|

songs | interviews | photos | tours | boots | press releases | timeline

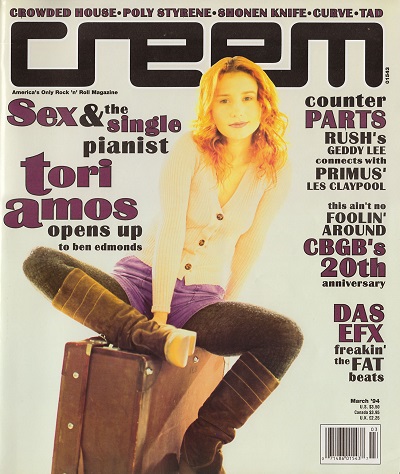

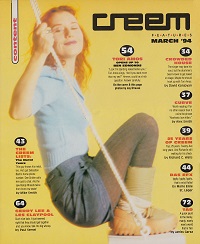

Creem (US)

March 1994

Sex & the single pianist

tori amos opens up to ben edmonds

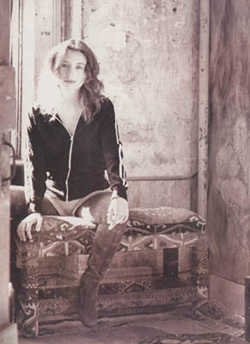

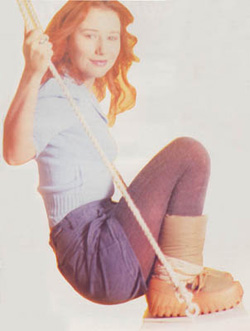

photography by Jay Strauss

I Believe In Peace, Bitch. Tori Amos Talks Back

Everybody is multi-lingual

You learn a language to communicate with other people. You learn a dream

language to communicate with yourself. But the real language, the one

that best communicates your essential nature and its relationship to the

world around you, is one you don't learn.

You find it.

You find it in the feel of a brush on canvas, the purr of a finely-tuned

automobile engine, the perfect flush of an unclogged toilet, or the

hammered keyboard of an old upright piano key. And when you do, you're

found not only your voice but something worth saying with it.

From the time Tori Amos was first able to physically negotiate the

height of the piano stool - when her age was being measured in months

rather than years - her fingers knew where to go to continue the musical

copiano stool - when her age was being measured in months rather than

years - her fingers knew where to go to continue the musical

conversation taking place in her head. The amazement generated by her

replications of complex pieces of music she'

From the time Tori Amos was first able to physically negotiate the

height of the piano stool - when her age was being measured in months

rather than years - her fingers knew where to go to continue the musical

copiano stool - when her age was being measured in months rather than

years - her fingers knew where to go to continue the musical

conversation taking place in her head. The amazement generated by her

replications of complex pieces of music she'

Tori thinks this might have something to do with past lives. I think

it's more that music picked her and simply decided not to wait till

junior year of college to let her in on it.

This is the tongue you truly communciate in. An action language, it

arouses in significant others the recognition that they somehow share

your private emotional Esperanto. They get it.

Diane saw the video of "Silent All These Years" on MTV one night, and

her connection with it was immediate and complete. To use an exhausted

but unavoidable cliche: Diane felt that Tori Amos was speaking directly

to her. The next morning she called record stores until she located a

copy of the Little Earthquakes album. She got off work at five o'clock;

by 5:20 it was hers.

All this was triggered by a single exposure to the song and video. One!

I'm told that this phenomenen is not at all uncommon among Tori Amos

fans. If it wasn't so obviously wonderful, it could almost be creepy.

My girlfriend Diane discovered Tori at a time when she had quite

suddenly become not my girlfriend. Little Earthquakes became her closest

companion through the months we weren't together. To condense a very

long story, she found a way to expose me to the record. I responded to

it almost as intensely as she had, and Little Earthquakes became our

bridge back to each other.

A cute story, but what's most interesting about it is that, while we are

bonded by our shared passion for this piece of music, the way we

perceive it is completely different. To me, it's the album that brought

us back together, but to Diane, it's the album that held her together

when we were no longer were. These are two records that only happen to

contain the same music. (And I suspect that her Little Earthquakes may

contain some uncomfortable truths about me that I've yet to fully face

up to.)

