the artist's work. "Do you know Carolina?" Amos sings plaintively, as in a hymn or plantation work song, "where the biscuits are soft and sweet/These things go through your head when there's a man on your back and you're pushed flat on your stomach/It's not a classic Cadillac."

This is no rhyming, radio-ready hit single about bad girls and automobiles. This is rape, and Amos does not dress it up for us. Nor does she shy away from the truth inside her subconscious -- however odd or misplaced. "Biscuits" follow violation. "A slinky red thing" adorns "Holy, Holy." "Jesus" hangs with "Mr. Ed." "Me and a Gun" is laced with such juxtaposition, such commingling of honesty and imagination, and it has frozen listeners.

Surely they're frozen rock-solid back in Newton. The welcome-home show in North Carolina must loom more like a return to the scene of the crime. "I'm talking about my true feelings," says Amos. "The truth is a very powerful thing -- and a very scary thing."

The women's press discovered the power of Tori Amos's truthfulness as early as anyone in America. Soon after the release of Little Earthquakes, features began to appear in such unlikely magazines as Glamour and Vogue, often with the lyrics to "Me and a Gun" printed alongside. When Amos revealed to an interviewer that the film Thelma and Louise had given her the courage to confront her own nightmare, the women's movement latched onto a new hero.

As it happens, though, Amos's popularity has hardly been limited to feminists, lesbians, and women who have been misused. Few people -- make or female -- can watch the rape scene in Thelma and Louise, or any part of Jodie Foster's The Accused, without feeling their guts rise and their throats catch. And experience with "Me and a Gun" is just the same. Women may have made us listen to the song, but now we're all turning up the volume. Now we're all coming out.

And we're checking out the rest of Little Earthquakes, too. Like "Me and a Gun," it's an intensely personal record, and like Amos' stage personality, it's quite impossible to categorize. There are big production numbers -- songs like "Girl" and the title track -- that are wet with strings, synths, and background vocals, deep with thudding kick-drums and grating guitars. They bring to mind the sophisticated pop of Kate Bush, except that Amos's use of Eastern harmony and trick rhythms is not so self-conscious, and her voice not so tiresomely operatic.

There are piano songs -- "Winter" and "Silent All These Years" -- that derive their power from wide openness, from the nearness of Amos's quivering falsetto, from syrupy orchestral swells. "Leather" offers more disquieting juxtaposition, as a swaggering, burlesque piano line is busted by a chorus of angelic harmonies and the singer's faint plea to God. Amos's tone on "Tear In Your Hand" somehow manages to recall Sinead O'Connor and Stevie Nicks, but minus the pretentiousness. And surely neither of those artists has ever tried to tackle a vocal line so demanding.

Little Earthquakes has its uncertain moments -- some of the arrangements wander where they could dash home, for instance -- but for the most part, it's a smashing effort, and it holds something for everybody. Of course, stylistic variety alone does not a successful record make. Tori Amos' stories are the album's knockout punch. Delivered with conversational intimacy and mixed up-close, they're like entries in a long-guarded diary. Open the scribbled-in little book, and a world tumbles out -- a world, it would seem, that Tori Amos had no idea was hers.

Born Myra Ellen 29 years ago in the mill town belt of central North Carolina, Amos is the daughter of a Methodist minister and his wide -- "discipline people," she calls them. She attended a school taught by nuns, sang in the church choir, and, by the wise old age of 5, had learned her way around the piano well enough to win a scholarship to the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. Though she returned to North Carolina for her childhood summers, Amos' school years were spent in Peabody's rehearsal rooms, where her little fingers were taught to play Beethoven, Chopin, and Debussy.

Despite the presence in her life of strict religious doctrine, there was something of the rebel in Amos from the get-go. She was booted from Peabody at the age of 11 for hearing the drums of improvisation louder than the black and white keys of ritual, and by 13 she was hitting the piano bars of Washington, D.C. -- as a virgin-daquiri-drinking nightclub performer. The Rev. Amos chaperoned his daughter to the gigs for a while, but when she entered high school, he began to lose her. "It was a pivotal time," she remembers. "I mean, I was ready to go run away and follow my friends who were running away."