Bare Bones

Tori Amos. Born August 22, 1963 in North Carolina. Father a Methodist

minister, mother part Cherokee. Playing piano by ear at age two. At five

wins a scholarship to the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, is kicked

out at 11 for having too many ideas of her own. From 13 on, plays gay

bars and cocktail lounges in the Washington, D.C. area. Signs with

Atlantic Records, moves to Los Angeles. Hairspray band Y Kant Tori Read,

a creative running away from home of sorts, releases 1988 album that is

met with mass indifference. Composes and records most of the song cycle

that will become the Little Earthquakes album, moves to London. Brits go

wild for her quirky, confessional songs and stark, sensuous live

performances. Kate Bush, Joni Mitchell, Patti Smith, Marianne Faithfull,

and Shirley MacLaine comparisons abound. Early 1992: LE hits U.K. Top

10. In America, becomes one of those rare albums that, with only minimal

radio and MTV support, creates its own audience. LE goes gold in U.S.

and sells 1-1/2 million around the world. Early 1994: Released highly

anticipated follow-up Under The Pink. Most of us are still digesting LE,

which continues to sell briskly. She makes the cover of Creem.

Tori Amos. Born August 22, 1963 in North Carolina. Father a Methodist

minister, mother part Cherokee. Playing piano by ear at age two. At five

wins a scholarship to the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, is kicked

out at 11 for having too many ideas of her own. From 13 on, plays gay

bars and cocktail lounges in the Washington, D.C. area. Signs with

Atlantic Records, moves to Los Angeles. Hairspray band Y Kant Tori Read,

a creative running away from home of sorts, releases 1988 album that is

met with mass indifference. Composes and records most of the song cycle

that will become the Little Earthquakes album, moves to London. Brits go

wild for her quirky, confessional songs and stark, sensuous live

performances. Kate Bush, Joni Mitchell, Patti Smith, Marianne Faithfull,

and Shirley MacLaine comparisons abound. Early 1992: LE hits U.K. Top

10. In America, becomes one of those rare albums that, with only minimal

radio and MTV support, creates its own audience. LE goes gold in U.S.

and sells 1-1/2 million around the world. Early 1994: Released highly

anticipated follow-up Under The Pink. Most of us are still digesting LE,

which continues to sell briskly. She makes the cover of Creem.

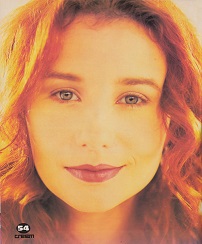

The "Silent All These Years" video showed up at number 98 on the Rolling

Stone top 100 videos of all time. When the dust finally settles, it will

place higher than that. It is a superb film. It tells you everything

about the new artist and makes you want to know more. For its audience,

seeing "Silent" on MTV was the '90s equivalent of "Like a Rolling Stone"

or "Satisfaction" on AM radio in 1965.

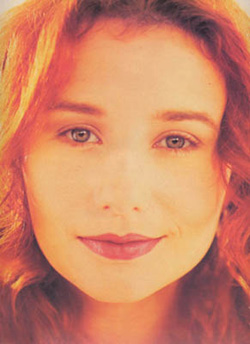

The defining moment comes at the very end of the clip, and it's one that

you don't even catch the first time through. She's been lip-synching the

lyrics but they freeze on a full frame of her face for the song's final

instrumental passage.

Or so it seems, because the frame isn't totally frozen. As the final

string unwinds, she's unfrozen for a milli-second twice, letting a

whisper of a smile play across her mouth. There's a whole other universe

in that crooked curl of the lip, a little post-modern Mona Lisa. Except

that where Mona's smile indicated a secret kept, Tori's promises a

secret to be shared.

Me and Neil Hangin' Out With the Dream Queen

"I think she's absolutely magic."

Neil Gaiman knows a bit about magic. The Englishman is the author of The

Sandman, a monthly graphic series that is among the most successful -

and fanatically followed - titles in the history of DC Comics. He also

writes novels, film scripts, and is involved in projects with Alice

Cooper and Lou Reed that you'll be hearing more about.

He also turned up as a character in a song by a certain red-headed

Sandman reader.

"Whenever I do signings," he tells me, "people give me presents. I get a

lot of tapes. Most of the demos are awful. When you're handed the

umpteenth Scandinavian death-rock tape - four Swedes gloomily

accompanying themselves on bass and harmonium, going [sings in mock

Sweedish accent] 'Morpheooos, Lort uff dreams! Comm down frum the

heavoons!' - your enthusiasm tends to wane.