Finally, at 21, Amos did run off -- to LA and a shot at music business. She hung out, met musicians, joined bands, and cranked out flavor-of-the-month demo tapes: hard rock, soft rock, techno, dance, whatever. Amos wasn't getting anywhere -- the major labels repeatedly rejected her stuff -- but she was having fun. "It was like being in a candy shop," she says of her first year in LA, "and not being afraid of getting a cavity. I answered to no one."

For a while, at least. By age 24, she was do-anything desperate, and she started answering to the music industry. Atlantic Records saw something in her 1988 incarnation, a hard-edged outfit called Y Kant Tori Read (featuring Amos on synthesizers and Matt Sorum, later of the Cult and Guns N' Roses, on drums), and signed her to a deal. She had hair, she had leather, she had thigh-high boots. "My vibe was a metal chick," laughs Amos. "That was my look and that was my attitude."

It was also her death. Y Kant Tori Read was stillborn, as the industrty likes to say; it never charted, not even low. All of a sudden, Amos's candy shop was closed.

"When the album bombed, I was like jelly on the kitchen floor," she says. "I don't just say this in interviews, either: I sat on the kitchen floor counting the specks in the linoleum, crawling to the bathroom and back again. For like a month."

As it turned out, it was the month that would determine the course not only of Amos's career, but of her life. When a friend (Sin [Cindy Marble], of the then-hot LA band Rugburns -- how's that for allegory?) coaxed her out of the apartment for a visit one evening, the haggard Amos stumbled into her future.

"Sin had this old piano," she says, a certain spookiness in her tone, "and I just started playing for the first time in I don't know how long. Sin sat in the corner with all the lights out, so that I almost forgot anyone was there, and five hours later, as I was winding down, she came up to me and said, 'Tori, you have to do this now.' And I said, 'What if I get ripped to shreds?' And she said, 'Yeah, but you've just been ripped to shreds being something you aren't. Why not get ripped to shreds and have some self-respect?'"

Sin's words became Amos's call to arms. The next morning, she had a rented piano delivered to the house, and she made a pact with herself to sit at it 15 minutes a day. "I'd just be honest," she remembers, "for the first time in my life. Instead of making excuses and justifying everything and having the walls up. And that's how the songs started to come out."

Slowly, and with the blessings of an unusually patient record company, the groundwork for Little Earthquakes was laid. It was an excrutiating time for Amos, an anguish-filled therapy session conducted on the piano keys. "Up until then, I hadn't looked at the truth in my life," she says. "I wouldn't look at growing up as a minister's daughter and how resentful I was toward the institution, that I felt like it was abusive. And I always felt guilty for thinking that. I always felt blasphemous."

Recognizing the guilt -- every churchgoer's cross to bear -- was the big step for Amos. From there she could approach her family, her fears, her relationship with the opposite sex. "I'm still fighting to this day to get over some very serious guilt," she insists. "Just guilt for loving, guilt for having passion. I think a lot of people -- not just women -- will understand what I mean. I think women have more experience with it, though; you see, the Virgin Mary was put in our face so many times as our female role model."

Clearly, just such a realization provided the seeds for "Precious Things" and the stunning "Crucify": "I've been looking for a savior beneath these dirty sheets/I've been raising up my hands/Drive another nail in."

"How do you fight this idea that you can't have sex and also have love?" Amos asks. "How can you be a lusting, wild creature and be a mother? Well, I believe you can have both." And her tone turns deadly serious. "I've been fighting practically my whole life to get where I am and change the way I think. It's one thing to say, 'Yeah, yeah, yeah -- I recognize it,' and it's another thing to start really feeling it."