"Occasionally there are pleasant surprises. At the San Diego comic

convention in '91, I was given a tape and told I was mentioned in one of

the songs. There was just a slip of paper with this name I'd never

heard, Tori Amos, and an address. When I finally got around listening to

it three weeks later, I was gobsmacked, a colloquial English expression

denoting amazement. It was stunning and terrific and wonderful. I

immediately sat down and wrote her a fan letter."

Not surprisingly, considering their creative similarities, a genuine

friendship has developed. Tori contributed an introduction to Neil's

recently-published hardcover edition of Death: The High Cost of Living.

Bits of Amos lyrics - Neil quite cheerfully admits, whole clumps of her

dialogue - have been known to creep into The Sandman. Some claim that

the Sandman character Delirium has evolved a more-than-passing

resemblance to the singer.

"As a live performer she's stunning." Neil marvels. "I mean she sits

there and she fucks the piano stool!"

Wondering where her performace style comes from, I tell him that I'm not

sure I can imagine five-year-old piano prodigy Tori humping her way

through Bartok at the Peabody Conservatory.

"Terrifyingly enough, I can," he laughs. "One of the things that's most

delightful about her is the wonderful combination of the precocious

five-year-old and the fucking the piano stool.

"The show that sticks in my memory was her first big concert in London

when Little Earthquakes came out. Halfway through the set a drunk

started acting up in the audience. 'Show us yer legs' and that kind of

stuff.

"She just stopped playing, turned around and focused on the guy in the

audience. She smiled and said 'What's your name?' He grumbled something

and she said, 'You have to understand, I've been playing cocktail piano

for 15 years. I deal with guys like you every night.' At which point the

rest of the audience were ready to take the guy out and hang him if she

so much as gave the word. But she just smiled at him. 'This song's for

you,' she said, and went into 'Leather.'"

"Look, I'm standing naked before you

Don't you want more than my sex?"

"It was the most elegant handling of a heckler I've ever seen.

"To create anything approaching real art, there's a certain amount of

nakedness involved. The willingness to bare more of your soul than is

comfortable for you or the audience. She allows herself to say things

that most people wouldn't dare say."

Diane is hovering.

"I'm not going to hover," she announces anxiously. "Aren't you excited

to be talking to her," she asks, betraying her limited exposure to rock

stars.

"Not really," I confess. "What's exciting is the way I connect with her

music. I don't need to know anything more. In most cases, you don't want

to know more than that, believe me," I add, betraying my over-exposure

to rock stars.

Diane looks at me as if I'm from the 12th moon of Pluto.

"Okay," I say, "how about if you do the interview?"

She immediately recoils from the suggestion. "No way, what am I supposed

to say? 'Gee, I rilly luv yer music.' That sounds so stupid. And what's

she supposed to say? 'Gee, I'm really honored that you chose my music to

obsess over.'"

We decide to shut up and listen to the new record, before this starts to

sound any more like a bad script for Mad About You.

I needn't have worried. Tori is delightful to talk to.

"She's one of the few genuine surrealists I know," Neil Gaiman had told

me. I understand what he means. She talks to you about songs like you're

gossiping about mutual friends. She refers to her songs as the living

things she believes them to be. With most artists this would come off as

horribly pretentious. With Tori it's so unforced and natural that you

barely notice it.

Tori has an endearing conversational quirk. She begins many of her

sentences in mid-thought, like she's tripped it up from behind as it's

moving away from her. Then she realizes where she is and doubles in

mid-thought, like she's tripped it up from behind as it's moving away

from her. The she realizes where she is and doubles back for your

benefit, throwing the beginning of the thought into the middle of her

sentence, before leaping ahead to the conclusion that rolls it all up

into a verbal small package. You have n

For your convenience, we have untangled these verbal pretzels.

For your convenience, we have untangled these verbal pretzels.

CREEM: Please tell me this isn't your 147th interview today.

TORI AMOS: Yes it is, but don't worry. I'm going to focus. I took a

little break because the one right before this was so draining. The

person asked me the same question four times.

Because they weren't satisfied with the answer you gave?

I answered it, but when it came up again it was obvious they didn't hear

a thing I said. I was trying to explain the song "God," because the

question was, "I can't believe you made God a man." I said, excuse me,

have you read any history? I don't mean to insult you, but this is not

about my opinion here. This is about the institution, and I don't think

the Pope is talking to a babe with tits when he says, "Lord, Almighty

Father." Hello?

Can you tell me a little about how this new album was born?

When I had finished the last tour, "Silent" came up to me and goes,

"There's some babes that want to meet you." I said, no way, I don't want

to meet them. And she said, "Look, if you don't meet them willingly,

then you're going to have to meet them in a very unwilling way, because

these things have to get worked out." I was like, oh no...