Amos' self-awareness sounds so natural, so practiced, it's easy to forget that it's actually quite new to her -- that just four years ago, as the lead singer of hair-band, she was anything but herself. What would she be doing if Y Kant Tori Read hadn't stiffed? "Still doing it," she says. "That's why that record is the biggest gift in my life. More than [Little Earthquakes]. It was my bomb to blow up the world. Without it, I wouldn't be the person I am. I had to be publicly humiliated before I was willing to look. And talk."

"Silent All These Years," therefore, is an apt title for Tori Amos's breakout song, the one that convinced Atlantic that their reinvented artist was ready to meet the world. "Sometimes I hear my voice and it's been here -- silent all these years," sings a somewhat surprised-sounding Amos, a disjointed piano figure sprouting up beside her. It's a moment of self-discovery, of new life, and it provided a perfect centerpiece for Little Earthquakes.

With "Silent All These Years" in the can, and a buzz on the record growing at Atlantic, manager Arthur Spivak and label exec Doug Morris decided on a game plan. They moved Amos to London, booked her in some pubs, and let the word move through the streets. The strategy paid off. By the time Atlantic U.K. released "Silent All These Years" as a single and a video in early 1991, Amos had a solid core of British fans. The tune charted -- surprising for such pop unorthodoxy -- but, more importantly, it got the music press rolling. When Little Earthquakes his stores in America, Amos was already a critical and commercial sensation abroad. It made coming to America a breeze.

Amos has been on the road for nearly a year now -- longer if you cound her 1991 trips to Germany, Australia, Korea, and points in between. It's just her and a grand piano in these mid-size halls, and wherever she goes, she packs them in. Audiences get an intimate but animated version of Little Earthquakes in concert, plus some odd covers: Led Zeppelin's "Whole Lotta Love" and Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit."

Nirvana? Yes, indeed, and it works. Atlantic Records liked the cut so much they included it on Crucify, the recently released EP of covers and remixes that even American radio understands. The Stones' "Angie" is also on there, and a shimmering treatment of Page and Plant's "Thank You" that's well worth the pricec of admission.

If Amos's rock 'n' roll dabbling seems a mite out of character, listen to this: "I saw Pearl Jam play the other night, and I haven't been that inspired in a long time, to be honest with you. I've been getting tired lately, and they lit a spark in me again -- a memory of why I'm doing what I'm doing, why I chose to be up there alone with the piano. It's to have that kind of intensity, but in my way. I didn't get the chance to thank them."

Does that mean there's a Pearl Jam cover in Tori Amos's future? The singer just laughs, not to deny it, but to let us know that anything is possible from here on out.

When the Little Earthquakes tour ends in December, Amos will take a sabbatical in the American Southwest. Having played six nights a week for a year now ("like Metallica," laughs her manager), she should feel entitled. "I'm going to the desert to rest and recuperate," she says. "I just need to sleep and not think about music for a while."

But when she wakes, there will be a lot on her mind. "I know that almost anything I do is probably going to get ripped to shreds," she predicts. "It'll really be under the microscope." To be sure, critics and fans alike will want to see if Amos can match the intensity of Little Earthquakes, if she can live up to her promise, if she can stick to her creed of self-awareness in the face of gold-record success. "I know that people don't want to believe that something can really last," she sighs. "Because if it doesn't last in themselves, then they can go, 'Yeah, well, she didn't last and they didn't last and he didn't last, so it's OK if I don't.' Well, it's OK if you don't, anyway. You see, we like other things to fail because taht justifies failing for ourselves."

"I have to do the next record completely for my own excitement," Amos says, her thoughts coming fast. "I have to challenge myself and get off on the challenge. I can't write Little Earthquakes again, you know. I can't write 'Silent' again; I'm not silent anymore. I can't write 'Me and a Gun'; my God -- I've written that. This record was me coming from a completely unconscious place. You have watched me open the first door -- well, that's always the most exciting. That's like the first six months with your love. It will never be the same. Never."

And there Tori Amos pauses to take a deep breath. It's as if she's gathering strength for a crucial step. "So I'm a little afraid," she says. "And I just have to accept that I won't be your new love anymore."

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|