Why did you resist it?

What's growing about if there aren't territories where you don't even

understand the language? Two years ago I wasn't able to look at my

violent side - that just wasn't part of my consciousness. But then why

am I in situations where I'm ready to throw

somebody up against the wall and rip their head off? I've been talking

all about peace and here I am wanting to kill someone.

With Little Earthquakes, did you get a lot of accumulated psychic

baggage out of the back of your closet? It sounds like an album that

wrote itself.

Yes. I was talking about stuff I hadn't looked at, in some cases, for 15

years. On that record I began to acknowledge things, but that obviously

is only the beginning of the work. The next step is, how do you apply

this to your life?

What I've begun to learn in the last year is how I've put things in

categories. I've made this a good feeling, and that a bad feeling. But

wait a minute, Tori it's not about good and bad. Violence isn't a bad

feeling, it's just violence and you have a choice on how you want to act

it out. But if you make it bad, it's like: No, don't you dare think

about this. Don't think about wanting to punch him because he humiliated

you in front of all these grown-ups. You think it's wrong to feel that

way because he's my father, or he's my teacher, or... he's God, who has

humiliated me as a woman, in a sense. Because I've been less than. I

haven't been able to be the Pope. I've been able to be the Virgin Mary

and Margaret Thatcher, and both are kinda sexless.

Mary was our role model in the Christian church, and we're talking about

a woman that was a sexless being in the teachings. I think we can both

see what that's going to do to a whole culture. Pieces get cut out so

that certain cultures can control it, and what got cut out in the

Christian church was the sexuality and the passion. The shadow side of

that was Mary Magdalene, who we've always been taught was a whore

because that's the camp I was in. But why did I have to be divided from

the two Marys? Shouldn't it be about the balance? It should be about a

wholeness, but it's about division.

There's a division of power, male and female power, and there's a

division within my own being. There's been a dishonoring of us with each

other, and us with ourselves, and women against women, and men against

men, and women against men... and that's how the song "God" got written.

The institutional God who's been ruling the universe, in the books, has

to be held accountable. I want to have a cup of tea with him and just

have a little chat.

I feel like the song is a releasing, a sharing. It's honest and loving.

And it's sensuous. It's the goddess coming forth and saying, "Come here,

baby. I think you've had a bit of a rough job, and I don't mind helping

out now." Which I think is really cute.

I've always felt uncomfortable with "Me and a Gun," Tori's unvarnished

account of enduring a kidnapping and rape that was the most celebrated

song on Little Earthquakes. It's not the subject matter that makes me

squeamish (though perhaps that in itself says something), nor is it the

song's naked acapella setting.

I've always felt uncomfortable with "Me and a Gun," Tori's unvarnished

account of enduring a kidnapping and rape that was the most celebrated

song on Little Earthquakes. It's not the subject matter that makes me

squeamish (though perhaps that in itself says something), nor is it the

song's naked acapella setting.

It has more to do with the song's high public profile. It was the lead

track on her first English release, regularly performed on television,

and a central part of her video compilation. It was also a perfect hook

for inkmongers; you could count on finding it within the first three

paragraphs of almost every article written about her.

It's not that I think the song wasn't worth any of the above, it's that

the cumulative effect of all of it was to make it emblematic of the

album and the artist. This, to my mind, sells both short. She became

"the woman who wrote that song about being raped," when the woman who

wrote that song was really only a starting point for the artist Tori

Amos has become. The song's declaration of freedom from the oppression

and guilt of that experience (implicit in the fact of its public

performance as much as in the words) is important, but not nearly as

important as what she has used that freedom to do.

"Bells for Her" is the "Me and a Gun" of Under The Pink. The difference

between the two songs is also that of the albums that contain them.

"Bells" is about the murder of an innocence as surely as the earlier

song, but it's not the kind of Big Drama that'll generate headlines in

Glamour and Women's Wear Daily. Yet, in its way, it is no less

disturbing and the cracked chiming of the piano on the new song may be

even more chilling than the dead air with which she surrounded her

acapella reading of "Me and a Gun."

And that voice! You don't just hear the words she's singing, you hear

the whole breath. So not only are the lyrics intimate, the sounds that

delivers them to your ear is intimacy itself. This gives what she's

saying the locomotion of truth, even when your rational mind tries to

tell you otherwise.

Tori Amos is not on the cover of this magazine because she wrote one

notorious song. She's there because she's turning out to be an entire

catalog.

CREEM: Much of what's been written about you talks about the child of

the church going into secular music, hardly a new story. What's

interesting to me is that if you look at black performers who come out

of the church tradition, they seem to keep their ties to the church

after they go secular, whereas white performers seem to regard it more

as something that has to be left behind, something you sever your

relationship with.

TORI AMOS: Right.

If you talk to Aretha Franklin, she'll still go sing in church. I don't

get the feeling that you would.

Not now. No. Unless they wanted me to sing "God" or "Crucify."

Is that because white religion is about what God keeps out, rather than

what embraces?

Well, look at the music in the white church. All passion has been cut

out. That's a reflection of what the teaching is - passionless. In the

black church it's passion-filled. The spirituals that came out of

African-Americans in slavery was one way they gave themselves strength.

In the white church the intention was different, the need was different.

It was about suppressing. Suppression. In the black community it was

about releasing them from oppression. That's very different.

I understand that suppression, Cotton Mather was my great-great-great-

grandfather.

Boy, he probably burned me in a past life.

I'm paying the price now. Half my family are Christian Scientists and

the other half are doctors. You can see why I'm confused.

[laughs] Yes. Both my father's parents were ordained ministers in the

Appalachian Mountains in Virginia.Appalachian Mountains in Virginia.

Both very educated, that's why they were kinda dangerous. [laughs]

Especially my grandmother, a very intelligent woman. She could interpret

a Shelly poem like nobody I've ever known. It was

Was it an interpretation you agree with?

No! Nothing I agree with. I think Grandma was looking for what I'm

looking for, which is wholeness. But her way of going about it was to

try to make other people acknowledge their sin, and take out parts of

themselves that she thought were sinful. To get to God. But what I want

to get to is every part of myself. Because god/goddess is in everything

that makes me up. And I don't believe for one minute that we can't heal

ourselves. We can. Jesus even said that.

I'd like to believe you.

Well, it's believing in you.

Exactly. That was the central question of your song "Winter," wasn't it?

Yes!

So have you answered that question satisfactorily?

Check it out. On "Winter," the father sang to me, "When you gonna make

up your mind/When you gonna love you as much as I do?" and in "Pretty

Good Year" on the new album, I sing to the boyrfriend, "What's it gonna

take till my baby's alright?" There's no self pity in the song and yet

it's a tragedy. It's a tragedy because I can't make him love himself. I

can't do it. No matter how much I beat it into him, I can't do it for

him. Funny how the tables have turned isn't it?

Can you do it for yourself?

I am doing it, and every day is a different experience. When I wrote

"Cloud on My Tongue," I was having a hard day because I put all my power

in this other person. Sometimes I feel inferior to men who have this raw

wolf energy. The concept of free expression in your life. I have it in

my work but not in my life. So when I meet these people who have it, I

want to get close to them because...

You want to suck it up for yourself?

Yes. I try and suck their energy, that's what I do.

Now you know how it feels to be a Tori Amos fan.

Oh, get off! [laughs]

But don't you think that's what people find in your music?

I feel like my music is talking about you empowering you, not you coming

to me to get empowered.

That's what you hope will happen. My experience is that it's a two stage

process. They first come to you thinking that's something you can give

them. If they really get it, they go beyond that. But a lot of them

don't.

Well... then we're all in the same boat, aren't we?

Two weeks later I talked to Tori again. She remembers Diane's name, the

name of Diane's daughter Jessica, and most of the pertinent details of

our previous conversation. I am impressed.

Little Earthquakes was predominantly about your relationships with male

figures. But this new one seems more directed toward a female energy.

Well, yes, it is, actually. And what you think is going on is not what's

going on. I'll take you into the ladies' bathroom. You can see what's

really happening. We gotta hide you, though.

We're there, dude.

There are women friends in my life and we're very supportive of each

other. It's about equality and sharing, and not about cat fights and

trying to tear each other down. There have also been women very close to

me where it's just been ferocious. And vicious. But in a sweet little

new-age way, know what I mean? Just imagine if you met Alice in

Wonderland and she smacked you in the face! It hurt me very deeply,

because I had this idea of what The Sisterhood was.

Again, it's not about good guys or bad guys. It's not about this team or

that team, although on "Cornflake Girl" there are the cornflake girls

and the raisin girls. And you know I'm a raisin girl.

Yeah, but you grew up in a box of cornflakes.

I even did the cornflake commercial. "Cornflake Girl" is about betrayal

between women. It was based on Alice Walker's Possessing the Secret of

Joy. That book hit me on so many levels, if you know what I mean. I

believe that cultural memory is passed down through the genes. Why do I

react to certain things that... hey, I just fell off the swing. What's

happening here?

Why does that smell of burning flesh seem so familiar?

Right! [laughs] In this book she describes how, in certain cultures, the

mothers sold their daughters to the butchers to have their genitalia

removed. I was overcome by this sense of betrayal. The mothers took the

daughters to have their sex removed. There is no deeper betrayal, Ben.

There's a mixed message that Mother will always protect you. There is

this mixed message that The Sisterhood is safe. I had a rough time with

the idea that "safe with your sisters" might not be true. I had this

illusion that my sisters had only the best intentions for my other

sisters. No, Ben, this is not so! The Sisterhood has been brutal to each

other.

It's just stripping away one more rope that I'm hanging on to. You know

[sings] "looking for a saviour in these dirty streets." It comes back to

how I've got to stop looking to the outside. I could try to cut away

pieces of myself to stay in the relationship, which we all know about,

whether it's a job relationship, a friend, or a lover. We make ourselves

less so that we stay there. Or the opposite. We try and make somebody

else feel less. The friendship thing doesn't get talked about much.

Because it's not usually sexual, it tends to get put off to the side.

Exactly. But a sisterhood becomes like family. You would give your life

for this person.

That's how I see your song, each album, you're building your own family.

Things get added and things get taken away, but it's all this process of

you rebuilding a family for yourself.

Yeah. You've just made me aware of that right now. I think you're right.

And it kinda gives me a bit of comfort when you say that. I am making

friends as they come out of the piano.

Tell me if I'm wrong, but my impression is that the sound of the piano

on "Bells For Her" is as important as what it's playing or what the

words are saying.

Absolutely.

It sounds to me like a corrupted lullaby. In the beginning I had

absolutely no idea what the song was about. But just the sound of that

piano began to tell me about the song.

Right! That's wonderful. It's about when I say [sings] "Can't stop

what's coming, can't stop what is on its way." It was written and

recorded exactly as you hear it. The lyrics came in that moment. It was

almost like a trance, how that song came. It just came through. I was

translating as the feeling came through my body. Spontaneous, no fixes.

I had to write the lyrics down after I sang them to see what they were.

I just try to strip myself, peel myself like an onion. At different

layers I discover stuff. I do it publicly, and if it helps to inspire

somebody else, which inspires somebody else, which inspires somebody

else... we're talking about a really exciting world here.

I've been inspired by loads of people who showed things of themselves to

me. That's the creator coming through another being. You know when you

hear something pure. Like Liz Phair. Do you know that record?

Yes. Yes. Yes.

I just heard it. I've been away in another country, what do I know? I

heard it and went "Thank you for that. I feel so much better today."

It's like this wonderful reciprocal sharing thing. It's so inspiring,

and it inspires me.

"You stole my idea about the piano."

"You stole my idea about the piano."

Diane has been upstairs transcribing the tape of my first interview with

Tori, but she's downstairs now and in my face. I tell her that I'm not

really stealing her idea, it's more that she's completing a thought for

me. She's helped me find another small piece of this puzzle I'm working

on. She's not exactly convinced, but heads back upstairs anyway. Halfway

up, something else hits her. She stops. "You're not going to steal what

I said about her breathing too, are you?"

Well, I, ah, umm...

Diane is beginning to understand what it means to live with a writer.

"They all laughed at Sonny / When they saw his leopard vest / But long after they've

passed away / Sonny's records will play." -- The Barbarians, "What the New Breed Say"

Those stirring lines in support of rebel visionary (and Atlantic Records

recording artist) Sonny Bono were recorded in 1965 by proto-garage band

the Barbarians. It was

Twenty-nine years later, the same Doug Morris is the co-chairman/co-CEO

of the Atlantic Group (it is not known whether Sonny had a hand in

getting him the gig). He is also the senior executive who has shepherded

the career of Tori Amos.

The funny thing is that there's still more than a little of that vintage

'65 vision in Doug Morris. Change "Sonny" to "Tori" and we're in 1994,

the philosophy is essentially the same, originality wins out.

"I'll be very honest with you," Morris states with no hesitation, "I

basically gave her a hard time. When she brought me Little Earthquakes,

I didn't get into it on the first listen. It was very quiet, very

introspective, and for the life of me I had no idea how we could

possibly break this artist. I was actually kind of annoyed, because it

had been a very expensive album to make.

"It's been my experience that when you encounter a unique artist, it can

take a while to get it. After listening a lot, I finally got it, thank

God. 'Winter' hooked me first, and the more I listened to it, the more I

fell in love with it.

"But while I'm slowly falling in love with it, she's sitting in her

apartment in L.A. - where all the furniture was made of this soft

plastic that would take the form of your body when you sat on it -

thinking that I don't like the record at all.

"So I called her up and said, 'I don't know how to tell you this, but

I've fallen in love with your record.' She went, 'Whaaat?' I told her

that I had also come up with an idea of how to handle it, and would she

like to move to London?"

It was a masterstroke. Europe has always been willing to give eccentric

American originals - from Josephine Baker, Willie "The Lion" Smith, and

Ornette Coleman to Jimi Hendrix and Captain Beefheart - the even break

they don't get at home. Tori was soon clasped to the normally reserved

English bosom, and success throughout Europe paved her way back to

America.

One English music weekly was ungracious enough to suggest that Tori's

singer-songwriter persona was engineered by her record label as a

corporate response to the failure of a previous rock record she'd made,

and that the success of Little Earthquakes was due to their savvy

manufacturing of "word of mouth." Putting aside for a moment the

question of why Brits feel compelled to make class warfare out of every

situation, let's talk some reality here. Word of mouth simply can't be

manufactured. If record companies could, every record they put out would

be a hit. The most you can do is try to create an atmosphere in which

that word can be passed. If the music doesn't have the power to

captivate listeners, all you'll hear back is silence.

In the case of Tori Amos, Atlantic had no other choice. Little

Earthquakes didn't lend itself to conventional marketig strategies, and

it certainly didn't fit any American radio formats.

"I'm glad this hasn't been a radio driven project," Morris tells me. "A

unique artist doesn't make records for radio. She should make records

she loves, and that the people who love her will love. It isn't the

easiest way to do it, but if you're willing to do it the hard way, it

can last forever. If you have an artist with that kind of talent, you

let them lead, and they're going to take you to places you've never been

before.

"Tori is someone you have to let fly."

I tell Allen Ginsberg, the world's greatest living poet, all about Tori

Amos.

In 1995 Ginsberg abandoned the mannered imitations of other people's

ideas that were getting him semi-nowhere. He wrote something just for

himself, tossing off lines like a fearless bebop saxophonist. It was a

private act, something Allan wrote to explain himself to himself, but

"Howl" turned out to be a poem whose brave, authentic voice spoke, and

continues to speak, to millions.

In its own way, Little Earthquakes caught a flash of that same

lightning. So I ask the 67-year old bard if he has any words of wisdom

for a young song poet who's just written her own "Howl."

"Hmmm." The Lion of Dharma strokes his trademark beard thoughtfully.

"I'd tell her to learn some form of awareness practice or meditation, so

as to maintain connection with your own mind, and to continue developing

and enriching your appreciation of your own mind. It's really just a

question of recognizing what's there already, as she did when she broke

through and wrote for herself. It's the old thing: 'Fool, said the muse,

look in thy heart and write.' And have courage -- that breakthrough marks

the beginning of the path."

That sounds pretty much like the Tori I talked to. I think our baby's

gonna be alright.

Exclusive extras from the interview posted to the CompuServe library by Chris Nadler, Editor, CREEM magazine

Ben: I never looked at the song "God" as being exclusively about the deity.

Tori: Not totally. It's about the patriarchal system. But the patriarchal

system is headed by an energy force that has very big feet. And my whole

feeling was whether my belief system now is that the Big G is sexless...um, I

don't mean that...I mean is all sex. Even the ones that are kinda girl, kinda

boy.

Ben: The church is sexless, God isn't.

Tori: Yea. Thank you. Thank you. I HAVE been doing too many interviews today.

~ ~ ~

Tori: In "Cloud on My Tongue," I put all my power in this other person. I

think that they have something that I don't have. Well, of course we all have

things the other person doesn't have as far as abilities. But we ALL have

emotion that's capable of being complete for each one of us. But you can't be

complete for me. We know this in the head, but to really apply it is another

thing. Because when you feel inferior, you feel inferior. Sometimes I feel

inferior to men who have this raw wolf energy. I just got to this recently. It

doesn't mean that I still don't, like, snake around and leak all over the

place when I'm around one of them. I kinda go "Oh, God, here it is again. What

am I gonna do?" What's happening is that I cut that part out of myself a LONG

time ago. Because I judged it to be bad, and I was afraid of it. I was afraid

I wouldn't be respected if I got in touch with that. I'm not talking strictly

about sex. That's like a form of generating that energy, but just because

you're having sex doesn't mean you're generating that energy. Do you see what

I mean? But there are other ways of trying to get to it. Like music.

Creativity tries to get you to that expression. That kundalini energy. I do it

when I'm playing but I've really had a hard time bringing it into my life. I

sit there sometimes like all the knobs have all been turned off. And I'll see

something with the knob turned on and I go "How did they do that?"

~ ~ ~

Tori: There's this power thing that's happening. I'm talking about personal

relationships for a minute. I'm talking about them with men. We'll talk about

my personal relationships with women later, because they're both very

important and I have both in my life and this record is SO affected by that.

But...I've really had to understand what I've wanted from certain men that I

pull into my life. And it's not that I want to be compassionate to them or

anything. I'm just telling you the truth. I could've told you "Of course it

is...I want to make them brownies" and all that stuff. But what I'm REALLY

after is they have a force that makes me feel better about myself when I'm

around them. It's not just because I like them; I'm kinda in awe of them.

Ben: Which is, not so oddly enough, the thing that I like about women.

Tori: Really?

Ben: It's that wholeness, isn't it?

Tori: Yeah.

Ben: Or the possibility of that wholeness.

Tori: Yes. Yes. But more than just liking this about men, I...One isn't

enough. It's not like I meet one and there's a balance and we fill in each

other's holes. I've got loads of holes, Ben!

~ ~ ~

Ben: I understand that you were classically trained, that you went to the

Peabody Conservatory when you were five. Did you get involved with classical

music because you loved it, or were you nudged in that direction because

classical is the only acceptable outlet for someone who's got the music

disease?

Tori: Well, I was playing at two. By the time I was four I could play scores

of musicals and everything up and down the piano. I auditioned at the Peabody

when I was five, but I didn't really know why I was going there except that

these people like music and I like music, so maybe we can go eat peanut butter

sandwiches together. That was the whole concept to me: We'll understand each

other and make lots of music and won't that be fun? My parents took me to the

school because they were encouraged that I had a "special gift" as some of the

parishioners would say, and that's where you took a pianist. They didn't think

about giving me a Hammond and asking me if I wanted to join the Doors. So I

guess the goal in the back of everybody else's head was that I would become a

concert pianist. But that didn't go very well.

Ben: Before you went to the Conservatory, what kind of music were you

attracted to?

Tori: I listened to the Beatles all the time. My brother's almost ten years

older than I am, so those records were coming in and out of the house. Some of

them went out REAL quick, because my father was pretty strict about certain

things. My mother had LOADS of records from the '30s, '40s, and '50s. She

worked in a record store before she married my father. From a record store to

a minister's wife, if you can imagine that. So I had access to things like

Fats Waller and Nat King Cole, George Gershwin, and Judy Garland. But I

remember hearing "Sgt. Pepper'" and just going, "I want to be in that band!"

So when my father said me, "What kind of musician do you want to be when you

grow up? Do you want to play Bach or Beethoven?" And I went over to the record

collection, pulled out "Sgt. Pepper" and said, "I want to do this!"

Ben: So was the conservatory kinda like musical boot camp?

Tori: Of course. But they know nothing about any other world than their own

world. So how do you teach musicians to be all they can be when all you're

getting is guys that have been eaten by the worms? Hey, Bartok is amazing

stuff. Learning that has given me a foundation. But so did Jimmy Page. So did

John Lennon. So did Joni Mitchell. So did Patti Smith. To really be a musician

is to keep expanding.

~ ~ ~

Tori: Some of the most interesting, growing conversations I've had, and some of the most incredible wisdom I've gotten, has been backstage from the people who've come to see me play. I've really learned a lot just by talking to them. They all have a story to tell. And most of them are really working on

consciousness; there is a commitment to the idea that the earth is going to the next stage of development. Which means asking where we're going to be in all this if we don't take some sort of action to define our responsibility as human beings? That is the crux. And there's all kinds of ways of finding that out. I just try to strip myself, peel myself, like an onion. At different layers I discover stuff. I do it publicly, and if it helps somebody else to inspire them, which inspires somebody else, which inspires somebody else...then we're talking about a really exciting world here. I've been inspired by loads of people who showed things of themselves to me.

[scans by Richard Handal]

t o r i p h o r i a

tori amos digital archive

yessaid.com

|